by Dr. Helen Caldicott

15 July 2011

Listen to the interview at: http://ifyoulovethisplanet.org/?p=4732

Complete Transcript of 15 July 2011 interview with Michael Madsen on

ifyoulovethisplanet.org,

A Weekly Radio Program with Dr. Helen Caldicott.

Michael Madsen on the staggering problem

of storing the world's nuclear waste

|

Michael Madsen, the Danish director of the new documentary film “Into Eternity”, joins Dr. Caldicott for a riveting conversation with worldwide implications. “Into Eternity” focuses on the vast amounts of radioactive waste created every day by nuclear power plants the world over, and the constant challenge to find an adequate way to store it, with a special emphasis on the Onkalo nuclear waste repository being built in Finland (to be completed in 120 years). Read two 2011 articles about the film: ‘Into Eternity’: Effort to store nuclear waste and Nukes are forever which includes the trailer for the film. Check out Conversation with Michael Madsen: Director of Into Eternity which includes stills from the documentary. Also read the 2006 BBC article Finland buries its nuclear past. To learn more about Madsen’s film and inquire about future DVD sales, visit intoeternitythemovie.com.

Welcome to If You Love This Planet. I'm Doctor Helen Caldicott and in this program we talk about the greatest medical and environmental threats to all life such as nuclear weapons and nuclear power, global warming, ozone depletion, toxic pollution, deforestation, and many other social and political issues that relate to global well being. So if you love this planet, keep listening.

I am interested in the areas of documentary filmmaking where additional reality is created. By this I mean, that I do not think reality constitutes a fixed entity which accordingly can be documented or revealed in this or that respect. Instead, I suspect reality to be dependent on and susceptible to the nature of it's interpretation. I am in other words interested in the potentials and requirements of how reality can be – and is – interpreted.Can you just, Michael, enlarge on that last point – “out of time,” “emblematic of our time,” – can you tell us what you mean by that?

The ONKALO project of creating the world's first final nuclear waste facility capable of lasting at least 100,000 years, transgresses both in construction and on a philosophical level all previous human endeavors. It represents something new. And as such I suspect it to be emblematic of our time – and in a strange way out of time, a unique vantage point for any documentary.

To listen to previous shows, or to make a donation, go to our website, IfYouLoveThisPlanet.org.

Annotated transcription created with permission of Dr. Helen Caldicott and Jasmin Williams.

-

Into Eternity - review

This jaw-dropping documentary tackles a subject almost beyond comprehension

by Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, 11 November 2010

-

To Damascus (2005); See

IMDb

Full cast and crew listing. From a “News” page

of the Transilvania International Film Festival,

quoting Michael

Madsen:

“TO DAMASCUS (2005) was inspired, in terms of narrative and emotions, by Strindberg’ first so-called dream-play – essentially about being alienated, not able to trust your own feelings. I had two co-directors, and to equate Strindberg’s feelings, we drove in a car from Copenhagen to Damascus trying to film things with emotional connections with the play. We knew we had to go southwest, and our only guide was the sun reflected in the right rear mirror. For sure we made a lot of detours, including three weeks in Romania. In the end it was essentially made in the editing room – with a ratio of 100:1. A nightmare!”

-

Interim facility refers to the process of Interim storage.

From the Nuclear

Facts section of intoeternitythemovie.com:

High-level nuclear waste is the inevitable end result of nuclear energy production. The waste will remain radioactive and/or radiotoxic for at least 100 000 years. It is estimated that the total amount of high-level nuclear waste in the world today is between 250 000 and 300 000 tons. The amount of waste increases daily.

Spent fuel means high level nuclear waste. See Also:

Spent nuclear fuel is normally kept in water pools in interim storages. Almost all interim storages are on the ground surface, where they are vulnerable to natural or man-made disasters, and extensive surveillance, security management, and maintenance is required. The water in the pools cools the fuel rods, as the heat emanating from them may otherwise result in radioactive fire, and at the same time, water creates a shield for radioactivity. It takes 40-60 years to cool the fuel rods down to a temperature below 100 degrees Celsius. Only below this temperature may the spent fuel be handled or processed further. Most interim storages are situated near nuclear power plants, as the transportation of waste is complicated, and subject to extensive security issues.-

From Wikipedia:

- High-level radioactive waste management

-

Spent fuel pool

spent fuel pools (SFP) are storage pools for spent fuel from nuclear reactors -

Spent nuclear fuel

Spent nuclear fuel, occasionally called used nuclear fuel, is nuclear fuel that has been irradiated in a nuclear reactor (usually at a nuclear power plant). It is no longer useful in sustaining a nuclear reaction in an ordinary thermal reactor. -

Spent Fuel

Storage in Pools and Dry Casks

Key Points and Questions & Answers,

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) -

Nuclear Waste -

Disposal Challenges and Lessons Learned from Yucca Mountain,

Government Accountability Office, GAO-11-731T, Jun 1, 2011

-

Onkalo is the world’s first permanent nuclear waste repository.

From the Nuclear

Facts section of intoeternitythemovie.com:

Onkalo is a Finnish word for hiding place. It is situated at Olkiluoto in Finland – approx. 300 km northwest of Helsinki and it's the world's first attempt at a permanent repository. It is a huge system of underground tunnels hewn out of solid bedrock. Work on the concept behind the facility commenced in 1970s and the repository is expected to be backfilled and decommissioned in the 2100s – more than a century from now. No person working on the facility today will live to see it completed. The Finnish and Swedish Nuclear Authorities are collaborating on the project, and Sweden is planning a similar facility, but has not begun the actual construction of it.

The ONKALO project in Finland is described on a section of the website presented by the builder, Posiva Oy. The company is headquartered on the island of Olkiluoto in the municipality of Eurajoki. This local PDF copy of a report by Posiva Oy – ONKALO - Underground Rock Characterisation Facility at Olkiluoto, Eurajoki, Finland – comes from http://www.posiva.fi/files/375/Onkalo_ENG_290306_kevyt.pdf and was accessed on 11 February 2012.

See Also: A corporate promo animation of building Onkalo by Posvia.

-

Regarding this statement “in the Swedish legislation concerning

high-level nuclear waste, the talk is about creatures, living

creatures, and not just humans,” I asked Michael Madsen

if there was legislation containing this wording. He responded:

I just talked on the phone with Mikael Jensen [see Cast listing]. The above is not mentioned directly anywhere in the Swedish law. However in the different areas of what concerns the environment, it can implicitly be interpreted to be implicitly present. Mikael has himself, as this was part of his job at the Swedish Nuclear Safety Agency, advocated for this to be included as he has used it as an implicit example of what can be the de facto case in the future. So it has been discussed – also as a means to try to make these time spans comprehensible for today's policy makers.

-

I asked Michael Madsen for more information about the law in

Finland he refers to here, including the name of the legislation

and the year it was passed or enacted. His responded with:

I am forwarding mail I received from Esko Ruokola [see Cast listing] who is STUK's law-writer. Apart from this, I have never understood where the 100,000 years comes from, but this is what Posiva and STUK both mentioned to me. France, as in the US, says 1 million years.

The e-mail Michael Madsen forwarded me was written by Esko Ruokola in 2008:The statements in legislation and regulations are given below:

References to the above Finish Regulations are as follows:

The Nuclear Energy Act[A] states the following:The Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK) shall be entitled, in order to carry out the supervision required under this Act, and by the provisions issued hereunder and by Finland’s international treaties in the field of nuclear energy, to:

The Nuclear Energy Decree[B] continues the story with the following statement:

. . .

6) issue prohibitions on measures concerning real estate when this is necessary in order to secure safety, when that real estate includes premises referred to in paragraph 5b of section 3. (738/2000)The Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK) shall report the disposal site of nuclear waste and the prohibition on measures, referred to in paragraph 6 of section 63 subsection 1 of the Nuclear Energy Act, so that they can be entered in the real estate register, land register or list of titles.

Finally, the Government Decree to be issued soon (will replace the Government Decision 398/91[C]) includes the following statements:A record shall be kept of the disposed wastes which includes waste package specific information on waste type, radioactive substances, location in the waste emplacement rooms and other necessary data. The Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority shall arrange for the depositing the information about the disposal facility and disposed waste in a permanent manner.

An adequate protection zone shall be reserved around the disposal facility as a provision for the prohibitions on measures referred to in the Nuclear Energy Act (990/87), Section 63, first paragraph, point 6.- Nuclear

Energy Act 11.12.1987/990

The first segment of this quote is from the beginning of Chapter 10 Supervision and coercive measures, Section 63 Supervisory rights. - Nuclear

Energy Decree 12.2.1988/161

quoting Chapter 12 Nuclear waste management, Section 85 - Decision

of the Council of State on the general regulations for the safety of a

disposal facility for reactor waste 14.2.1991/398

The section with wording close to that of the 2 paragraphs quoted above is in Section 7 Post-closure surveillance, which apparently is what was replaced by “the Government Decree to be issued soon.”

See Also: from the Source Links section of intoeternitythemovie.com:Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority is the organ of the Finnish state, which oversees the construction of ONKALO, approving it in it’s different stages. It is STUK, which suggest the various legislation to be implemented by the Finnish Parliament concerning nuclear waste and nuclear safety: www.stuk.se.

There is an English version of STUK and an English version of the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority (SRSA). In the SRSA website is a section entitled Final Repository which describes KBS-3:

Swedish Radiation Safety Authority is the Swedish pendent to STUK: www.stralsakerhetsmyndigheten.se

The Finnish Posiva OY is the company behind ONKALO. The technical concept behind ONKALO is called KBS-3, and is originally a Swedish concept, but now in collaboration with SKB [Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co], the Swedish pendent to Posiva. Various reports on conservation and knowledge transfer carried out by SKB, see (PDF in Swedish) fx:

“Identitet och trygghet i tid och rum”

“Kunskapsbevarande för framtiden - Fas 1”Responsibility of industry

Sweden has made use of nuclear power since the 1960s. Today, nuclear energy represents nearly half of the country's production of electricity. In the mid-1970s, the Swedish Government determined that producers of nuclear power were to be responsible for the safe management of spent nuclear fuel, and in 1976, the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (SKB) was established. SKB is collectively owned by the Swedish nuclear power industry. One of SKB's tasks is to develop a method for the safe disposal of spent nuclear fuel for as long a period of time as is necessary to protect people as well as the environment.

SKB’s proposed repository method

SKB's method is called 'KBS-3'. 'KBS' stands for 'nuclear fuel safety' in Swedish, and the number three designates this as the third and most recent version presented by SKB in its research programme.

SKB plans to construct a final repository so that radiation safety is guaranteed by what are known as 'barriers'. The spent nuclear fuel will be placed in canisters with an external shell made of copper and an insert of cast iron. The canisters will be disposed of at a depth of approximately 500 metres in Swedish bedrock. These canisters will be surrounded by a special kind of clay that swells when it comes in contact with groundwater. The entire repository will ultimately be filled with clay.

If you wish to know more about the method developed by SKB, please inquire at its website: www.skb.se. - Nuclear

Energy Act 11.12.1987/990

-

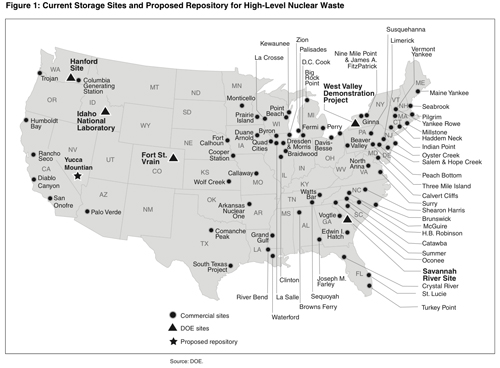

A figure of 75,000 metric tons is cited in the document,

“Nuclear Waste -

Disposal Challenges and Lessons Learned from Yucca Mountain,” published

from the Government Accountability Office,

GAO-11-731T, Jun 1, 2011:

Nuclear energy generates about 20 percent of the nation’s electric power and, as a domestic source of electricity with low emissions, is a critical part of our energy infrastructure. In addition, military use of nuclear material – in nuclear weapons and nuclear-powered warships – plays a vital role in our national defense. However, both of these activities generate nuclear waste – referred to as spent nuclear fuel in the case of fuel removed from a reactor and as high-level waste for material that is a by-product of weapons production and other defense-related activities. This nuclear waste has been accumulating since the mid-1940s and currently totals over 75,000 metric tons at 80 sites in 35 states, enough to fill a football field about 15 feet deep. Furthermore, this waste is expected to increase by about 2,000 metric tons per year, more than doubling, to 153,000 metric tons by 2055.

The majority of this nuclear waste is expected to be spent nuclear fuel from commercial operators. An estimated 13,000 metric tons of this waste, however, is managed by DOE at five of its sites. Existing nuclear waste already exceeds the 70,000 metric ton capacity of the proposed Yucca Mountain repository. -

The U.S. Department of Energy's Waste

Isolation Pilot Plant site has a section on

Passive

Institutional Controls that includes a number of reports trying to

address the question of how to communicate with the distant future.

Of special interest to the makers of Into Eternity is a Los Alamos National

Laboratory (PDF) report conducted in 1990 titled,

“Ten

Thousand Years of Solitude? On Inadvertent Intrusion into the Waste

Isolation Pilot Project Repository.” Quoting from the

movie's Source

Links section: “The only other substantial study in this

direction, apart from work by Mikael

Jensen, SKB, seems to be Roland Posners (editor) Warnungen an die

ferne Zukunft (Warning for the distant future): Raben-Verlag 1990”

Also in this collection of reports is a copy of the First Web-page titled, WIPP Exhibit: Message to 12,000 A.D. used to explain warning messages and early concepts with the opening text stating:This place is not a place of honor.

No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here.

Nothing valued is here.

This place is a message and part of a system of messages.

Pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us.

We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

-

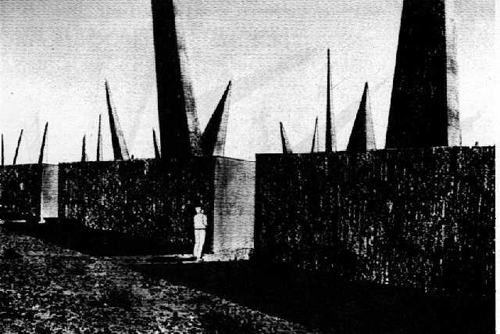

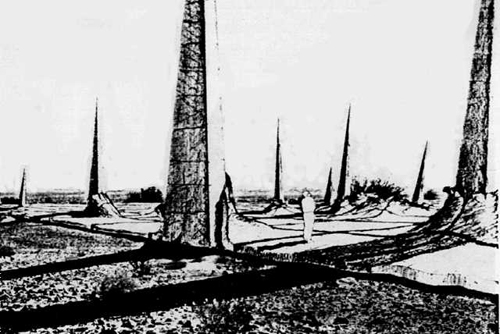

Also included in the

WIPP

Exhibit Message to 12,000 A.D. web page are the original drawings

of proposed markers used in Into Eternity as well:

-

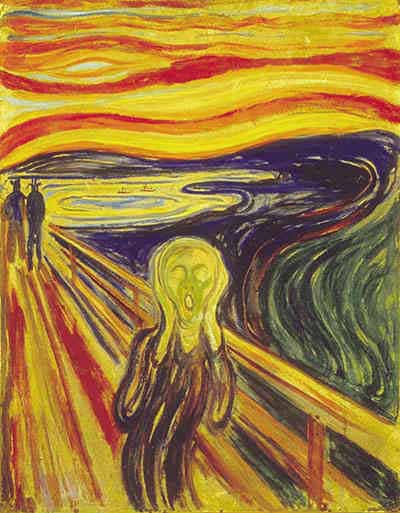

Edvard Munch created several versions of The Scream in various media. Copies of

these are included in

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scream

and are reproduced below:

-

See The Problem:

Nuclear Radiation and its Biological Effects, by

Dr. Rosalie Bertell, Ph.D., G.N.S.H.,

No Immediate Danger, Prognosis for a Radioactive Earth, 1985, pp. 15-63.

See also: What Is Factually Wrong with This Belief: “Harm from Low-Dose Radiation Is Just Hypothetical — Not Proven”, by John W. Gofman, M.D., Ph.D. Committee for Nuclear Responsibility, Fall 1995;

and A Troublesome Trio: Unrepaired ... Unrepairable ... Misrepaired Injuries, from Chapter 18, Disproof of Any Safe Dose or Dose-Rate of Ionizing Radiation, with Respect to Induction of Cancer in Humans of Radiation-Induced Cancer From Low-Dose Exposure, by John W. Gofman, M.D., Ph.D. 1990.

-

See “Asleep at

the Wheel”: The Special Menace of Inherited Afflictions from Ionizing Radiation,

by John W. Gofman, M.D., Ph.D.,

Professor Emeritus of Molecular & Cell Biology, University of California at Berkeley, and

Egan O'Connor, Executive Director, Committee for

Nuclear Responsibility, Fall 1998,

and

A Wake-Up Call for Everyone Who Dislikes Cancer and Inherited Afflictions, by Gofman and O'Connor, CNR, Spring 1997.

-

See the on-going, longterm work being carried out by the

Chernobyl

Research Initiative (CRI) at the University of South Carolina. A

significant member of this group is

Timothy A. Mousseau,

Associate Vice President for Research and Graduate Education, Dean of the Graduate

School (Interim), Professor of Biological Sciences, University of South

Carolina, Columbia. An extensive list of articles is available on the CRI's

Publications Related to Chernobyl page [accessed 12 February 2012] including:

- Møller, A. P., and T.A. Mousseau. 2011. Conservation consequences of Chernobyl and other nuclear accidents. Biological Conservation, 144:2787-2798.

- Møller, A. P., A. Bonisoli-Alquati, G. Rudolfsen, and T.A. Mousseau. 2011. Chernobyl birds have smaller brains. PLoS One 6(2): e16862. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016862 (pdf)

- Mousseau, T.A., and A.P. Møller. 2011. Landscape portrait: A look at the impacts of radioactive contaminants on Chernobyl’s wildlife. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 67(2): 38-46. (DOI: 10.1177/0096340211399747)

- Møller, A.P. and T.A. Mousseau. 2011. Ten ecological and evolutionary questions about Chernobyl. Bulletin of the Chernobyl Zone, In press.

- Møller, A.P. and T.A. Mousseau. 2011. Rigorous methodology for studies of effects of radiation from Chernobyl on animals and humans. Biology Letters of the Royal Society.

- Galvan, I., T.A. Mousseau, and A.P. Møller. 2010. Bird population declines due to radiation exposure at Chernobyl are stronger in species with pheomelanin-based colouration. Oecologia, doi: 10.1007/s00442-010-1860-5

- Bonisoli-Alquati, A., A.P. Møller., G. Rudolfsen, N. Saino, M. Caprioloi, S. Ostermiller, T.A. Mousseau. 2010. The effects of radiation on sperm swimming behavior depend on plasma oxidative status in the barn swallow (Hirundo rustica). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology – Part A – Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 159: 105-112 (DOI: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.018)

- Møller, A. P. and T.A. Mousseau. 2010. Efficiency of bio-indicators for low-level radiation under field conditions Ecological Indicators, doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.06.013 (pdf)

- Møller, A.P., J. Erritzoe, F. Karadas, and T. A. Mousseau. 2010. Historical mutation rates predict susceptibility to radiation in Chernobyl birds. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02074.x (pdf)

- Czirjak, G.A., A.P. Møller, T.A. Mousseau, P. Heeb. 2010. Micro-organisms associated with feathers of barn swallows in radioactively contaminated areas around Chernobyl. Microbial Ecology 60:373-380 (DOI: 10.1007/s00248-010-9716-4). (pdf)

- Møller, A.P., and T.A. Mousseau. 2009. Reduced abundance of insects and spiders linked to radiation at Chernobyl 20 years after the accident. Biology Letters of the Royal Society 5(3): 356-359. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., T.A Mousseau. 2008. Reduced abundance of raptors in radioactively contaminated areas near Chernobyl. Journal of Ornithology, 150(1):239-246. (pdf)

- A.P. Møller, T.A Mousseau. 2007. Species richness and abundance of forest birds in relation to radiation at Chernobyl. Biology Letters of the Royal Society, 3: 483-486. (pdf)

- A.P. Møller, T.A Mousseau. 2007. Determinants of Interspecific Variation in Population Declines of Birds after Exposure to Radiation at Chernobyl. Journal of Applied Ecology, 44: 909-919. (pdf)

- Bonisoli-Alquati, A., A. Voris, T. A. Mousseau, A. P. Møller, N. Saino, and M. Wyatt. 2009. DNA damage in barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) from the Chernobyl region detected by the use of the Comet assay. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, in press. (pdf)

- Bonisoli-Alquati, A., T. A. Mousseau, A. P. Møller, M. Caprioli, and N. Saino. 2009. Increased oxidative stress in barn swallows from the Chernobyl region. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, in press. (pdf)

- E.R. Svendsen, I.E. Kolpakov, Y.I. Stepanova, V.Y. Vdovenko, M.V. Naboka, T.A. Mousseau, L.C. Mohr, D.G. Hoel, W.J.J. Karmaus. 2009. 137Cesium Exposure and Spirometry Measures in Ukrainian Children Affected by the Chernobyl Nuclear Incident. Environmental Health Perspectives, HTML.

- Kravets A.P., T.A. Mousseau, Omel’chenko1 Zh. A., Kozeretska I.A., Vengjen G.S. 2009. Dynamics of hybrid dysgenesis frequency in Drosophila melanogaster following controlled protracted radiation exposure. Cytology and Genetics, in press (in Russian).

- Kravets A.P., Mousseau T.A., Litvinchuk A.V., Ostermiller S., Vengjen G.S. 2009. Wheat seedlings DNA methylation pattern changes at chronic seeds - irradiation. Cytology and Genetics, in press (in Russian).

- Stepanova, E., W. Karmaus, M. Naboka, V. Vdovenko, T. Mousseau, V. Shestopalov, J. Vena, E. Svendsen, D. Underhill, and H. Pastides. 2008. Exposure from the Chernobyl accident had adverse effects on erythrocytes, leukocytes, and, platelets in children in the Narodichesky region, Ukraine. A 6-year follow-up study. Environmental Health, 7:21. (pdf)

- Kozeretska, I.A., A.V. Protsenko, E.S. Afanas’eva, S.R. Rushkovskii, A.I. Chuba, T.A. Mousseau, and A.P. Møller. 2008. Mutation processes in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster and Hirundo rustica from radiation-contaminated regions of Ukraine. Cytology and Genetics 42(4) : 267-271. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., T.A. Mousseau and G. Rudolfsen. 2008. Females affect sperm swimming performance: a field experiment with barn swallows Hirundo rustica. Behavioral Ecology 19(6):1343-1350. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., F. Karadas, & T. A. Mousseau. 2008. Antioxidants in eggs of great tits Parus major from Chernobyl and hatching success. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 178:735-743. (pdf)

- Gashak, S.P., Y.A. Maklyuk, A.M. Maksimenko, V.M. Maksimenko, V.I. Martinenko, I.V. Chizhevsky, M.D. Bondarkov, T.A. Mousseau. 2008. The features of radioactive contamination of small birds in Chernobyl Zone in 2003-2005. Radiobiology and Radioecology 48: 27-47.(Russian). (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., T. A. Mousseau, C. Lynn, S. Ostermiller, and G. Rudolfsen. 2008. Impaired swimming behavior and morphology of sperm from barn swallows Hirundo rustica in Chernobyl. Mutation Research, Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 650:210-216. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., T. A. Mousseau, F. de Lope and N. Saino. 2008. Anecdotes and empirical research in Chernobyl. Biology Letters, 4:65-66. (pdf)

- A.P. Moller, T.A Mousseau. 2007. Birds prefer to breed in sites with low radioactivity in Chernobyl. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 274:1443-1448. (pdf)

- A.P. Moller, T.A. Mousseau, F. de Lope, and N. Saino. 2007. Elevated frequency of abnormalities in barn swallows from Chernobyl. Biology Letters of the Royal Society, 3: 414-417. (pdf)

- O.V. Tsyusko, M.B. Peters, C. Hagen, T.D. Tuberville, T.A. Mousseau, A.P. Moller and T.C. Glenn. 2007. Microsatellite markers isolated from barn swallows (Hirundo rustica). Molecular Ecology Notes, 7: 833-835. (pdf)

- A. P. Møller, T. A. Mousseau. 2006. Biological consequences of Chernobyl: 20 years after the disaster. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 21: 200-207. (pdf)

- A. P. Møller, K. A. Hobson, T. A. Mousseau and A. M. Peklo. 2006. Chernobyl as a population sink for barn swallows: Tracking dispersal using stable isotope profiles. Ecological Applications, 16:1696-1705. (pdf)

- Mousseau, T.A., N. Nelson, & V. Shestopalov. 2005. Don’t underestimate the death rate from Chernobyl. NATURE 437: 1089. (pdf)

- A. P. Møller, T. A. Mousseau, G. Milinevsky, A. Peklo, E. Pysanets and T. Szép. 2005. Condition, reproduction and survival of barn swallows from Chernobyl. Journal of Animal Ecology, 74: 1102-1111. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., Surai, P., and T. A. Mousseau. 2004. Antioxidants, radiation and mutations in barn swallows from Chernobyl. Proceedings of the Royal Society, London, 272: 247-252. (pdf)

- V., M. Naboka, E. Stepanova, E. Skvarska, T. Mousseau, and Y.Serkis. 2004. Risk assessment of morbidity under conditions with different levels of radionuclides and heavy metals. Bulletin of the Chernobyl Zone 24(2): 40-47. (In Ukrainian). (pdf)

- Møller, A. P., and T. A. Mousseau. 2003. Mutation and sexual selection: A test using barn swallows from Chernobyl. Evolution, 57: 2139-2146. (pdf)

- Møller, A. P. & Mousseau, T. A. (2001). Albinism and phenotype of barn swallows Hirundo rustica from Chernobyl. Evolution 55(10): 2097-2104. (pdf)

-

In the United States alone there are 80 such sites in 35 states as described in

the June 1, 2011 document,

“Nuclear Waste -

Disposal Challenges and Lessons Learned from Yucca Mountain,” published

from the Government Accountability Office

(cited above). A map of these sites is included on page 3

(click image to see high resolution version)

Figure 1: Current Storage Sites and Proposed Repository for High-Level Nuclear Waste

-

Links to where can buy a DVD copy of the film for $29.50 or see it on YouTube in 6 parts

are presented at

ratical.org/radiation/IntoEternity/index.html#SeeFilm

-

Olkiluoto 3 is

to be the third reactor at the

Olkiluoto

Power Plant on Olkiluoto Island, on the shore of the Gulf of Bothnia in

the municipality of Eurajoki in western Finland.

-

See

“In

Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble”, by James Kanter, New York

Times, 28 May 2009. See also the following film clips on YouTube:

- Finland is Worried about Olkiluoto 3, Made in Germany | DW-TV EUROPA | 22.03.11 | 22:30 UTC (5:01)

- FINLAND-OLKILUOTO 21.10.2009 ELEKTROWNIA ATOMOWA / NUCLEAR POWER STATION (0:48)

- Olkiluoto 3: EPR(TM) dome installed (2:57)

- AREVA Olkiluoto 3 EPR(TM) Reactor Primary Loop Completion, Uploaded by AREVAinc on Dec 7, 2011, (4:44)

-

The Posiva website describes its

purpose – that includes a

section on Onkalo

– in the following terms:

Posiva Oy

Posiva Oy is an expert organisation responsible for the final disposal of spent nuclear fuel of the owners. Posiva has been established in 1995.

Posiva's Owners

Posiva is owned by Teollisuuden Voima Oyj (60%) and Fortum Power & Heat Oy (40%), both of which share the cost of nuclear waste management.

Posiva's Role in the Nuclear Waste Management Sector

Posiva is responsible for research into the final disposal of spent nuclear fuel of the owners and for the construction, operation and eventual decommissioning and dismantling of the final disposal facility. Additionally, Posiva provides expert nuclear waste management services to its owners and other customers.

Extensive Co-operation

Posiva works together with numerous Finnish and foreign expert organisations from a multitude of fields, and commissions studies related to nuclear waste management from universities and other institutions of higher education as well as from research institutes and consulting businesses.

Posiva's People

In 2011 Posiva employs around 90 people. The company had a turnover of some EUR 61 million in 2010 and is headquartered in Olkiluoto in the municipality of Eurajoki.

SEE ALSO more about Onkalo in footnote 4 above.

-

See In

depth: Chernobyl's Accident Path and extension of the radioactive cloud.

This is a graphic reconstruction of the path of the first 14 days of the

1986 Chernobyl radioactive plume, tracking the release of caesium-137.

It was created by the Institut de Radioprotection et Sûreté

Nucléaire (IRSN), the French

Government's official agency on radiation and nuclear matters. It is a

graphic illustration of the vast extent of radioactive contamination of Europe

(and eventually the rest of the Northern Hemisphere) by the developing

Chernobyl catastrophe.

-

See:

“1945-1998”

by Isao Hashimoto, A Time-Lapse Map of Every Nuclear Explosion Since

1945. Multimedia artwork. “2053” – This is the

number of nuclear explosions conducted in various parts of the globe.

The number excludes both tests by North Korea (October 2006 and May 2009).

-

From Wikipedia:

Muckaty Station, also known as Warlmanpa, was a pastoral lease, now Aboriginal freehold land in Australia's Northern Territory, near Tennant Creek. . . . There are seven Aboriginal groups or clans who are traditional owners of the land and dreaming sites now known as Muckaty Station (and often referred to as just "Muckaty"): Milwayi, Ngapa, Ngarrka, Wirntiku, Kurrakurraja, Walanypirri and Yapayapa.

-

From Wikipedia:

The Great Artesian Basin provides the only reliable source of freshwater through much of inland Australia. The basin is the largest and deepest artesian basin in the world, stretching over a total of 1,711,000 square kilometres (661,000 sq mi), with temperatures measured ranging from 30°C to 100°C. It underlies 23% of the continent, including most of Queensland, the south-east corner of the Northern Territory, the north-east part of South Australia, and northern New South Wales. The basin is 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) deep in places and is estimated to contain 64,900 cubic kilometres (15,600 cu mi) of groundwater.

In an e-mail response to a query about Muckaty Station and its proximity to the Great Artesian Basin (GAB), Dr. Caldicott wrote,Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory [is] where the government wants to store Australia‚’ radioactive waste but probably also foreign waste. There are aquifers underlying Muckaty station and no-one has accurately charted the extent and communication systems of the aquifers so it could well communicate with the GAB.

A map of Muckaty Station's location is shown with a drawing of the Australia's GAB:

See Also: PDF map of the GAB from www.environment.gov.au/ (local copy on ratical).

-

From Wikipedia,

The International Framework for Nuclear Energy Cooperation (IFNEC) formerly the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) began as a U.S. proposal, announced by United States Secretary of Energy Samuel Bodman on February 6, 2006, to form an international partnership to promote the use of nuclear power and close the nuclear fuel cycle in a way that reduces nuclear waste and the risk of nuclear proliferation. This proposal would divide the world into “fuel supplier nations,” which supply enriched uranium fuel and take back spent fuel, and “user nations,” which operate nuclear power plants.

-

See

Plans

for Australia to become world’s nuclear waste

dump, by Sandi Keane, Independent Australia,

18 April 2011.

Despite the Fukushima disaster, Alexander Downer has come out in support of Australia storing the world’s nuclear waste. Sandi Keane looks at the secret plans developed by John Howard and George W. Bush to turn Australia into the world’s radioactive waste dump, with healthy profits for all. Is this how Tony Abbott plans to pay for “direct action” on climate change?

-

Australia’s

New National Radioactive Waste Bill targets Muckaty

Station, on Aboriginal land by Natalie Wasley,

Antinuclear, 8 February 2012.

As pointed out in the House of Reps debate, it bears uncanny similarity to the Coalition‘s legislation it purports to replace, the main difference being it specifically targets Muckaty – a site nominated in the Howard era. Mr Wroe’s piece also ignores the ongoing opposition to the waste dump from the NT government and many Traditional Owners of the Muckaty Land Trust, who have built broad national support for their campaign and launched a federal court challenge against the nomination of the Muckaty site. If I was David’s driving instructor, I would tell him to look more carefully at the traffic signals.

-

At 19:58 minutes in Into Eternity,

Timo Seppälä (Senior Manager, Communications, Onkalo, Posiva Oy) states,

We have come to a conclusion that the bedrock, the Finnish bedrock, 1.8 billion years old, is the medium that we can predict, far to the future, at least 100,000 years ahead.

-

See the following for articles and information about what

Michael Madsen has been engaged with since talking with

Helen Caldicott:

- Film maker Michael Madsen joins the Unknown Fields Summer 2011 Trajectory from Chernobyl to Baikonur Cosmodrome

-

Unknown Fields Division Part I:

Chernobyl

Exclusion Zone An architecture report from Pripyat,

by Nelly Ben Hayoun, Domus, 3 August 2011

An international, multidisciplinary team of researchers visits the zones where the myths of the near future are manufactured -

Unknown Fields Division Part III:

Baikonur

Cosmodrome - An architecture report from Baikonur,

by Nelly Ben Hayoun, Domus, 10 August 2011

On hand for the launch of a space telescope, the UFD team completes its mission to technologically altered landscapes at the Baikonur Cosmodrome -

KNOCK KNOCK

10 November 2011, Danish Film Institute

IDFA FORUM 2011. “A cosmic documentary comedy” is the tagline for Michael Madsen's next big film project “The Visit” which takes a close look at how we humans would react if – or when – we are approached by intelligent life from outer space. According to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs the very first step in an alien emergency plan would be, quite simply, a phone call: “They have arrived.” -

VISITORS FROM OUTER SPACE

21 November 2011 | By Annemarie Hørsman | Danish Film Institute

INTERVIEW. How would we react if we were visited by aliens? Michael Madsen, who is delighted to see his award winning documentary “Into Eternity” moving into real political power forums, continues his speculative reflections in his next project which tests our imagination with a story of humanity’s encounter with alien intelligent life.