TUC aka Time of Useful Consciousness is an aeronautical term. The time between the onset of oxygen deficiency and the loss of consciousness, the brief moments in which a pilot may save the plane.

Into Eternity © Magic Hour Films |

MICHAEL MADSEN / FILM DIRECTOR

We call it Onkalo. Onkalo means “hiding place”. In my time it is still unfinished though work began in the 20th century when I was just a child. Work would be completed in the 22nd century long after my death.

Onkalo must last one hundred thousand years. Nothing built by man has lasted even a tenth of that time span. But we consider ourselves a very potent civilization.

If we succeed, Onkalo will most likely be the longest lasting remains of our civilization. If you, sometime far into the future, find this, what will it tell you about us?

The voice of Danish artist and film maker Michael Madsen from the opening of his film: Into Eternity. These words were first heard in the US in early 2011 when Into Eternity was released in North American.

Onkalo is the first in the world – after Yucca Mountain failed technologically as well as politically in the U.S. – and the only project to create a permanent storage for waste from nuclear power plants.

Madsen takes us to the remote island of Olkiluoto (“ol-key-lu-oh-toe”) on the shores of the Baltic Sea in Finland. Underground we meet the blasters who set off the explosions that create the vast system of tunnels. And above the various technicians, scientists, and regulators involved in this project.[1]

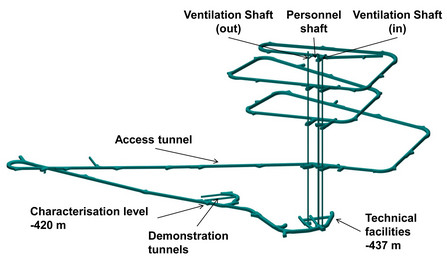

For the next hundred years the multiple tunnels and chambers of Onkalo, which stretch to a depth of fifteen hundred feet [500 metres], will house all of Finland’s nuclear waste, until it is filled and sealed with cement in 2120.

No person working on the facility today will live to see it completed. To protect life from the highly radioactive nuclear power plant fuel, the waste must lay untouched for 100,000 years. Onkalo is being designed to far outlast any structure or institution ever created by mankind.

What are 100,000 years in relation to known history? Since it is so difficult to predict the future, we usually look back:

- The Great Pyramid of Giza was completed around 4,500 years ago,

- the transition from nomadic hunter gathering to farming and permanent settlement occurred between 7 and 10 thousand years ago,

- the last ice age was 20,000 years ago,

- our Homo sapiens ancestors only reached Europe 40 thousand years ago, where Neanderthals did not become extinct until 30 thousand years ago

- and the great original Homo sapiens migration out of Africa took place between 125 and 60 thousand years ago.

My thoughts, in viewing the film, Into Eternity, post-Fukushima, were that as insane as it appears to embark on a project of building storage to last 100,000 years, it is even more insane to continue the practice of keeping the so-called “spent” nuclear fuel[2] right next to the most dangerous places on earth, in unprotected fuel pools next to nuclear power plants. And most insane, I think and we may soon all realize to produce electricity with nuclear fuel in the first place.

At the moment there is at least 250,000 tonnes of radioactive waste on Earth. Onkalo, after all these efforts, will be able to hold a tiny fraction of 6,500 tonnes.[3]

For some time the nuclear industry has claimed nuclear fuel will be re-processed. However, in this chain of mounting absurdities, reprocessing creates plutonium, that will have to be kept safe not for 100,000 but for one million years. Unless it is used in a nuclear weapons with the potential to destroy the planet instantly.

Back to the film. Here is KRAFTWERK:

TIMO SEPPÄLÄ / SENIOR MANAGER, COMMUNICATIONS

ONKALO

So we are storing the waste above ground in water pools.Radioactivity

Is in the air for you and me

Radioactivity

Discovered by Madame Curie

Radioactivity

Tune in to the melody

Radioactivity

Is in the air for you and me[4]

TIMO SEPPÄLÄ

The reason why it's kept in water pools is that water creates a seal for radiation.

PETER WIKBERG / RESEARCH DIRECTOR

NUCLEAR FUEL AND WASTE MANAGEMENT, SWEDEN

Keeping the waste in tanks is probably possible for the next 10 years, 20 years, 100 years, 1,000 years.

TIMO SEPPÄLÄ

You just can't guarantee stable conditions above ground, for instance, for one hundred years, let alone thousands of years. . . .

We can't keep this waste forever in the water pools.

There has been two world wars during the last 100 years. The world above ground is unstable. We have to find a permanent solution. Or a more safe solution in the long run.

MICHAEL MADSEN / FILM DIRECTOR

My civilization depends on energy as no civilization before us. Energy is the main currency for us. Is it the same for you? Does your way of life also depend on unlimited energy?

PETER WIKBERG

What we must do, is to take care of the waste from the nuclear power plants.

TIMO ÄIKÄS / EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, ENGINEERING

ONKALO

I think that more and more societies in countries who are using nuclear power are realizing that they also have to do something.

PETER WIKBERG

We obtained the energy. We have used the energy. Of course it's our mission to also take care of the waste.

TIMO ÄIKÄS

There is no way of doing nothing.

TIMO SEPPÄLÄ

Final disposal of spent nuclear fuel hasn't been implemented anywhere so far. We are kind of forerunners in this field. And we are dealing with very, very long time frames. Meaning that this repository should last at least 100,000 years.

MICHAEL MADSEN

A hundred thousand years is beyond our understanding and imagination. Our history is so short in comparison. How is it with you? How far into the future will your way of life have consequences?

When I saw the film at the opening in San Francisco, two months after the explosions at Fukushima and one month after the word Fukushima had already disappeared from the headlines of the newspapers, I thought of a review that I had read on the internet. Alexander wrote in Soft morning, city!:

Onkalo is probably the most ambitious human endeavour ever put into practise, and in its quiet, reflective style, the film Into Eternity presents the project in its full madness. It makes us consider the big questions in a way that we, in the 21st century, don’t usually do outside of theological and philosophical circles. Questions of war, economic collapse, mass migration, ecological catastrophe, societal structure, all seem to pale away when we are faced with a time period that, in reverse, stretches back tens of thousands of years beyond our recorded history, to when Homo sapiens, or modern humans, were not the only species of human on this Earth. This is an idea that is almost inconceivable to us now. For all the questions thrown up by Onkalo, and of all the possible and predicted events occurring in its lifespan, only one can approach definite status as a likely event over others. It is inevitable that one day, in the next 100,000 years, Onkalo will be discovered by someone. Any argument against this seems the utmost in arrogance and wishful thinking. [5]

I wondered how the construction firm that designed and bid on the project of Onkalo may have presented their proposal to the government of Finland. And there it was:

DEMO NARRATOR No.1

Olkiluoto in Eurajoki has been chosen as the site for the disposal facility for spent nuclear fuel. Onkalo.[6]

TIMO ÄIKÄS

The repository acts like a cocoon if you like, or a Russian Doll where you have barriers which complement each other. So that if one barrier might fail, other barriers still are able to mitigate all the consequences.

DEMO NARRATOR No.2

The final diposal facility will be constructed in stages and decommissioned in the two thousand one hundreds.

DEMO NARRATOR No.3

When the entire tunnel is ready a thick concrete closure is cast at the tunnel mouth.

MICHAEL MADSEN

We will fill the chambers of Onkalo with the nuclear wastes from Finland, from just one little country in the north. After one century we will seal Onkalo for all eternity. Just like the tombs of the Pharaohs in the pyramids were sealed thousands of years ago never to be opened again.

PETER WIKBERG

There will be forests. There will be houses. Hopefully there will still be people living. Not perhaps exactly the same persons that were there from the beginning. But perhaps their children and grandchildren will still live and use the land.

We always bring up the question of the ice age as some kind of a very dramatic change in the situation. And of course it will have an impact. But if we look at our assumptions, the scenarios, it will happen within 60,000 years from now.

The film, Into Eternity reflects much of the discussion on how to create markers on the surface to warn future generations of the danger below. Nothing could be found that would be understood 100,000 years from now – if any physical marker were to even survive the ice age that will be pushing glaciers over Onkalo 60,000 years from now.

The discussion in the film reminded me of the report that the Sandia National Laboratories published in 1991. The US Department of Energy had commissioned Sandia to create a plan to keep burial grounds of nuclear waste safe from future generations.

The report was called: Expert Judgement on Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.[7]

In essence the report said that no language, no plaques with symbols, no ominous looking structures on top of the burial were guaranteed to be understood, even only 10,000 years into the future.[8]

The most realistic plan, some of the members of the Sandia National Labs commission felt, would be to endow a nuclear priesthood committed to guarding the site and transmitting the memory orally from generation to generation.

Much of the discussion in Finland, documented in the film Into Eternity, comes up with similar ideas. The Onkalo project staff, like Sandia Labs, recognized that nothing might work unless it became part of a living transmission.

And even if future generations were to somehow understand the warning, would they heed it? In our time line the Pyramids were opened and rune stones moved in spite of warnings.

MICHAEL MADSEN

We have no archives with information on nuclear waste yet. But if we built archives every future society and every future generation must maintain the information and update the language for you to understand.

Can we count on continuation for thousands of generations into the future? What if people starve and suffer? What if there are wars or floods or fires? The archives have the same requirements as our interim storages. Requirements we cannot guarantee. After all, this is why we are building Onkalo.

And so, in the end, some of those interviewed argue that it may be better not to mark the repository at all. That remembering to forget is the best protection. But how will that work for all the future Onkalos that yet must be built for two hundred and fifty thousand tonnes of nuclear waste? How many such places can you hide?

MICHAEL MADSEN

Onkalo is our very first permanent repository for nuclear waste. But when Onkalo is sealed a century from now, it will hold only a fraction of the waste we have. We must build many more Onkalos far from earthquakes and volcanos to keep the waste away from the surface of the earth. We must build many more secret chambers that we hope to hide from you.

QUESTION

Do you think it is reasonable to talk about a nuclear renaissance?

JUHANI VIRA / SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, RESEARCH

ONKALO

Many people seem to think so. And many politicians believe that nuclear energy is needed to curb the carbon dioxide emissions from electricity production.

BERIT LUNDQVIST / SCIENCE EDITOR

NUCLEAR FUEL AND WASTE MANAGEMENT, SWEDEN

[If] we're going to take the people in China and in India to the same level as the western countries in the next 20 years, you have to start 3 new nuclear reactors a day.

The film, Into Eternity, is a documentary about the building of the world's first underground storage site for waste from nuclear power plants. The tiny country of Finland decided to take responsibility for the nuclear waste it created – and continues to create – and became the pioneer, both technologically and philosophically, of trying to come to terms with nuclear power.

How far ahead can we burden the earth and future generations by turning on the lights?

Peter Bradshaw, wrote in the British Guardian,

“One of the most extraordinary factual films to be shown this year. Madsen's film does not merely ask tough questions about the implications of nuclear energy . . . but [also] about how we, as a race, conceive our own future. . . . This is nothing less than post-human architecture we are talking about. Why isn't every government, every philosopher, every theologian, [everybody,] everywhere in the world discussing Onkalo and its implications?”[9]

MICHAEL MADSEN

Once upon a time, man learned to master fire. Something no other living creature had done before him. Man conquered the entire world. One day he found a new fire. A fire so powerful that it could never be extinguished. Man reveled in the thought that he now possessed the powers of the universe. Then in horror, he realized that his new fire could not only create but also destroy. Not only could it burn on land but inside all living creatures; inside his children, the animals, all crops. Man looked around for help, but found none. And so he built a burial chamber deep in the bowels of the earth, a hiding place for the the fire to burn, into eternity.

Into Eternity was written and directed by Michael Madsen. You heard his voice as narrator, along with engineers and regulators for the Onkalo project. The film is beautifully photographed by Heikki Färm with an haunting and intriguing sound design by Nicolai Link and Oivind Weingaarde. You may have recognized the piece Radioactivity by the German electronic group Kraftwerk.[10] Their name, curiously, translates into power plant. Coal I assume, not nuclear.

Director Michael Madsen is based in Copenhagen and the 75 minute film is a co-production between Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

The film opened for European audiences in 2010 and began showing in the U.S. in New York shortly before the explosions at Fukushima. Ever since that catastrophe the parallel between the way the film shows the handling of spent nuclear fuel and the diligent building of underground storage clashes with what occurred in Fukushima.

The film shows the careful removal of so-called spent fuel from the fuel pools to the dangerous and complex procedure of placing the rods into canisters for later transfer into Onkalo. That now stands in frightening and stark contrast to the images of collapsed fuel pools and molten fuel rods that can no longer be handled.[11] Does Fukushima itself have to become a site for storage of what cannot be removed by man or robot that needs to last maybe as long as one hundred thousand years? On the beach, open to the next tsunami, near an earthquake zone?

The movie's web site is www.intoeternitythemovie.com. That web site also has an excellent section on Nuclear Facts. For example:

High-level nuclear waste is the inevitable end result of nuclear energy production. The waste will remain radioactive and/or radiotoxic for at least 100,000 years. It is estimated that the total amount of high-level nuclear waste in the world today is between 250,000 and 300,000 tons. The amount of waste increases daily.

Spent nuclear fuel is normally kept in water pools in interim storages. Almost all interim storages are on the ground surface, where they are vulnerable to natural or man-made disasters, and extensive surveillance, security management, and maintenance is required. The water in the pools cools the fuel rods, as the heat emanating from them may otherwise result in radioactive fire, and at the same time, water creates a shield for radioactivity. It takes 40 - 60 years to cool the fuel rods down to a temperature below 100 degrees Celsius. Only below this temperature may the spent fuel be handled or processed further.

Those were some Nuclear Facts from the website of the intoeternitythemovie.com.

You can hear this program again on TUC Radio’s web site tucradio.org. That’s tucradio.o-r-g Look under newest programs.[12]

TUC Radio has moved to northern California. This program was produced off the grid, with power from the sun; the only safe nuclear reactor.

You can get information on how to order an audio CD of Into Eternity that includes the talks by Joanna Macy and Natalia Manzurova by calling 1-707-463-2654 and I will repeat that number in a moment.

TUC Radio is free to all radio stations and depends on the support of listeners like you. Your donation or CD order keeps this program on the air. Call anytime at 707-463-2654 for information on how to order. You can get your CD by mail or credit card by phone or online on TUC Radio's secure website, tucradio.org.

My name is Maria Gilardin. Thank you for listening. Give us a call.

Annotated transcription created with permission of Maria Gilardin.

-

Onkalo is the world’s first permanent nuclear waste repository.

From the Nuclear

Facts section of intoeternitythemovie.com:

Onkalo is a Finnish word for hiding place. It is situated at Olkiluoto in Finland – approx. 300 km northwest of Helsinki and it's the world's first attempt at a permanent repository. It is a huge system of underground tunnels hewn out of solid bedrock. Work on the concept behind the facility commenced in 1970s and the repository is expected to be backfilled and decommissioned in the 2100s – more than a century from now. No person working on the facility today will live to see it completed. The Finnish and Swedish Nuclear Authorities are collaborating on the project, and Sweden is planning a similar facility, but has not begun the actual construction of it.

The ONKALO project in Finland is described on a section of the website presented by the builder, Posiva Oy. The company is headquartered on the island of Olkiluoto in the municipality of Eurajoki. This local PDF copy of a report by Posiva Oy – ONKALO - Underground Rock Characterisation Facility at Olkiluoto, Eurajoki, Finland – comes from http://www.posiva.fi/files/375/Onkalo_ENG_290306_kevyt.pdf and was accessed on 11 February 2012.

The Posiva website contains a section on The Principles for Final Disposal that describes the KBS-3 concept – the multiple protective barriers principle for radioactive materials – developed by SKB (Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co) the company responsible for nuclear waste management in Sweden.

-

Spent fuel means high level nuclear waste. This radioactive

matter is kept in water pools where it must be cooled for

40 to 60 years to bring it down to below 100 degrees Celsius

so it can be handled for further processing. From the

Nuclear

Facts section of

intoeternitythemovie.com:

High-level nuclear waste is the inevitable end result of nuclear energy production. The waste will remain radioactive and/or radiotoxic for at least 100 000 years. It is estimated that the total amount of high-level nuclear waste in the world today is between 250 000 and 300 000 tons. The amount of waste increases daily.

See Also:

Spent nuclear fuel is normally kept in water pools in interim storages. Almost all interim storages are on the ground surface, where they are vulnerable to natural or man-made disasters, and extensive surveillance, security management, and maintenance is required. The water in the pools cools the fuel rods, as the heat emanating from them may otherwise result in radioactive fire, and at the same time, water creates a shield for radioactivity. It takes 40-60 years to cool the fuel rods down to a temperature below 100 degrees Celsius. Only below this temperature may the spent fuel be handled or processed further. Most interim storages are situated near nuclear power plants, as the transportation of waste is complicated, and subject to extensive security issues.-

From Wikipedia:

- High-level radioactive waste management

-

Spent fuel pool

spent fuel pools (SFP) are storage pools for spent fuel from nuclear reactors -

Spent nuclear fuel

Spent nuclear fuel, occasionally called used nuclear fuel, is nuclear fuel that has been irradiated in a nuclear reactor (usually at a nuclear power plant). It is no longer useful in sustaining a nuclear reaction in an ordinary thermal reactor. -

Spent Fuel

Storage in Pools and Dry Casks

Key Points and Questions & Answers,

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) -

Nuclear Waste -

Disposal Challenges and Lessons Learned from Yucca Mountain,

Government Accountability Office, GAO-11-731T, Jun 1, 2011

-

It is not clear what the total tonnage of radioactive waste

is projected to be that will fill Onkalo before it is sealed in

2120.

The date for sealing Onkalo is based on information given in Posiva's Frequently Asked Questions:-

When will final disposal begin?

According to the schedule determined by the Government, final disposal is intended to begin in 2020. Planning of final disposal has progressed according to this schedule. -

How long will the final disposal of the spent fuel take?

The final disposal of spent fuel from the existing nuclear power plant units and the Olkiluoto 3 unit currently under construction will take about 100 years.

As to the total amount of tonnes that will fill Onkalo, the above FAQ says,-

How much nuclear fuel is spent each year?

In the annual maintenance of the Loviisa 1-2 and Olkiluoto 1-2 plant units, the reactors are filled with approximately 70 tonnes of new fuel. An equal amount is transferred to spent fuel storages to await final disposal. -

What will be the total amount of spent fuel?

According to existing plans, the Loviisa 1-2, Olkiluoto 1-2 and Olkiluoto 3 plant units will produce electricity for 50-60 years. Production results in about 5,500 tonnes of spent fuel. In addition, the construction of the intended Olkiluoto 4 and Loviisa 3 plant units would mean that an approximate total of 12,000 tonnes of uranium would be consumed in 60 years of electricity production. -

What is the waste disposal capacity of Olkiluoto?

Based on existing know-how and the bedrock surveys already conducted, the feasibility and safety of the final disposal has been assessed for the spent fuel of the existing plant units, the Olkiluoto 3 unit under construction, and two new nuclear power plant units. The total amount of spent fuel is 12,000 tonnes of uranium.

Maria Gilardin used another transcript of the film with the figure of 6,500 tonnes for this broadcast. In her weekly radio program, If You Love This Planet, Dr. Helen Caldicott interviewed Michael Madsen on 15 July 2011. At one point Dr. Caldicott asked, “How much nuclear waste do the Finns actually have in terms of tonnage?” to which Madsen responded:To return to the amount of waste in Finland, I can't remember the figure but the idea is that in 120 years from now 15,000 metric tons is the capacity of the Onkalo facility. And that will by that time hold all of the waste in Finland.

And there are other sources with other figures as well:

But the problem is now that another private operator has been granted a license to build another power plant in Finland and the waste production from this [new] power plant is not calculated in relation to the Onkalo facility.

So they will have to build their own facility also. Because the private company, Posiva, behind the Onkalo facility does not want to [share their technical knowledge] – I mean it's their facility.

And what is so weird, in my opinion, about this is that the money this is financing the Posiva company building this [Onkalo] facility – and I believe the cost is something like 3 billion euros – that money is coming from a tax taken from the Finnish citizens ever since their nuclear energy production started. So this is paid [for] by every Finnish citizen.

But now the know-how rests within private companies. And other companies cannot use this. It's simply a competition parameter. That is a peculiarity, in my mind.

-

Finland

keeps faith with nuclear power,

by John Pagni, 22 June 2011, Utility Week.

Finland's Nuclear Energy Act requires operators to dispose of nuclear waste permanently and responsibly, which led to Posiva, a subsidiary of TVO and Fortum, being founded. . . . The assemblies are cooled in water pools in separate intermediary facilities from the nuclear power plant (a problem at Fukushima) for 40 years before they go to Onkalo forever. Onkalo's capacity is sufficient to take 9,000 tonnes of nuclear waste from TVO and Fortum. -

Dispute

over disposal of nuclear waste brewing between power companies,

Pyhäjoki waste would not all fit in Olkiluoto,

Helsingin Sanomat, INTERNATIONAL EDITION, 7 October 2011

Posiva is currently excavating a final storage area for waste from TVO and Fortum in the bedrock in Olkiluoto, where encapsulated nuclear waste is to be placed as of the 2020s. At present, the waste is still being kept in interim storage in Olkiluoto and Loviisa. The network of tunnels is to have space for nuclear waste from seven nuclear reactors – a total of 2,800 capsules.

From “Dispute over disposal” above, does anyone know how much a capsule weighs? (Please contact me if so.) And below, is it that in Finland there are currently 5,500 metric tons and in 100 or more years there will be 12,000 metric tons of radioactive matter generated from nuclear power plants? And is “capsule” above the same as “fuel bundle” below?-

Finland's

Nuclear Waste Solution, Scandinavians are leading the world in

the disposal of spent nuclear fuel, by Sandra Upson, December 2009,

IEEE Spectrum

There’s more at stake here than the interment of 5,500 metric tons of spent Finnish fuel. More than 50 years after the first commercial nuclear power plants went operational in the United Kingdom and the United States, the world’s 270.000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel remain in limbo. . . .

As much as 12,000 metric tons of uranium – alongside the other isotopes and zirconium rods – may eventually find their way into Onkalo. The facility will pack away at least 27,000 fuel bundles, and more may follow from Finland’s projected nuclear power production through 2080.

-

When will final disposal begin?

-

From Wikipedia:

Radio-Activity

(German title: Radio-Aktivit’t) is the fifth studio album by German

electronic band Kraftwerk, released in October 1975. Unlike Kraftwerk's later

albums, which featured language-specific lyrics, only the titles differ between

the English and German editions. A concept album, Radio-Activity is

bilingual, featuring lyrics in both languages.

“Radioactivity”

(original German language title: "Radioaktivit’t") is a song written by

Ralf Hütter, Florian Schneider and Emil Schult, and recorded by electronic

band Kraftwerk as the title track of their 1975 album Radio-Activity.

-

“Onkalo,

Into Eternity, and Faulkner's homemade spaceship,”

Alexander,

Soft morning, city!,

20 April 2011

-

Watch the

Onkalo

Animation from the

Posiva Oy

company website. Other information in the ONKALO section includes:

ONKALO

One element of the site investigations conducted at Olkiluoto is the excavation of the underground rock characterisation facility (ONKALO) that will be extended to the final disposal depth (approximately -400m).ONKALO aids in collecting the further data needed for the application for the construction licence that will be submitted in 2012. The bedrock is studied with methods from geology, hydrology and geochemistry.

In addition to facilitating bedrock research, ONKALO also provides an opportunity to develop excavation techniques and final disposal techniques in realistic conditions. Later, the ONKALO facilities can be put into use when building and using the repository.

Posiva started to construct ONKALO in 2004. Research has been conducted there since the beginning of its construction.

ONKALO consists of one access tunnel and three shafts: a personnel shaft and two ventilation shafts. The slope of the tunnel is 1:10. It is 5.5 m wide and 6.3 m high.

-

“Expert

Judgement on Inadvertent Human Intrusion into

the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant,”

by Kathleen M. Trauth, Stephen C. Hora, Robert V. Guzowski,

SANDIA REPORT, SAND92-1382- UC-721, Unlimited Release,

Printed November 1993, Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories,

Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550

for the United States Department of Energy

under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000.

-

The U.S. Department of Energy's Waste

Isolation Pilot Plant site has a section on

Passive

Institutional Controls that includes a number of reports attempting to

address the question of how to communicate with the distant future.

Of special interest to the makers of Into Eternity is a Los Alamos National

Laboratory (PDF) report conducted in 1990 titled,

“Ten

Thousand Years of Solitude? On Inadvertent Intrusion into the Waste

Isolation Pilot Project Repository.” Quoting from the

movie's Source

Links section: “The only other substantial study in this

direction, apart from work by Mikael

Jensen, SKB, seems to be Roland Posners (editor) Warnungen an die

ferne Zukunft (Warning for the distant future): Raben-Verlag 1990”

Also in this collection of reports is a copy of the First Web-page titled, WIPP Exhibit: Message to 12,000 A.D. used to explain warning messages and early concepts with the opening text stating:

This place is not a place of honor.

No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here.

Nothing valued is here.

This place is a message and part of a system of messages.

Pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us.

We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

And there are original drawings of proposed markers shown in Into Eternity:

-

Into Eternity - review

This jaw-dropping documentary tackles a subject almost beyond comprehension

by Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, 11 November 2010

Bradshaw observes that to our descendants in the future, “Onkalo might seem an unimaginably mysterious shrine to the gods. And is that, in fact, precisely what we are building here? My blood ran cold as one engineer involved in this project said that the project had to be "independent of human nature".”

This editor wishes that Bradshaw had included the word everybody in the last sentence quoted above. The implications of what our species is engaged in at Onkalo is not only for every government, every philosopher, every theologian in the world to discuss and come to terms with. It is for all our human species to grapple with.

-

From Wikipedia:

Radio-Activity (German title: Radio-Aktivit’t) is the fifth studio album by German electronic band Kraftwerk, released in October 1975. Unlike Kraftwerk's later albums, which featured language-specific lyrics, only the titles differ between the English and German editions. A concept album, Radio-Activity is bilingual, featuring lyrics in both languages.

Kraftwerk (German pronunciation: [ˈkʀaftvɛɐk], meaning power plant or power station) is an influential electronic music band from Düsseldorf, Germany. -

See Fukushima

Daiichi Nuclear Plant Photographs. This is a subset of data mirrored from

cryptome.org of photographs and documents presented in the

Nuclear Power Plants and Weapons Series.

- In http://tucradio.org/new.html, this program is the second half hour of the broadcast titled, “NUCLEAR ETERNITY at Chernobyl, Fukushima and Onkalo.”