IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF SHELBY COUNTY,

TENNESSEE FOR THE THIRTIETH JUDICIAL

DISTRICT AT MEMPHIS

CORETTA SCOTT KING, MARTIN

LUTHER KING, III, BERNICE KING,

DEXTER SCOTT KING and YOLANDA KING,

Plaintiffs,

Vs. Case No. 97242-4 T.D.

LOYD JOWERS and OTHER UNKNOWN

CO-CONSPIRATORS,

Defendants.

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

November 29, 1999

Volume VIII

Before the Honorable James E. Swearengen,

Division 4, Judge presiding.

DANIEL, DILLINGER, DOMINSKI, RICHBERGER, WEATHERFORD

COURT REPORTERS

22nd Floor - One Commerce Square

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

(901) 529-1999

- APPEARANCES -

For the Plaintiffs:

DR. WILLIAM PEPPER

Attorney at Law

New York City, New York

For the Defendant:

MR. LEWIS GARRISON

Attorney at Law

Memphis, Tennessee

Reported by:

MS. SARA R. ROGAN

Court Reporter

Daniel, Dillinger, Dominski, Richberger & Weatherford

22nd Floor

One Commerce Square

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

WITNESS: PAGE

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 998

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1013

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1015

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1016

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1024

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1026

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1063

[FBI Report Number 302

BY MS. AKINS:.......................... 1078

FBI Report Number 302

BY MS. AKINS:.......................... 1081

]DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1086

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1099

- INDEX CONTINUED -

WITNESS: PAGE

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1101

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1110

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1110

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1111

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1120

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1123

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1143

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1148

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1155

- INDEX CONTINUED -

WITNESS: PAGE

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1167

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. GARRISON:..................... 1175

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PEPPER:....................... 1177

TRIAL EXHIBITS PAGE

Exhibit 19.......................... 1051

Exhibit 20.......................... 1054

Exhibit 21.......................... 1085

Exhibit 22.......................... 1099

Exhibit 23.......................... 1165

P R O C E E D I N G S

(Jury in at 10:15 a.m.)

THE COURT: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen.

THE JURY: Good morning.

THE COURT: It seems that everyone is all present and accounted for.

Mr. Jowers, the defendant, is still having some health problems, but we're going to proceed in his absence. And as soon as he's able, he'll return. He's still concerned about the action against him so don't take this as – don't interpret it as he's indicating he's not interested. He is, but his health is keeping him.

All right. Mr. Pepper, are you ready to proceed?

MR. PEPPER: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: All right, you may.

MR. PEPPER: Your Honor, plaintiffs call as their first witness today Mr. William Hamblin.

WILLIAM B. HAMBLIN,

having been first duly sworn, was examined

and testified as follows:

BY MR. PEPPER:

Q. Good morning, Mr. Hamblin.

A. Good morning.

Q. Thank you very much for coming here this morning. I know you haven't been well.

A. No, a little under the weather.

Q. I appreciate your making the effort to come by and be with us. Would you please state your full name and address for the record?

A. William B. Hamblin, 322 South Camilla, Apartment 302.

Q. In Memphis?

A. Right.

Q. How long have you lived in Memphis, Mr. Hamblin?

A. Oh, probably about – I came here in '63.

Q. Been here a good number of years?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And what is your present occupation?

A. I'm a part-time security guard.

Q. You're a part-time security guard?

A. Yes.

Q. In the city?

A. Yes.

Q. And prior to being a part-time security guard and taking on that position, were you – what else did you do previous to that?

A. Well, I drove a cab for many years, and I worked as a barber for approximately ten years – something like that.

Q. You were a barber for approximately ten years and you drove a cab –

A. Right, off and on.

Q. – off and on for a number of years?

A. Right.

Q. And which company did you drive the cab for?

A. I drove for Veterans and Yellow.

Q. Both of those cab companies.

A. Right.

Q. Now, in the course of your cab driving activity and your work there, did you come to know a cab driver named James McCraw?

A. Yeah, I knew him well.

Q. And did you in fact share digs or share rooms with McCraw?

A. Well, I rented him an apartment one time. I had an apartment house, and I rented him an apartment. And I lived in the same apartment building with him a couple other times.

Q. How long would you say you knew Mr. McCraw – over what period of time?

A. Oh, probably about 25 years.

Q. So you knew him over 25 years.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you know him after the date in question in this case, after the assassination Dr. Martin Luther King?

A. Yes, sir, I met him after the date.

Q. You met him afterward?

A. Yes.

Q. And you knew him for all of those years after the assassination?

A. Yeah, it was after the assassination. I drove a short time before the assassination, but I wasn't driving at

the time the assassination happened.

Q. Right. But you knew Mr. McCraw during that period?

A. Right.

Q. Did you not only know him but were you actually living with him or close to him in the same building?

A. Well, we shared the same apartment building more than three times, and he lived with me a couple of times when he would get down on his luck.

Q. When he was down on his luck?

A. Yeah. He would lay around on my couch some.

Q. All right. So it's fair to say that you were quite a close friend of Mr. McCraw's?

A. Right, right.

Q. Now, did Mr. McCraw at various times in the course of this friendship discuss the assassination of Martin Luther King with you?

A. Yeah, he did.

Q. One time or two times or –

A. Oh, several times.

Q. Several times.

A. Yeah, several times.

Q. And was he in any particular frame of mind or condition when this subject would come up?

A. He would usually be drinking when he started. I mean, you know, he would start talking about it.

Q. It was when he had been drinking?

A. Right.

Q. Did he ever volunteer any information when he had not been drinking?

A. No, he wouldn't talk about it then.

Q. Then he wouldn't talk about it?

A. No, he didn't want to hear about it then.

Q. And when he had been drinking over these many times when he spoke with you, did he tell you a particular story?

A. Yeah. He first come out with a – he showed me a story that the National Inquirer or one of those tabloids did on him, and they did a pretty good write-up.

Q. And was the story that he told you

each of these occasions the same? Was it consistent?

A. It was – the story he told was consistent all those years. He didn't vary off of it.

Q. Over how many years would he have told you this story consistently?

A. Oh, I probably heard it at least 50 times at least.

Q. For how many years?

A. Oh, now you're trying to pin me down on dates, and I'm not good at dates.

Q. Not dates, but just roughly.

A. Oh, I would say probably 15 – something like that.

Q. Over 15 years. And what was the story that he told you consistently over 15 years?

A. Well, after I got – after I read the article and found out that he knew a little something about it, I got interested in it myself. And he would talk about Raul having a drink with him and he –

Q. Did he mention – let me interrupt

you and try to focus you. Did he mention the defendant in this case, Mr. Jowers?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. Did he know Mr. Jowers well?

A. Yeah. He worked for Jowers at the time I would say. They were both working at the Southland Cab Company.

Q. They both worked with the same company?

A. Right.

Q. Did he tell you of his personal knowledge of any involvement of Mr. Jowers in the assassination of Doctor King?

A. Yeah, he said that Jowers gave him the rifle, and he took it and threw it off the Harahan bridge.

Q. He said that the defendant gave him the rifle?

A. Right.

Q. And by the rifle, do you mean the murder weapon? Is that –

A. Right, right. That's the story that he told.

Q. And he told you this same story over

the years?

A. Same story over and over. He didn't vary off of it. And in the last he came up and I think they changed it to a bullet or whatever, but I don't remember if he changed his story or not. But he...

Q. But he consistently told you he gave him the murder weapon?

A. Right.

Q. Did he say that the defendant made any admission against his own interest? Did he say he made any admission when he gave him the rifle? Did he say anything to him?

A. He said Jowers told him to get it and get it out of here now. He said that he grabbed his beer and snatched it out. He had the rifle rolled up in an oil cloth, and he leapt out the door and did away with it.

Q. And Jowers told him to get rid of it?

A. Right. That's the story that he told.

Q. Do you recall when he said that conversation took place?

A. No, I didn't. To try to pin me down

on the date, I couldn't.

Q. Right. But would it have been your understanding sometime near to the assassination itself?

A. Well, see, I came in on the picture probably about five years after the assassination.

Q. Yes. No, I'm not talking about your conversation with McCraw. I'm talking about McCraw's conversation with Jowers. Would that have been around close to the time of the assassination?

A. Yeah, that's – the way I understand, right after it happened. Right after it happened.

Q. Now, was Mr. McCraw himself fearful of being charged or indicted?

A. That's the reason they all changed their stories. Every time they – McCraw really wanted to come out with it, but he was involved in it. And he couldn't really tell the truth. That's the reason all of them changed their stories all this time. Their conscious was getting hurt, and they were in

fear of being indicted.

Q. Mr. Hamblin, did you tell anyone, in particular a landlord of yours, that McCraw knew something about this assassination?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. And was this a landlord in the premises where both you and McCraw were living?

A. We were both living at the same time, right.

Q. And what did you tell to your landlord?

A. He came by to collect the rent –

Q. Yes.

A. – and I had introduced him to McCraw.

Q. Yes.

A. And I told him he was involved in it in some way and he told us to move.

Q. He told you to move?

A. Right. In fact, he sent the police up there and harassed us. They locked McCraw up for having a knife, and we finally wound up being evicted in about a week.

Q. So you were evicted by your landlord because you told him this story?

A. Right.

Q. Mr. Hamblin, who was your landlord?

A. It was Mr. Purdy.

Q. Mr. Purdy.

A. Right.

Q. And what did Mr. Purdy do for a living?

A. Mr. Purdy was an FBI agent.

Q. So your landlord was an FBI agent?

A. Yeah. I didn't know at the time that he owned the house. I rented from someone else, but he happened to be the owner. And he just bumped in to collect the rent.

Q. But you didn't know that he was the owner before this?

A. No.

Q. And do you know where Mr. Purdy was assigned as an FBI agent?

A. Probably Memphis office, Memphis region.

Q. The Memphis office?

A. Right.

Q. And he told you to leave?

A. He told us both to move.

Q. Both to move. And did you move?

A. Yeah, about a week later we got kicked out.

Q. Now, I want to take you back, Mr. Hamblin, to 1968. What were you doing in 1968 for a living?

A. I was a barber back in '68.

Q. And where did you work as a barber?

A. Cherokee Barber Shop, 2792 Campbell.

Q. Right. And who was the proprietor, who was the owner of that barber shop?

A. Vernon Jones.

Q. Mr. Vernon Jones.

A. Right.

Q. How long did you work there as a barber?

A. Oh, I worked for Mr. Jones probably for about five years all totalled at two different places.

Q. Is Mr. Jones alive today?

A. No, Mr. Jones passed on some time ago.

Q. And were you working as a barber in that barber shop April 4th, 1968?

A. Yes, I was.

Q. And were you working there immediately following the assassination?

A. Right. I was working there when they broke the news about – oh, I'd say about 6:00 – 5:30, 6:00 – something like that.

Q. Now, did you hear Mr. Jones have a conversation with one of his long-term customers?

A. Right.

Q. Within – how soon after the assassination did this –

A. I would say, oh, probably a week or ten days.

Q. Within a week or ten days after the assassination?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And what did Mr. Jones ask this long-standing customer?

A. He asked him who did it or who do you think did it.

Q. Who do you think did it.

A. Right.

Q. Meaning who killed Martin Luther King?

A. Right.

Q. And what did this long standing customer say to him?

A. He told him that the CIA had it done.

Q. That the CIA had it done?

A. Right. That's the answer he gave him.

Q. How long had this customer been a customer of Mr. Jones in the Cherokee Barber Shop?

A. Oh, ever since I worked for him.

Q. How many years roughly would you say?

A. Oh, I'd say probably – well, I know of five anyway.

Q. At least five years?

A. Yeah, at least five – five or six at the time that I worked for him he had been coming in.

Q. People often develop close relationships with barbers and bartenders?

A. Yeah, they'll tell a barber something

they won't even tell their own psychiatrist.

Q. Was that the kind of relationship Mr. –

A. Yeah, that's the kind of relationship.

Q. – Jones had with this customer?

A. Right.

Q. Who told him the CIA had it done?

A. I mean I didn't hear the conversation myself. I asked him what he said when he left after he had told him.

Q. You asked your boss –

A. Mr. Jones what he said.

Q. Right.

A. And he told me.

Q. And that's what he told you.

A. Right.

Q. Would you tell the Court and the jury who was this long-standing customer?

A. It was Mr. Purdy, the FBI agent.

Q. The same Mr. Purdy?

A. The same Mr. Purdy.

MR. PEPPER: Mr. Hamblin, thank you very much. No further questions.

MR. GARRISON: Mr. Hamblin, wait a minute. I may have a question if you don't mind.

THE WITNESS: Oh, okay.

BY MR. GARRISON:

Q. Mr. Hamblin, Mr. McCraw was quite a heavy drinker, wasn't he?

A. Right.

Q. Alcoholic beverages pretty regular?

A. Right. In fact, he was an alcoholic.

Q. All right, sir. And I believe you said that you would have trouble believing him, didn't you?

A. Yeah. I had some trouble believing him at times, right.

Q. You knew Mr. Jowers, did you not?

A. Right. I worked for Mr. Jowers.

Q. And you never heard him say anything about any of this, did you?

A. Not really, no, huh-uh.

Q. You said Mr. McCraw would change his story from time to time when he told it?

A. Well, they was – what I mean was

changing the story, they would accuse another dead policeman.

Q. When you say they, who are they?

A. Well, they first – they've named every policeman in the graveyard. Every time they get scared, they'll name another policeman as being the murder man.

Q. Are you talking about Mr. McCraw?

A. Well, both of them.

Q. Both of them who?

A. Mr. McCraw and Jowers.

Q. I thought you said you never have talked to Mr. Jowers about this, never had anything to –

A. Well, he's made several statements.

Q. Who has? Whose made several statements?

A. Well, I talked to him – I talked to him on the cell phone about six months ago, me and Millner.

Q. Okay.

A. And he told me that he didn't do it, but somebody by the name of maybe Earl Clark or something like that did it, and he did it

or whatever.

Q. So that's been six months ago?

A. That's here recently.

Q. Did he tell you he didn't have anything to do with it?

A. That's what he said.

MR. GARRISON: That's all. Thank you.

THE COURT: All right.

BY MR. PEPPER:

Q. Mr. Hamblin, just so that we're clear, did Mr. McCraw ever change the story he told you?

A. Never changed his story. He stuck with the basic same fact – I took the gun and threw it off of the Harahan bridge.

Q. So as far as he is concerned – as far as you are concerned, the weapon –

A. As far as I'm concerned, that's what happened. I mean, you know, I believed him because he stuck to the same story.

Q. So far as you're concerned, the murder weapon is at the bottom of the

Mississippi River?

A. That's where I would – if I was going to go look for the gun today, I would go look and look at the middle river bridge because you can drive right to it. You can walk 20 feet and drop it and be back in your car in five seconds and be gone.

MR. PEPPER: Thank you, Mr. Hamblin. No further questions.

(Witness excused.)

THE COURT: Call your next witness.

MR. PEPPER: Plaintiffs call Mr. J.J. Isabel.

having been first duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

BY MR. PEPPER:

Q. Good morning, Mr. Isabel. If you have trouble hearing me, please just stop me and I'll speak louder. Thank you very much for joining us this morning.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. For the record, would you please state your full name and address?

A. My name is James Joseph Isabel, 2344 Jackson Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee. Zip 38108-3236.

Q. Thank you, Mr. Isabel. I know you haven't been well, and we do appreciate you coming here. You were deposed in this case on October 14th, and you were kind enough to answer a range of questions at that time. And I'm going to put those questions to you this morning.

A. Okay, sir.

Q. What do you do now for a living, Mr. Isabel?

A. Well, I'm retired. I'm seventy-four years old, but I am an independent courier. I pick up food like for Memphis Hardwood Flooring five days a week, and I pick up pagers, take them to get repaired and take them back to the customer. That's all I do.

Q. And what did you do previously, Mr. Isabel?

A. Starting which year?

Q. Let's just go through the range of jobs and work that you've done, if you can. Just very quickly try to summarize for us.

A. Well, in '43 I was a sailor in the Navy in a Pacific killing force, and let's see, then I got out of the Navy. I went back to CBHS and got my high school diploma. I didn't have it before I went in the service, and then I've driven trucks.

I've driven chartered buses. I worked for Firestone at one time for six months, and I worked for Vet cab, Hams – Mike down at Yellow Cab and then Airport Limousine. Hams owned Airport Limousine. I met Jowers at Yellow Cab, and Airport Limousine, they owned – Hams might have owned Airport Limousine, and they owned something else too. Oh, it went from – I think we went from Yellow Cab –

Q. But basically you've done a lot of driving?

A. Yes, yes.

Q. You drove chartered buses?

A. Right.

Q. You drove taxi cabs, limousine service?

A. Yes.

Q. That constituted the main part of your life, didn't it?

A. A lot of it.

Q. And when did you meet Mr. Jowers as you said?

A. I met Mr. Jowers at the Yellow Cab. That was probably in about seventy – around '77 I would think.

Q. So you met him when you were involved with Yellow Cab at the same time?

A. I was working at Yellow Cab with Airport Limousine and Hams might have hired Loyd to come down there and run I think the whole operation or the biggest part of it.

Q. That's around 1977?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you come to know Mr. Jowers pretty well?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. How often would you see him?

A. Oh, daily.

Q. You saw him every day?

A. Five days out of seven.

Q. So five out of the seven days in that period from 1977, you saw him?

A. Right, and sometimes over the weekends if we had a holiday or something. We would run the buses from the airport to Millington.

Q. You saw him then as well?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. So you became quite friendly with him?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you go on any chartered bus runs with Mr. Jowers?

A. Yes.

Q. How many did you take with him, do you recall? If you don't, it's all right, but roughly?

A. Out of town probably four or five, and in Memphis, a lot of them – a lot of school trips and trips.

Q. I know it's a long time ago and you've had some medical problems even since

the deposition.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. So I'm going to try to move you through your testimony. Did you go on a trip with Mr. Jowers over one St. Patrick's Day, a chartered bus trip with him?

A. Yes. Loyd and I took two bus loads of bowlers to Cleveland, Ohio, and that was St. Patrick's Day. The reason I remember it, we were drinking green beer.

Q. Do you remember what year that was?

A. Pardon?

Q. Do you remember the year? Which St. Patrick's Day?

A. That had to be '79 – '78 or '79, but I'm saying '79.

Q. Around 1979?

A. It was winter because Lake Erie was frozen over.

Q. Right. March 17th, 1979?

A. That's what I'm thinking.

Q. And that trip was to you said Cleveland?

A. Yes.

Q. In the course of that trip to Cleveland, did you share a room with Mr. Jowers?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. In a local hotel?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And did you eat with Mr. Jowers?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. Share –

A. Did I eat with him?

Q. Did you eat?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you go to dinner with him? Did you drink with him?

A. Yes.

Q. Were you together with him most of the time?

A. Except when he was driving one bus and I was driving the other one, yes, sir. We would go to the same destination, and then we'd usually meet and go and get something to eat after we took care of the people.

Q. In the course of one evening on that trip to Cleveland, did you have a discussion

with Mr. Jowers about the assassination of Martin Luther King?

A. Yeah, after we had gone and got the bowlers, we went out and ate down on the pier, a restaurant down there, and then we went back to the hotel. And I took a shower. I don't think Jowers took one then.

I took a shower, and I came out. And he was sitting on the bed, and I sat down with my back against the bathroom on the floor. And for some reason, I just said – I said, Loyd, did you drop the hammer on Martin Luther King. And he just kind of hesitated for a moment or two, and he said you think you know I did. I know what I did, but I'll never admit it or tell it in a court of law. And I said, oh, and I didn't mention it to him again after that.

Q. Did you expect that reply?

A. Maybe, yeah.

Q. And when you asked him did you drop the hammer on Martin Luther King, what were you asking him?

A. If he fired the shot that killed him.

Q. And his response again?

A. Pardon?

Q. And what was his response again to that question?

A. Oh, he said you think you know who did it, but I know who did it, but I'll never admit it or tell it in a court of law.

Q. Did you ever raise the subject with him again?

A. Huh-uh, no.

MR. PEPPER: No further questions.

BY MR. GARRISON:

Q. Mr. Isabel, you knew Mr. Jowers quite well. The two of you were on trips together, weren't you?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And this is the only time that subject ever came up was just the one time; am I correct, sir?

A. The best I remember.

Q. He never admitted to you or anyone in your presence he had anything to do with it

or knew anything about it other than this one time; am I correct, sir?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. All right. And on this time, both of you were drinking, weren't you?

A. Uh, yes.

Q. You had been drinking a little beer; am I correct, sir?

A. Well, the best way I can describe it, I can get high on two beers and I had about six. And Loyd is a pretty heavy toper. He can handle it, and I would say he would drink close to 20 beers or more.

Q. All right. Your question to him was did you drop the hammer on Dr. Martin Luther King, and that's your question?

A. Yes.

Q. He simply said you think you know who did it, but I know who did it and I'll never admit it. Is that basically what he said?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. But he never said he had anything to do with it, did he?

A. No.

Q. That's the only words he ever used –

A. Yes.

Q. – that he knew who did it? Is that right, sir?

A. Yes, sir.

MR. GARRISON: Okay. That's all. Thank you.

MR. PEPPER: Nothing.

THE COURT: All right, sir. You may stand down. You're free to leave or you can remain in the courtroom.

THE WITNESS: Thank you.

MR. PEPPER: Thank you.

(Witness excused.)

THE COURT: Next witness.

MR. PEPPER: Your Honor, plaintiffs call Mr. Jerry Ray to the stand.

having been first duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

BY MR. PEPPER:

Q. Good morning, Mr. Ray.

A. Good morning.

Q. Thank you for coming some distance to be with us today.

A. Yeah, I'm glad to come down.

Q. Would you state your full name and address for the record, please?

A. My name is Jerry William Ray, brother of the late James Earl Ray, and I live in Smart, Tennessee, 107 Short Street.

Q. Mr. Ray, you are the brother of James Earl Ray?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Would you just describe for the Court and the jury the circumstances in which you were raised and lived as children?

A. We came up real poor during the depression days. We lived out on the farm most of the time, and that's when my brothers – they had a WPA and he just barely got by until after the depression. And then my daddy got a job on the railroad, and then we were just average people then. But back during the depression, everybody had it bad – anybody who can remember back then.

Q. How many children were there in your

family?

A. There was nine all together.

Q. And where were you and James in that constellation?

A. James was the first born, and then they had a sister Marjorie and John, then I was the fourth born. We had seven years age difference.

Q. Seven years –

A. Yes.

Q. – difference between the two of you?

A. Yes.

Q. And what grade did James go to in school?

A. I'm not positive what grade. I think he went to about a year of high school I think, but I'm not positive of the grade he went to.

Q. What did he do after that?

A. He went to – he moved to Alton, Illinois. See, we lived in a little town outside of Quincy, Illinois named Ewing, Missouri, and Alton, Illinois is about 100 miles from Ewing, Missouri. And my uncle

lived in there and my grandmother lived there, and they got him a job working at the Tambery Room. He was fifteen or sixteen.

Q. And he held that job for how long?

A. He held that job – I forget how long it was until he went into the Army.

Q. And he had worked up until the time he went into the Army?

A. Yeah, he worked every day up until the time he went in the Army.

Q. What do you remember him doing after he got out of the Army?

A. I don't remember all that much because he didn't – he came there a couple times to visit my mother and my dad. We lived in Quincy, Illinois. That's where I was born, and that's where most of our relatives are from. He come once in a while, but I didn't see him that much.

Q. Mr. Ray, as you were growing up with James, did you notice any signs – obvious signs of racism or hatred of black people?

A. No. It would be strange to have any hatred because Ewing, Missouri was just a few

hundred people, and I didn't never see one black person in the town. It's just a little bitty town, and Quincy, Illinois, where I grew up, they had 42,000 people – 2,000 blacks and 40,000 whites so I never even went to school with one. See, and James didn't either so you can't hate somebody unless you something – you know, do something to you.

Q. As he got older though and as you associated with him, did you see any hostility toward black people?

A. No, he never did have no hostility toward any race – not only blacks, but Hispanics or anybody. What he tried to do is live and let live.

Q. Now, he began to get in trouble at various points in his life?

A. Yeah, after he got out of the Army.

Q. After he got out of the Army. What was the reason for that? Do you understand how –

A. No, nobody could understand that because before he went to the Army, he was a hard worker. And he went in the Army and

after he came out of the Army, he just lived the life of crime after that.

Q. How did he get involved with various types of petty crimes and small time criminals?

A. Unlike a lot of the media think, he's easily – if he makes friends with somebody, he's easily led around too, see. And I know he committed – he robbed a post office outside of Quincy, Illinois. This is back in the fifties, and this Walter Rife was his name. He's a ringleader. After he got him to rob this post office – I mean he's as guilty as Walter Rife was for doing it, but then he went on a cash spree. They stole all his money and he got arrested in Kansas City, Missouri. Then they sent him to the Leavenworth Federal Prison.

Q. But where did he meet people like Walter Rife?

A. He met him in Quincy, Illinois.

Quincy – it was a real kind of a corrupt town back in the fifties. They had a write-up in the magazines about them.

Everything was open, see – gambling, prostitution, everything. And I knew Walter Rife and I knew his brother, Lonnie Rife, and like I say, it's a small town. Only got 42,000 people in the town.

Q. Did James tend to hang out in bars?

A. Yeah, on Fifth Street in Quincy, Illinois. That's where most of the main ones was at, and then on Third Street, it was a house of prostitution – the whole Third Street. So when you go up to the tavern, most of the people you run into was pimps, ex-convicts or something like that.

Q. Well, eventually he was sentenced and he went away?

A. Yeah, he was sentenced to Leavenworth, and I think he got out in 1958 I think – '58 or '59, and he was sentenced in there – I think he did a little bit over two years in Leavenworth Federal Prison. Then he got out, and then he met up with a guy named Owens. Owens, he was an ex-convict and they did several things. They robbed a Kroger store, and then he got sent to Jefferson City

for that.

Q. Do you know where he met Mr. Owens?

A. No, I don't because I wasn't in St. Louis at that time. I don't know him.

Q. So he was sent to Jefferson City Penitentiary?

A. Yeah, for 20 – I think it was for 20 years.

Q. Now, did you visit him when he was in the penitentiary?

A. I only visited him a couple times. I didn't visit him much because I was working up in – we wrote all the time. I mean every week we exchanged letters, but when I would get down in that area, I would visit him. But I didn't get to visit him that much.

Q. Well, he eventually escaped from Jefferson City Penitentiary, didn't he?

A. Yes.

Q. He escaped in April of 1967?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you see him after he escaped from prison?

A. Yeah. Well, I – see, I didn't know

he was going to escape, but my other brother John had visited him the day before he escaped. And James told him he was going to escape and for him to come down and pick him up and which John did. And John brought him straight to Chicago, and we rented a room at the Fairview.

I didn't know all this. They rented the room, then they called me up. John called me up, and I came in and we all stayed at the Fairview that night. That's on South Michigan Avenue in Chicago. So that was how they escaped. Then after that, John went back to St. Louis. We used to give James $100 because he didn't have no money. He escaped.

So John went back to St. Louis and James – and I went back to work the next day. Then James got a paper and he found an ad in there at Klinglens (spelled phonetically) Restaurant in Winnetka, and Winnetka is only a few miles from where I'm at. And he went to work there, and we used to meet every week or so at a bar there in

North Brook, Illinois.

Q. Well, where were you working at the time?

A. I was working at the Sportsman's Country Club in North Brook, Illinois. That's about five or seven miles from where he was working at.

Q. And you would then see him from time to time?

A. Yeah, every week or every other week.

Q. Did John have any more contact with him?

A. No. Once John left us, you know, the Fairview Hotel in Chicago, he never had no contact with James until he got back to Memphis. You know, when he was brought back from England.

Q. You mean he had no contact with him from the time he escaped to the time he was captured?

A. Yeah, the day after James escaped, John left and went back to St. Louis and I went out to work. And John didn't ever have no contact with him after that.

Q. So were you the only family member who had contact with James?

A. Yeah, the only one. He called me every once in a while.

Q. During his fugitivity?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. How long did he stay at this job in Winnetka?

A. Let's see, he stayed there close to three months.

Q. What did he do after this job?

A. Well, he saved up a few dollars that he could save up, and he bought an old car. I think it was a '57 Dodge because he was talking when he escaped, when John was there too, when he got out, he had to get out of the country, see, and he had to leave because he had all this time to back up. And not only the 20 years then for escape and everything. So he told John – John heard that too, and he told me, he said I'm going to try – I'm going to save up some money and go to Canada and try to figure out a way to get out of the country. And so that's what

he did. He saved up. He worked there about three months and he bought an old junker, old Dodge. Then I met him the night before he took off and then he took off and went to Canada.

Q. Do you recall the date that you met him before he left for Canada?

A. No, I don't recall. It was about a day before that he took off for Canada.

Q. Which month was it?

A. That was in July.

Q. Was it –

A. July of '67.

Q. Was it toward the end of July?

A. It was either the middle or late part of July, and the only reason I know, my birthday is the 16th, so it was a little bit after that.

Q. Sometime after that?

A. Yeah.

Q. And he left and went to Canada?

A. And went to Canada.

Q. Did you have any contact with him when he was in Canada?

A. No.

Q. When was the next time you saw or heard from your brother James?

A. Well, the next time I heard from him and I can't, you know, quote the days because I don't keep diaries or nothing, but I guess it was about six, seven weeks afterwards.

And I think it was in September, probably late September. He had this pay phone, where I didn't have no phone in my room.

I worked at the country club where you get room and board, and we had this pay phone in the hallway. And he had the number. That's how you get a hold of me.

Well, he called one day or one evening and told me to come to Chicago because he knew my day off. He arrived where so I would have the day off. He said don't bring your car in because I'm going to give you my car, and so then – so then I took a train.

They had the Northwestern that runs in down in the loop and he met me down there. And we spent the night together, had breakfast together, and he was talking to

me. And he was all happy and, hell, he was – he had plenty of money on him. So he said I'm going to go down to Birmingham and buy a late model car. He said you can have this. He said I'm working now, and he mentioned Raul.

I can't exactly remember how the Raul came in. I worked for a guy named Raul or something like that, but then he said – he had a big box of stuff. He said take this to Union Station – that's a railroad station downtown Chicago – and mail this down to me at Birmingham and mail it to Eric S. Galt. He said from now on I'll be known as Eric S. Galt. And so that's what I did, and he gave me the car. Then I took him to the station, and later on I mailed that stuff down to him as Eric S. Galt.

Q. So he came back from Canada. He had a job so he told you.

A. He told me he had a job working down there.

Q. He was working for somebody he met in Canada?

A. Yeah, and he mentioned his name – Raul.

Q. Somebody called Raul?

A. Yeah.

Q. Did he tell you what the job was?

A. No. I knew it was something illegal. I figured it was dope or car theft or something. You know, I didn't know what it was, and I didn't actually care that much, but I knew it was something illegal because he was trying – he said he was working this, you know, this guy he called Raul to get enough money so he could get out of the country, you know, get out of Canada and the United States totally.

Q. So he was doing – taking on this job, whatever it was, so that he could get out of the country?

A. Yeah, get out of the country.

Q. That was the reason he went to Canada in the first place?

A. Yeah, and I didn't actually – I kind of wish I had of now because, you know, I'd know more to testify to, but I didn't know

more about it. But right then I wasn't even inquisitive because I knew he was doing something illegal and then met some guy over there and this guy is paying him to run dope or whatever he's doing. And I don't even think half the time he knew what he was doing because they just had him drop a car off in Mexico and drop one off in New Orleans.

Q. So after he saw you, you talked with him in Illinois and he went to Birmingham, did you have any contact with him over the course of the next year?

A. Well, up until the time King got killed, from the time we left Chicago when I seen him last, he called me three times.

Q. And what did he say on those?

A. It wasn't nothing. It wasn't nothing but just I'm working or asking how the family is and this and that. And every call would be under three minutes because I hear him put the change in and the operator would never come on. It would be less than three minutes each call. So probably – I probably talked to him about six, seven minutes since the

last time I met him when he left Chicago until King got killed.

Q. That's the only contact you had with him?

A. The only contact I ever had with him after that.

Q. Have you ever known your brother James over all the years you knew him when he was free or when he was inside even –

A. Yeah.

Q. – did you ever know him to engage in violence?

A. Never. He never had. He never had – the most violent thing he ever did was rob a store, you know, the Kroger store.

That's the most violent ever, but there never was no violence used in that, you know. And in fact, before that he was always, you know, like a burglar. You know, like breaking in and stealing money, but then when he got with that – I mentioned his name before – Owens. Owens did robbery, see, so then he went in on the robbery.

Q. In the course of this time when he

was on the run after he returned to the United States and those three phone calls that you had with him, did he ever mention Dr. Martin Luther King?

A. No. The King name never came up when we was in the hotel when we met together and stayed all night or in no phone calls. The King name was never mentioned, and the last thing James was thinking about was, you know, Jackson or King or Kennedy or any of them people because he was trying to stay out of prison.

Q. So there was no mention of them?

A. No.

Q. Was there any mention of any activity that he was being asked to do related to Dr. King?

A. No, never nothing.

Q. Now, eventually he went to England, was extradited and was imprisoned in the United States?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you have more contact with him after that?

A. Oh, yeah, I was coming down here to Memphis back in '68 when they brought him back about every week, and I'd drive down and we'd visit. And what they had – like Mark Lane said, he was treated worse than prisoners of war, you know, the guys they tried in Nuremberg. He had a TV set on 24 hours a day and the lights. They xeroxed all of his mail, and they had him on TV all the time, you know, hooked up. And so when we would visit, he would have to write me notes and flash them because otherwise they would know everything that he knew.

Q. Did he give you the impression that he was determined to go to trial?

A. He was determined. He was determined. That's the only thing he wanted was a trial because he said he'd have to go to trial. He said only way I can, you know, convince the people that I'm not guilty and try to show the people where I'm at was take a trial. That was the first trouble he had with his first attorney Haynes because William Bradford Huie told Haynes that James

Earl Ray can't take the stand because if he takes the witness stand, I don't have no book. So that's when he replaced him.

Q. Well, there was a contractual relationship between a book writer and his first lawyer?

A. Yeah, Arthur Haynes went over to England, the first attorney James had, and he brought a contract over for him to sign that he would represent him if he signed that contract where he'd get all the royalties off the books, you know. And so then William Bradford Huie was the one that paid him the money.

In fact, before he fired Haynes on November 1st of 1968, I flew down to Harpersville, Alabama and talked to Huie. Huie paid my way down there because he wanted another contact besides the attorney so he was showing me these contracts, and he's talking about changing them around where James would get the money because his idea was he'd pay your money. He'll even brag that everybody has got their – you know,

paid.

And so I told him – he told me, he said the only thing is now you go back and tell James he's not going to take the witness stand because if he does, I don't have no book. So I went back and told James you ought to fire Haynes because Huie is running the case.

Q. Well, the writer told you that James shouldn't take the witness stand when he went to trial?

A. Yeah, that was later on in a – later on in a phone conversation with the – later on in a conversation with Mark Lane –

Q. Well, we'll come to that conversation.

A. Yeah.

Q. And in the event, James did not have a trial?

A. No, he never had no trial.

Q. How did that come about when he was so determined to have one?

A. Well, what he done when Arthur Haynes told him he couldn't take the witness stand

and James said that's the only way I can, you know – because he couldn't give these lawyers like Haynes – every time you give him some information, a phone number or something, he'd give it to Huie. And he said how can I get a trial when they know everything I'm going to testify to.

And so when he got rid of Arthur Haynes, then he got Percy Foreman, and Percy Foreman came in and said this is going to be the easiest case I ever had in my life.

There's no evidence at all against him, and he did that up until about a month before the guilty plea.

Then he started crying saying they're going to execute him, they're going to do this, do this. And so James asked him to resign from the case because he was determined to go to trial anyway, and Foreman wouldn't resign. And Judge Battle said if he fired Foreman, he had to go to trial with a public defender.

Q. So the result was that he didn't go to trial?

A. No, he didn't go.

Q. He pled guilty?

A. Yeah, Percy Foreman pled him guilty.

Q. I'm going show to you a letter, Jerry, that was written to James Earl Ray by Percy Foreman.

(Document passed to witness.)

Q. Take your time, please, and read it.

A. Yeah, I know all about this.

Q. What is the date of –

A. This is May the 9th –

Q. What is the date of that letter?

A. March the 9th, 1969.

Q. March what?

A. 9th.

Q. March 9th, 1969?

A. Yeah.

Q. And when was the guilty plea hearing?

A. Right around that time.

Q. If I may inform them, it was March 10th. As a matter of fact, it was March 10th –

A. Yeah.

Q. – the following day.

A. Yeah.

Q. And what is the purpose of that letter from Foreman, his attorney, to James? What does he tell him there?

A. Well, James told me – you know, I went down there when Foreman tried to get him to plead guilty. And he said he's still, you know, was fighting against it. He said what I'll do, I'll have Percy Foreman to give you $500 before I'll plead guilty. Then you can go down and get another attorney to reopen the case in which I used the money, the $500, I flew down to New Orleans. This is even in a book because the guy I went down to see about an attorney, he didn't trust me. He didn't know what I was coming down there for so he notified the police and the FBI. And we met in the park and the police was all out in the park.

Q. Let's focus on this. This is a letter from his counsel on the eve of trial, and this letter offers you – offers him $500.

A. Yeah, if –

Q. Under what conditions was he offered $500 by –

A. Yeah, if he don't do no – if he pleads guilty and don't embarrass him in the court. That was the agreement.

Q. And that $500 –

A. And he went along with the guilty plea. He put in a guilty plea.

Q. We understand that $500 was to be taken to hire a new lawyer to try to set it aside?

A. Yes.

Q. Was there in fact an application to set aside that guilty plea shortly thereafter?

A. As soon as James got to Nashville, he wrote a letter to Judge Preston Battle and asked him to take the letter for motion for a new trial and that Percy Foreman has been relieved. And when Battle died a few days – I don't know, 20 days or whatever it was after the guilty plea, he had three letters from James asking for a trial.

MR. PEPPER: Your Honor,

plaintiffs move admission of this letter.

(Whereupon, the above-mentioned document was marked as Exhibit 19.)

Q. (BY MR. PEPPER) So he pled guilty and was sentenced to 99 years. Did there come a time when you had further contact with William Bradford Huie?

A. Yes, back in – I think October I believe it was of 1977 when James Earl Ray escaped from Brushy Mountain Prison. His attorney then was Jack Kershaw, and I knew – I had known Mark Lane, an attorney.

And Playboy came out with a dirty story about my brother so I recommended to James that he get Mark Lane to represent him. So Mark Lane took over the case. Just before he escaped, the trial was supposed to start. That was in October.

Q. Let me try to move you through to the point at hand. Did you have a conversation with William Bradford Huie around that time, October of 1977?

A. Yes, sir. The day after the escape trial, I called William Bradford Huie.

Q. And James had been in prison then for approximately eight years?

A. Yeah.

Q. And in the course of that conversation, did Bradford Huie make an offer to you –

A. He made –

Q. – to take to James?

A. Yeah, he made an offer, and we got it on tape. He made an offer that we taped for $220,000 if I get him in to see James.

Q. Well, he wasn't paying $220,000 for a visit.

A. No, no.

Q. What was the offer?

A. $220,000 if he would tell him about killing King and he had to give him, you know, a story about that he killed King and that – he said that's the only way a book will sell if you write a book that he killed King.

Q. What would James do with $220,000 if he was in prison?

A. Well, he said that – he explained

that – he started off with that Blanton was the governor, and he said we get James out through Blanton and you and James both can live good in another country.

Q. So he was going to arrange a pardon?

A. Yes, through Governor Ray Blanton.

Q. Did you record that telephone conversation?

A. Yeah, it was all taped. Me and Mark Lane taped it.

Q. And was there a transcription of that recording?

A. Yes.

Q. Let me show you this transcription.

(Document passed to witness.)

Q. Would you tell the Court and the jury what is the heading of that transcription, the date, time and place?

A. It's October 29, 1977, a.m. – 9:45 a.m. Jerry William – Jerry Ray or William Ray, Bradford Huie, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, rural Scottish Inn.

Q. Would you just look through that transcription and see if you recognize it as

the transcription that was made of the tape recording of that conversation?

A. Yeah, that's it.

MR. PEPPER: Plaintiffs move the transcription into evidence.

(Whereupon, the above-mentioned document was marked as Exhibit 20.)

Q. (BY MR. PEPPER) What happened to the tape of that conversation?

A. Mark Lane made the tape and he turned the copy over to the House assassination Committee that was investigating the King assassination of Kennedy at the time, and he kept the other one.

Q. So the House Select Committee on Assassinations had a copy of that tape recording?

A. Yes, had a copy of it.

Q. That same committee decided that there was no Raul?

A. Yeah.

Q. Is that right?

A. That's right.

Q. And that in fact James got his money

that he said Raul gave him from robbing a particular bank in Alton, Illinois?

A. That's right.

Q. Did James rob that bank in Alton, Illinois to the best of your knowledge?

A. No. I don't know who robbed that bank. It's still unsolved. I know they had claimed that me and James robbed the Bank of Alton.

Q. They not only claimed that, there was a front page, column one article in the New York Times on the 17th of November 1978. I'd like to show you that article.

(Document passed to witness.)

A. Yeah.

Q. Now, that article claims, does it not, that the Times investigation, the FBI investigation and the congressional investigation all –

A. Yeah.

Q. – concluded that you and your brother robbed that bank?

A. Yeah, robbed that bank.

Q. Did you take any steps yourself as a

result of those charges?

A. Well, what happened was I was in St. Louis and James was testifying in Washington in front of the assassination committee, and they said we're going to prove you and your brothers robbed the Bank of Alton and used the money to finance the King killing. So a friendly reporter there named James Alber (spelled phonetically) – Mark Lane had called him the same day they accused us when he got a recess from the assassination committee and asked him to take me over there and waive the statute of limitations.

And so Alton, Illinois is only about 20 miles from St. Louis, Missouri. So we drove over there and we went in the police station. First, we went in the bank and they had a different president then. And so then we went down to the police station and I turned myself in and waived the statute of limitation so they could prosecute me. And they said are you here to confess to the crime. I said I can't confess to a crime

that I didn't commit, but I said Congress accused me of committing a crime so I'm here to stand trial. He said you never was a suspect.

Q. The police officials in Alton, Illinois said you never were a suspect?

A. Never was a suspect.

Q. Did they ever explain to you how this type of article got written?

A. No, no. They was mystified that, you know, they even accused me of doing anything, and so I don't know if it was FBI making stuff up or where it's coming at. But it became – and like I say, I knew I couldn't have been a suspect because I worked from '65 to '68 in the North Brook – Sportsman's Country Club in North Brook. Never was late, worked six nights a week, never was late or never missed a day.

Q. Did they tell you that they had been interviewed by the New York Times?

A. No, they didn't say anything.

Q. There was no reporter from the New York Times that interviewed them?

A. Not that I know of.

Q. Did they tell you they had been interviewed by a House Select Committee investigator?

A. No.

Q. Did they tell you they had been interviewed by the FBI?

A. No. As far as that, no, nobody had ever talked to them about it as far as I know because they didn't say anything about it to me.

Q. Yet somehow this appears column one, New York Times, byline Windell Walls, Junior.

A. Yeah.

Q. 17th of November.

A. See, I don't know if this has anything to do with it, but in 1981, F. Lee Bailey had a TV show called Lie Detector on and they threw me out there. We did two lie detector tests, and I got tapes of the test put away. And one, if I was involved in the King assassination and the one was was I involved in any bank robberies. And we did two shows and both showed I was innocent. I

wasn't involved in no bank robberies or no Assassinations.

Q. Mr. Ray, let me show you an FBI air-tel dated on July 19th which supplements one of 7-26-68, and it has to do with an FBI review of all fingerprints related to bank robberies at the time in question.

(Document passed to witness.)

Q. What is the conclusion of the bureau's analysis of all of the fingerprints of suspects at that time with respect to James Earl Ray? This is a comparison of your brother's fingerprints.

A. According to this, they took fingerprints and it wasn't his. They couldn't pick up his fingerprints.

Q. What's the last two or three words?

A. The last – no identification effected.

Q. And that was in '68?

A. That was in – let's see, where is it? 8-1-68 I think. Yeah, or 8-2-68.

Q. About a year after –

A. The bank was robbed.

Q. – the bank was robbed and some nine years before the allegations again surfaced?

A. Yeah.

Q. Did you testify before the Select Committee on Assassinations?

A. Yes, I testified.

Q. Did they raise this issue with you?

A. Yeah, they raised the bank robbery. I couldn't believe it when they raised the bank robbery. I told them, I said, what, are you pulling a joke here? I said I've been over to the bank and the police station and turned myself in. Oh, we're not playing no joke he said and so – but then they basically got off that bank. And at first, he started on the banks and the races and all this other stuff. Every time they had a different reason the reason he killed King.

Q. Do you know what the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded with respect to whether or not your brother was a racist when racism was a motive in this crime?

A. Yeah, even they admit that wasn't

true, that he wasn't a racist. They went through his background, our whole family backgrounds, and they couldn't find nothing in our backgrounds.

Q. Moving on, Mr. Ray, did it ever occur to you in the course of your brother's imprisonment, either to him or to you, to contact the family of the victim in this case?

A. I thought about the King family a lot over the years, and in a way I wanted to, but James – I talked to James about it. He said don't bother them people. He said they've had, you know – they've lost that. He said they're liable to look at you and think you're the brother of the murderer. He didn't know how they felt, see, and it wasn't until he was dying then a lady reporter from the New York Times called me up. And I don't remember her name.

And she asked me if I would talk to the King family if I had a chance, and I said sure I'd talk to them. And I told her the same thing. I said if me and James ever

talked to them, he goes we'd be out of order, you know, trying to talk to them. And then this reporter told Dexter or Coretta King what I said and that's how we got talking together.

Q. And that's how the communication started?

A. Yeah, that's how the communication started.

Q. Were you surprised when they took a position in support of a trial for your brother?

A. I was because I knew it was going to hurt them bad because the government media, they're going to really come down on them like they come down on the Ray family. So it surprised me because I knew for all these years they've been getting good press, and all at once, the press is going to turn against them.

MR. PEPPER: Thank you, Mr. Ray.

THE WITNESS: Thank you.

MR. PEPPER: No further questions.

THE COURT: Let's see if Mr. Garrison has any questions for you.

BY MR. GARRISON:

Q. Mr. Ray, you and I have talked previously a few times.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you understand we're here trying to get the truth.

A. Yeah, that's what we're after, the truth.

Q. Let the chips fall where they may. You understand that, don't you?

A. Yes.

Q. Let me ask you something. Going back to the time that your brother escaped from prison, how long had he been serving then? How long had he been in the prison there?

A. He had already been in seven years and he had a 20-year sentence.

Q. And had he made some effort to escape before this time?

A. Yes, he had tried to escape before. Two or three times – I forget exactly.

Q. Did he ever state to you that he had any contact or any influence with a warden of that prison?

A. No, he never did. In fact, like I said, I only visited him a couple times in seven years at the prison. And John, I don't know, my other brother, he visited him maybe four or five times. But when I went down there them two times, it was just a friendly visit.

Q. And when he escaped, you said I believe that you met him the next day?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And where was that that you met him?

A. Well, John brought him up. John picked him up when he escaped and he brought him to the Fairview Hotel. That's on South Michigan Avenue in Chicago.

Q. And his plan at that time was to get a job and then try to get into Canada?

A. Yeah, he – the next day – we all three stayed together that night, and the next day John drove back to St. Louis and I went back to North Brook. But before we did,

we each give him $100.

Q. Okay. Mr. Ray, let me ask you something. You – after the assassination, you talked to your brother I know several times or at some time to confer with him?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you ever ask him who he thought did the assassination?

A. Not completely. He knew some way that they know who done it and that it's being covered by the FBI, but he didn't know who done it or why it was done. And everybody got their own speculations and that's why even until the day he died, he fought to get these files released that's locked up and won't be released for another 30 years. And Clinton said they could be released, but they still won't release them.

Q. Why are those files sealed for 30 years? Have you been told?

A. Like James said before he died, they didn't seal them files to protect me.

Q. Who sealed the files?

A. The assassination committee, they had

them sealed and then I guess with Congress.

Q. Let me ask you, as you know, I've spent two days taking your brother's testimony in prison. Did you ever see him with this person called Raul?

A. No, no, I never – I only heard him mention his name one time. That's when he came back from Canada.

Q. Did you – did he tell you that Raul was financing him and helping him?

A. Yeah, he said he was working for Raul.

Q. What kind of work was he doing for Raul?

A. I don't know. I knew it was something illegal. I assumed gun or drugs or something because he's telling me about taking them cars to different cities, you know, and dropping them off so I figured it was narcotics.

Q. Do you know – did you have any discussion with your brother before he entered a guilty plea? Did you have any conference with him about that?

A. Yeah, I came down to visit him. See, everything we said was taped so you have to watch what you say and they got the lights and everything because I didn't want to see him plead guilty. I knew what struggle he was on, but he told me too the last time I seen him he still hadn't made up his mind.

He was still fighting to go to court, and he told me that Foreman told him if he didn't plead guilty, they was going to put my dad in prison which my dad had jumped parole back in the twenties and was going to charge me as being an accessory to the murder.

Q. Let me ask you, did you know he was going to escape before he did?

A. No, I didn't know that. John did. I didn't.

Q. You had no knowledge?

A. No. I was working up in North Brook. I was working there like I say six nights a week.

Q. Did he ever mention to you as to how he came up with these aliases that he had, where he got those names from? He had

several aliases.

A. No, I never did – I knew a couple of them – a Harvey Lomar he used. I grew up with a guy named Harvey Lomar, a friend of mine in Quincy, Illinois, but the other one like the Eric S. Galt and the Ramone Sneyd, I didn't know how he got them.

Q. Mr. Pepper asked you about the congressional committee. You testified in that, didn't you?

A. Yes.

Q. All right. And the conclusion was that your brother was the one that did the assassination, wasn't it?

A. I think their conclusion – if I remember right, they claimed that he heard of a $50,000 bounty while he was in the Missouri prison and he went out and killed King but didn't pick up the bounty and took off. That was actually kind of a sad joke. Here you're going to go out and commit a crime and all this money spent traveling all over the world and don't pick up the bounty. Yeah, there's supposed to have been two guys, Sutherland

and Kauffmann, in St. Louis supposed to have been racists that put up the $50,000 bounty, but they was both dead.

Q. Mr. Ray, had you ever heard anything about a bounty from someone in Missouri on Dr. King's life?

A. No. The only thing I heard is what the assassination committee – when they came out, that's the first I heard of it.

Q. Did your brother ever mention to you that he was ever in a place called Jim's Grill at any time?

A. No, I don't – see, the only thing I can remember, he was telling me about where he was at at the time that King got killed. He was at a service station trying to get a tire fixed, but he never did hardly mention Jim's Grill to me. I'm not saying he wasn't in there because I don't know.

Q. Let me ask you this. Did he tell you that the day this happened that he had gone up to this rooming house and had registered as a guest, paid some money? Did he ever tell you that or did he tell you what he was

doing there?

A. Oh, yeah, he told me that I think it was at the DeSoto Motel he had bought this gun – was in Birmingham I think it was. And then he – then Raul said it was the wrong one and he had to take it back and get another one, and he told him to meet him at that motel in DeSoto. Then he picked the gun up or Raul picked the gun up that night and later on told him to rent a room on this place on Main Street.

Q. Did he tell you that he had gone into the rooming house and had taken any of his clothing or personal items?

A. No, I didn't ask him what he brought in there. I never did – the only thing I knew, he went in there and they had – later on that night had Raul and another guy in there. And he said that Raul used his car a lot, that Mustang, so Raul told him he wanted to use the car later that time and he wanted to talk to this guy, you know, by himself anyway. So James told him, he said I'll go get the tire fixed. He had a flat

tire coming in, and that's when he went up to get the tire fixed.

Q. He spent some time in Atlanta, did he not, before the assassination?

A. Yeah. He lived in Atlanta. I can't remember the name of the place he lived at, but some apartment places in Atlanta.

Q. Okay. Mr. Ray, let me ask you this. You're aware of the fact that after the assassination, a map was found that your brother owned that had a home, business and another location where Dr. King stayed that was supposed to be part of his property. You're aware of that, aren't you?

A. Yeah, I've read that.

Q. Have you ever seen the map?

A. No. The only thing I know is what I read. I read something that something was circled – a church or –

Q. A church and his office I believe was circled.

A. Yeah.

Q. Did you ever see the Mustang that was supposed to be driven by your brother – the

white Mustang?

A. No. I've never seen it in my life to this day because I never did see James after he left Chicago. Then when they took the Mustang, I think they sold it to somebody here in Memphis – a car lot.

Q. After the assassination on April 4th, 1968, when did you hear from your brother again? Did you talk to him any more after that, the 4th?

A. No. After – I can't remember for sure. I think it was about two months before the assassination. Then the next time I talked to him is when they brought him back from England to Memphis.

Q. So you had not talked to him from the assassination up until he was brought back?

A. Until he was brought back. And within a week after he was brought back, I drove down and visited him.

Q. Did you know where he was during that time?

A. Oh, no, no. See, the FBI would keep me in their office all day long after they

had discovered they was looking for James Earl Ray. And the FBI, they would take me downtown. I was working at night and in there all day because the FBI told me if he ever gets in touch with you, will you let us know, and I said you'll know before I know.

Q. Well, did he ever mention anything about the fact that this Raul had indicated to him that they wanted to assassinate Dr. King? Was anything ever said about that?

A. No, no, no. Huh-uh, no. He never had got involved in anything like that – no murder or nothing like that. The only thing he was trying to do was just make enough money to get out of the country, and he said that guy's paying him good.

Q. Mr. Raul was paying him?

A. Yeah. He only mentioned Raul's name once by name, and right after that he said he's paying him good. And I believe he was talking about the same person.

Q. Let me ask you this. Mr. Ray was never seen anywhere with this Raul that you know of, was he?

A. Well, I don't think Mr. Pepper brought or Attorney Pepper brought this up, but James sent me down twice – once right after the guilty plea. That's what that $500 was for, to go down to New Orleans, because he'd meet Raul in the Bunny Lounge. That's on Canal Street.

Q. What was the name of that?

A. The Bunny Lounge – Bunny lounge. And it's on Canal Street. And James told me exactly where it was at, and I went in there and had two barmaids – and I mentioned Raul, you know, like on a friendly term.

Otherwise, you get suspicion and they want to know what's going on. And the barmaid hadn't heard of Raul. Then I asked another one about Randy – Randy Rosenson because one time after Raul used a car, when James got it back, it had a card stuck down in the side. And on it, it had Randy Rosenson's name on there and a phone number. And so then James sent me down again in about '72 and trying to run this guy down. So then that's when a barmaid said, well, that's

probably Randolph Rosenson.

So I go back, and James then – she says something about he lives in Miami. And so then I go back in and James had me fly down to Miami and go to check up on Randolph Rosenson. They subpoenaed him in front of the assassination committeeu, but I don't know what the outcome was. But anyway, his card was found in James' Mustang after Raul used it one time.

Q. When your brother testified before the assassination committee, were you there present?

A. No, I was in St. Louis. I watched it on live TV.

Q. Were you surprised that he entered a guilty plea?

A. Yeah, I was. I was. I was. Most people – I've talked to a lot of people that in a way don't believe he's guilty, but why would he plead guilty to something like this if he didn't do it and –

Q. Did you ever ask him that very question?

A. Yeah, well, he kicked himself after he got out of that place they had him in, see, and he said that's the worse mistake I ever made in my life because it's hard to overturn. But like Mark Lane and them talked about that.

That was worse where he was at than the Nazis they put on trial in World War II after Nuremberg because they had the lights on, the heat on, they had a policeman in there with him 24 hours a day and he'd breathe everything he done. And he couldn't get no visitors. If he did, he had to write notes to them unless you wanted the state to know what he was talking about. Then on top of that, Foreman said they were going to put me in prison and put my dad in prison if he didn't plead guilty.

Q. Did you ever know that your brother owned a rifle of any type? Did you ever know of any type rifle he owned?

A. No, huh-uh. He wasn't a good shot anyway, see, if he shot anything. I think they classify you when he went in the Army

and he was a poor shot.

Q. Mr. Ray, was your brother in Los Angeles some of this time after he escaped from the Missouri prison?

A. Yeah, he spent time – I didn't know about it at the time. I found out later he was out in L.A. a lot.

Q. But you learned he was in Los Angeles some of the time?

A. Yeah.

MR. GARRISON: That's all, Your Honor.

THE COURT: All right.

MR. PEPPER: Nothing further, Your Honor.

THE COURT: All right. Mr. Ray, you may stand down. You can remain in the courtroom or you're free to leave.

THE WITNESS: Okay. Thank you.

(Witness excused.)

THE COURT: At this point we're going to take break.

(Jury out.)

(Break taken at 11:40 a.m.)

THE COURT: Let's bring the jury out, please, sir.

(Jury in at 12:07 p.m.)

THE COURT: Call your next witness.

MS. AKINS: Good morning, Your Honor. We have two statements – FBI reports, 302's. Both are taken or one taken April 25th, 1968.

Mr. Ray Alvis Hendrix, Room 14, Fox Hotel, 106 Vine Street, Memphis Tennessee, advised that he is employed by the Corps of Engineers, U.S. Government on the Dredge Oakerson. Mr. Hendrix stated he worked about six months in nice weather and is off the other six months of the year.

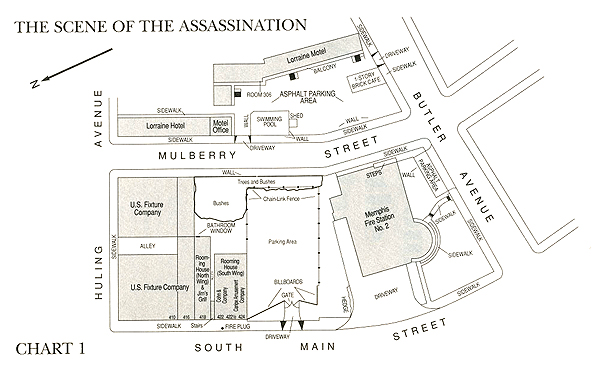

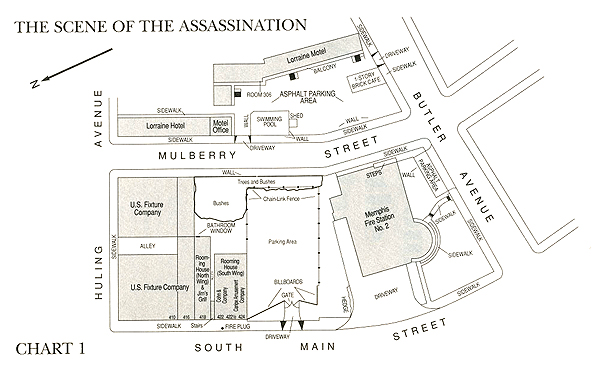

Mr. Hendrix stated that on the evening of April the 4th, 1968, he and Bill Reed, who resides in Room 4 of this hotel, ate their dinner at Jim's Grill located at 418 South Main Street, Memphis, Tennessee.

He stated they left the grill at approximately 5:30 p.m. and slowly walked to the Fox Hotel. He said they walked on the

east side of South Main Street.

Mr. Hendrix commented that when they left Jim's Grill he forgot his jacket and had to return for the jacket. He said he learned later that while he was getting his jacket, Bill Reed looked at a white Mustang that was parked almost in front of Jim's Grill. He said he did not notice this Mustang or any other cars parked in front of Jim's grill.

He stated, however, that when he and Bill Reed approached the intersection of Vance and South Main Street, Bill Reed pulled him back to the curb because the car was turning the corner. He said this car was a white Mustang and that after the car turned the corner Bill Reed commented to him that this was the Mustang that was parked in front of Jim's Grill which he looked at while he, Hendrix, was retrieving his jacket.

Mr. Hendrix stated he did not see who was in the car but believes there was only one person. He said he could not describe him and would not be able to identify the driver of this car.

Mr. Hendrix stated that as they were returning to their rooms or possibly or just entering their rooms, they heard sirens in the immediate area and going south on South Main Street. He said he later learned that the sirens were from police cars that were going to the scene of the murder of Martin Luther King. He said as near as he can recall, he heard the siren about 6:00 p.m. or just a few minutes after 6:00 p.m. on April the 4th, 1968.

Mr. Hendrix stated that the Mustang had turned the corner and proceeded east on Vance Street, did not turn the corner very fast or made the tires squeal. He said he did not watch which way the Mustang turned or how far it traveled on Vance Street.

Mr. Hendrix also stated he could not furnish any information as to the cars parked or traveling in the immediate area of Jim's Grill at the time that he and Bill Reed left. He also stated he could not furnish any information concerning individuals in the immediate area of Jim's Grill at the time he

left to return to his room.

THE COURT: What's Mr. Hendrix's first name?

MS. AKINS: Ray Alvis Hendrix.

THE COURT: Thank you.

MS. AKINS: Your Honor, the second statement, also FBI report number 302, was taken April the 15th, 1968, by Mr. William Zinny Reed. These are pages 66 and 67.

Room 6, Clark Hotel, 106 Vance Street, Memphis, advised he is employed as a salesman for a photography firm and is currently working in the Memphis area. Mr. Reed stated that on April the 4th, 1968, he and Ray Hendrix stopped at Jim's Grill, 418 South Main Street for something to eat. He said he was in Jim's Grill for some time and feels that he arrived there at approximately 4:30 p.m. and believes that he left between 5:15 p.m. and 5:30 p.m.

He said when he left, he picked up his hat and he and Ray Hendrix paid their check and left Jim's Grill. He said that

they left the entrance of Jim's Grill and proceeded north on South Main Street for 10 feet when Ray Hendrix remembered he left his jacket in Jim's Grill. Mr. Reed stated he waited in front of Jim's Grill while Hendrix went back for his jacket.

He commented that while waiting, he looked and saw a white Mustang was parked near the entrance of Jim's Grill. Mr. Reed stated he does not have a car and is in the market for a car and was considering buying a Mustang and therefore he looked this car over. He said he believed the car was an off white color, that it was not dirty but was not exactly clean either.

He said he believes this car had not been recently washed. He said he does not recall the color of the interior but believes that it was a dark color. He said he does not recall seeing anything inside the car other than five cartons lying on the back seat. He described these cartons as being the size of a tin package cigarette carton. He said these cartons were red and

white in color, but does not remember any lettering on the cartons nor does he remember whether the white or the red was dominant.

He said when he saw these cartons he felt that the owner of this car was probably a traveling salesman – that the owner of this car was probably a traveling salesman.

Mr. Reed stated he does not know whether or not any stickers were in the window of this car and he did not look at the license. He said he does not recall if the Mustang had whitewall tires and if it had wheel covers.

Mr. Reed stated that after Hendrix obtained his jacket from Jim's Grill, they proceeded north on South Main and walked on the east side of South Main Street. He said when they arrived at the intersection of Vance and South Main, he was about ready to walk off the curb when for some unknown reason he looked around to see if there were any cars coming. He said as he looked back, he saw a white Mustang about ready to turn the corner and go east on Vance from South

Main Street.

He said he does not know if this is the same car he saw parked in front of Jim's Grill but added it seemed to be the same car. He said he did not see who was in the car but believes it was a white male with a white shirt, but does not recall if this individual had a tie or hat on. He said he had the impression this person was not young but was not old. He said he would have no way of estimating the age of this person.

Mr. Reed said the Mustang proceeded east down Vance Street. He has no idea where the car went after it turned the corner.

Mr. Reed stated that he went to his room and that he had been in his room for quite some time, possibly as much as 15 minutes when he heard numerous sirens in the immediate area going down toward Jim's Grill. He said he learned later that Martin Luther King had been shot and that the sirens he heard were from officers going to that immediate area.

Mr. Reed advised he could not

furnish any additional information concerning any cars parked on the street or any people in that immediate area.