| From: |

Jim Douglass,

JFK and The Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters

Orbis Books, (Maryknoll, New York: 50th Anniversary Edition, 2013), pp. 35-37, 41-46, 220-222, 403, 404, 439. Book excerpts reproduced with the permission of Orbis Books. |

pages 35-37

In the weeks leading up to his American University address, Kennedy prepared the ground carefully for the leap of peace he planned to take. He first joined British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan in proposing to Khrushchev new high-level talks on a test ban treaty. They suggested that Moscow be the site for the talks, itself an act of trust. Khrushchev accepted.

To reinforce the seriousness of the negotiations, Kennedy decided to suspend U.S. tests in the atmosphere unilaterally. Surrounded by Cold War advisers, he reached his decision independently—without their recommendations or consultation. He knew few would support him as he went out on that limb; others might cut it down before he could get there. He announced his unilateral initiative at American University, as a way of jump-starting the test-ban negotiations.

In both speech and action, Kennedy was trying to reverse eighteen years of U.S.-Soviet polarization. He had seen U.S. belligerence toward the Russians build to the point of Pentagon pressures for preemptive strikes on the Cuban missile sites. In his decision in the spring of 1963 to turn from a demonizing Cold War theology, Kennedy knew he had few allies within his own ruling circles.

He outlined his thoughts for what he called “the peace speech” to adviser and speechwriter Sorensen, and told him to go to work. Only a handful of advisers knew anything about the project. Arthur Schlesinger, who was one of them, said, “We were asked to send our best thoughts to Ted Sorensen and to say nothing about this to anybody.”[145] On the eve of the speech, Soviet officials and White House correspondents were alerted in general terms. The speech, they were informed, would be of major importance.[146]

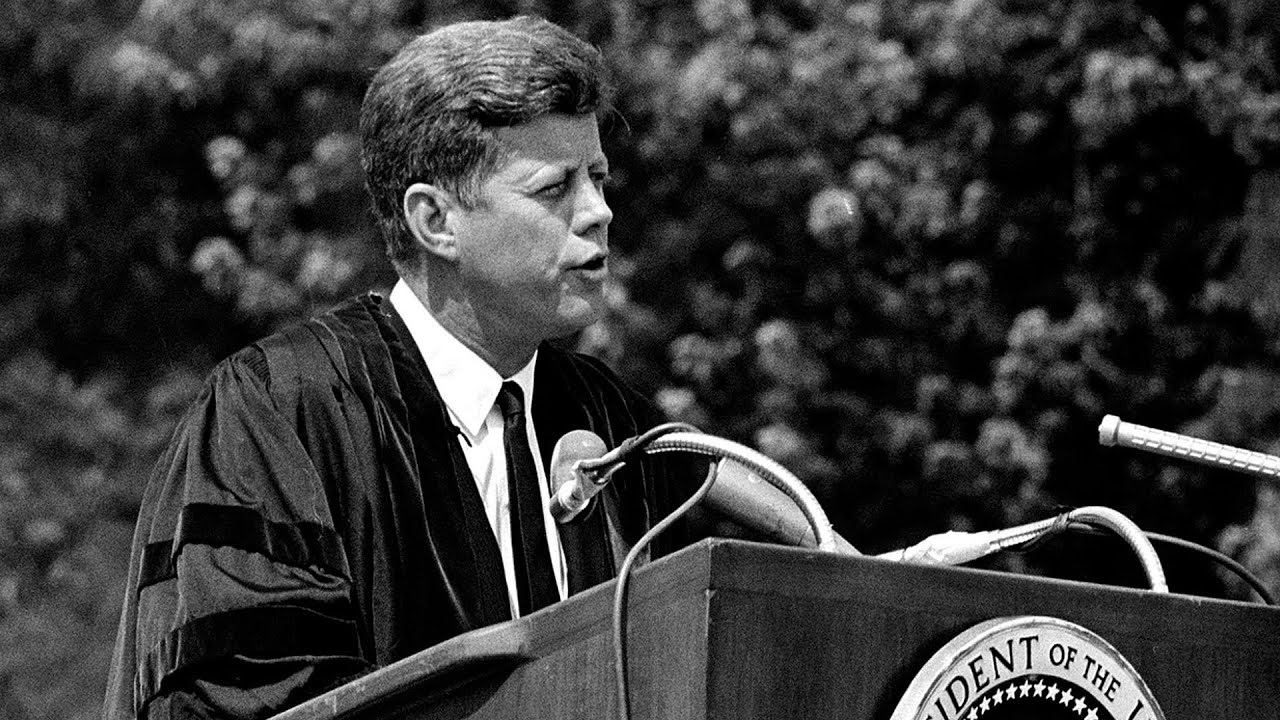

On June 10, 1963, President Kennedy introduced his subject to the graduating class at American University as “the most important topic on earth: world peace.”

“What kind of peace do I mean?” he asked, “What kind of peace do we seek?”

“Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children—not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women—not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.”

Kennedy’s rejection of “a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war” was an act of resistance to what President Eisenhower had identified in his Farewell Address as the military-industrial complex....

What Eisenhower in the final hours of his presidency revealed as the greatest threat to our democracy Kennedy in the midst of his presidency chose to resist. The military-industrial complex was totally dependent on “a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war.” That Pax Americana policed by the Pentagon was considered the system’s indispensable, hugely profitable means of containing and defeating Communism. At great risk Kennedy was rejecting the foundation of the Cold War system.

In his introduction at American University, President Kennedy noted the standard objection to the view he was opening up: What about the Russians?

“Some say that it is useless to speak of world peace or world law or world government—and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it.”

He then countered our own prejudice with what Schlesinger called “a sentence capable of revolutionizing the whole American view of the cold war”: “But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitude—as individuals and as a Nation—for our attitude is as essential as theirs.”

Kennedy’s turn here corresponds to the Gospel insight: “Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?” (Luke 6:41).

The nonviolent theme of the American University Address is that self-examination is the beginning of peace. Kennedy was proposing to the American University graduates (and the national audience behind them) that they unite this inner journey of peace with an outer journey that could transform the Cold War landscape.

“Every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward—by examining his own attitude toward the possibilities of peace, toward the Soviet Union, toward the course of the cold war and toward freedom and peace here at home.”

Thus ended Kennedy’s groundbreaking preamble, an exhortation to personal and national self-examination as the spiritually liberating way to overcome Cold War divisions and achieve “not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.” In his American University address, John Kennedy was proclaiming a way out of the Cold War and into a new human possibility.

pages 41-46

Self-examination, Kennedy said at American University, was the foundation of peace. In that speech he asked Americans to examine four basic attitudes in ourselves that were critical obstacles to peace.

“First: Let us examine our attitude toward peace itself. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable—that mankind is doomed—that we are gripped by forces we cannot control.”

I remember well the United States’ warring spirit when President Kennedy said those words. Our deeply rooted prejudice, cultivated by years of propaganda, was that peace with Communists was impossible. The dogmas in our Cold War catechism ruled out peace with the enemy: You can’t trust the Russians. Communism could undermine the very nature of freedom. One had to fight fire with fire against such an enemy. In the nuclear age, that meant being prepared to destroy the world to save it from Communism. Sophisticated analysts called it “the nuclear dilemma.”

With the acceptance of such attitudes, despair of peace was a given. Thomas Merton wrote of this Cold War mentality: “The great danger is that under the pressures of anxiety and fear, the alternation of crisis and relaxation and new crisis, the people of the world will come to accept gradually the idea of war, the idea of submission to total power, and the abdication of reason, spirit and individual conscience. The great peril of the cold war is the progressive deadening of conscience.”[167] As Kennedy observed, in such an atmosphere peace seemed impossible, as in fact it was, unless underlying attitudes changed. But how to change them?

Kennedy suggested a step-by-step way out of our despair. It corresponded in the world of diplomacy to what Gandhi had called “experiments in truth.” Kennedy said we could overcome despair by focusing “on a series of concrete actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned.” In spite of our warring ideologies, peace could become visible again by our acting in response to particular, concrete problems that stood in its way.

As JFK was learning himself from his intense dialogue with Khrushchev, the practice of seeking peace through definable goals drew one irresistibly deeper. Violent ideologies then fell away in the process of realizing peace.

“Peace need not be impracticable, and war need not be inevitable,” he said in reference to his own experience. “By defining our goal more clearly, by making it seem more manageable and less remote, we can help all peoples to see it, to draw hope from it, and to move irresistibly toward it.”

The second point in Kennedy’s theme was that self-examination was needed with respect to our opponent: “Let us examine our attitude toward the Soviet Union.” We needed to examine the root cause of our despair, namely, our attitude toward our enemy.

Kennedy cited anti-American propaganda from a Soviet military text and observed, “It is sad to read these Soviet statements—to realize the extent of the gulf between us.”

Then with his listeners’ defenses down, he brought the theme of self-examination home again: “But it is also a warning—a warning to the American people not to fall into the same trap as the Soviets, not to see only a distorted and desperate view of the other side, not to see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.”

It was a summary of our own Cold War perspective. The key question was not: What about the Russians? It was rather: What about our own attitude that can’t get beyond “What about the Russians”? The point was again not the speck in our neighbor’s eye but the log in our own.

Kennedy’s next sentence was a nonviolent distinction between a system and its people: “No government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue.” With these words President John Kennedy was echoing a theme of Pope John XXIII’s papal encyclical Pacem in Terris (“Peace on Earth”), published two months earlier on April 11, 1963.

In response to the threat of nuclear war, Pope John had issued his hopeful letter to the world just before he took leave of it. He died of cancer one week before Kennedy’s speech. In Pacem in Terris Pope John drew a careful distinction between “false philosophical teachings regarding the nature, origin and destiny of the universe and of humanity” and “historical movements that have economic, social, cultural or political ends, ... even when these movements have originated from those teachings and have drawn and still draw inspiration therefrom.” Pope John said that while such teachings remained the same, the movements arising from them underwent changes “of a profound nature.”[168]

The pope then struck down what seemed at the time to be insurmountable barriers to dialogue and collaboration with a militantly atheist opponent: “Who can deny that those movements, insofar as they conform to the dictates of right reason and are interpreters of the lawful aspirations of the human person, contain elements that are positive and deserving of approval?

“It can happen, then, that meetings for the attainment of some practical end, which formerly were deemed inopportune or unproductive, might now or in the future be considered opportune and useful.”[169]

The pope’s actions were ahead of his words. He was already in friendly communication with Nikita Khrushchev, sending him appeals for peace and religious freedom. His unofficial emissary to the Soviet premier, Norman Cousins, had delivered a Russian translation of Pacem in Terris personally to Khrushchev, even before the encyclical was issued to the rest of the world.[170] Khrushchev displayed proudly to Communist Party co-workers the papal medallion that Pope John had sent him.[171]

John Kennedy took heart from the elder John’s faith that peace was made possible through such trust and communication with an enemy. Kennedy knew from Cousins the details of his meetings with Khrushchev on behalf of Pope John. Kennedy sent along with Cousins backdoor messages of his own to the Soviet premier, as Cousins describes in his book The Improbable Triumvirate: John F. Kennedy, Pope John, Nikita Khrushchev. Something was going on here behind the scenes of Christian-Communist conflict that was breathtaking in the then-dominant context of Armageddon theologies.

So it was natural for John Kennedy to speak at American University with empathy about the suffering of the Soviet Union. “No nation in the history of battle ever suffered more than the Soviet Union suffered in the course of the Second World War,” he said. “At least 20 million lost their lives. Countless millions of homes and farms were burned or sacked. A third of the nation’s territory, including nearly two thirds of its industrial base, was turned into a wasteland—a loss equivalent to the devastation of this country east of Chicago.”

The suffering that the Russian people had already experienced was Kennedy’s backdrop for addressing the evil of nuclear war, as it would affect simultaneously the U.S., the U.S.S.R., and the rest of the world: “All we have built, all we have worked for, would be destroyed in the first 24 hours.”

“In short,” he said, “both the United States and its allies, and the Soviet Union and its allies, have a mutually deep interest in a just and genuine peace and in halting the arms race.” He added, in an ironic play on Woodrow Wilson’s slogan for entering World War I: “If we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity.”

John Kennedy, portrayed by unsympathetic writers as a man with few feelings, had broken through to the feelings of our Cold War enemy, not only the ruler Nikita Khrushchev but an entire people decimated in World War II. What about the Russians? Kennedy’s answer was that when we felt the enemy’s pain, peace was not only possible. It was necessary. It was as necessary as the life of one’s own family, seen truly for the first time. The vision that John F. Kennedy had been given was radically simple: Our side and their side were the same side.

“For, in the final analysis,” Kennedy said, summing up his vision of interdependence, “our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

If we could accept such compassion for the enemy, Kennedy’s third, most crucial appeal for self-examination could become more possible for his American audience. “Third: Let us reexamine our attitude toward the cold war, remembering that we are not engaged in a debate, seeking to pile up debating points.”

When the missile crisis was resolved, the president stringently avoided, and ordered his staff to avoid, any talk of victory or defeat concerning Khrushchev. The only victory was avoiding war. Yet for Khrushchev’s critics in the Communist world who could tolerate no retreat from the capitalist enemy, the Soviet premier had suffered a humiliating defeat. For that reason alone, Kennedy believed, there must never be another missile crisis, for it would only repeat pressures for terrible choices that had very nearly resulted in total war.

“Above all, while defending our own vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war. To adopt that kind of course in the nuclear age would be evidence only of the bankruptcy of our policy—or of a collective death-wish for the world.”

Kennedy moved on to concrete steps, already in progress, toward realizing his vision of world peace. He announced first the decision made by Macmillan, Khrushchev, and himself to hold discussions in Moscow on a test ban treaty. He then proclaimed his unilateral initiative, a suspension of atmospheric tests, with the explicit hope that it would foster trust with the enemy:

“To make clear our good faith and solemn convictions on the matter [of a comprehensive test ban treaty], I now declare that the United States does not propose to conduct nuclear tests in the atmosphere so long as other states do not do so. We will not be the first to resume.”

For those who knew the strength of will behind Kennedy’s vision, there was something either inspiring or threatening in his next statement of “our primary long-range interest”: “general and complete disarmament—designed to take place by stages, permitting parallel political developments to build the new institutions of peace which would take the place of arms.” As we shall see, Kennedy meant what he said, and U.S. intelligence agencies knew it. So did the corporate power brokers who had clashed with him the year before in the steel crisis, an overlooked chapter in the Kennedy presidency that we will explore. The military-industrial complex did not receive his swords-into-plowshares vision as good news.

In the fourth and final section of his plea for self-examination, JFK appealed to his American audience to examine the quality of life within our own borders: “Let us examine our attitude toward peace and freedom here at home ... In too many of our cities today, the peace is not secure because freedom is incomplete.”

He would say more on this subject the following night in his ground-breaking civil rights speech. On the day after President Kennedy spoke at American University, Alabama governor George Wallace let the president’s will prevail and backed away from blocking a door at the University of Alabama, allowing two black students to register. That night in a televised address to the nation, Kennedy described the suffering of black Americans under racism with a strength of feeling that recalled his compassion the day before for the Russian people in World War II:

“The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the Nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing a high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day, one-third as much chance of completing college, one-third as much chance of becoming a professional man, twice as much chance of becoming unemployed, about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year, a life expectance which is 7 years shorter, and the prospects of earning only half as much.

“We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.”[172]

In his American University address, after Kennedy identified “peace and freedom here at home” as a critical dimension of world peace, he went on to identify peace itself as a fundamental human right: “And is not peace, in the last analysis, basically a matter of human rights—the right to live out our lives without fear of devastation—the right to breathe air as nature provided it—the right of future generations to a healthy existence?”

Kennedy concluded his “peace speech” with a promise whose beginning fulfillment in the next five months would confirm his own death sentence: “Confident and unafraid, we labor on—not toward a strategy of annihilation but toward a strategy of peace.”

John Kennedy’s greatest statement of his turn toward peace was his American University address. In an ironic turn of events, the Soviet Union became its principal venue. JFK’s identification with the Russian people’s suffering penetrated their government’s defenses far more effectively than any missile could have. Sorensen described the speech’s impact on the other side of the Cold War:

“The full text of the speech was published in the Soviet press. Still more striking was the fact that it was heard as well as read throughout the U.S.S.R. After fifteen years of almost uninterrupted jamming of Western broadcasts, by means of a network of over three thousand transmitters and at an annual cost of several hundred million dollars, the Soviets jammed only one paragraph of the speech when relayed by the Voice of America in Russian (that dealing with their “baseless” claims of U.S. aims)—then did not jam any of it upon rebroadcast—and then suddenly stopped jamming all Western broadcasts, including even Russian-language newscasts on foreign affairs. Equally suddenly they agreed in Vienna to the principle of inspection by the International Atomic Energy Agency to make certain that Agency’s reactors were used for peaceful purposes. And equally suddenly the outlook for some kind of test-ban agreement turned from hopeless to hopeful.”[173]

Nikita Khrushchev was deeply moved. He told test-ban negotiator Averell Harriman that Kennedy had given “the greatest speech by any American President since Roosevelt.”[174] Khrushchev responded by proposing to Kennedy that they now consider a limited test ban encompassing the atmosphere, outer space, and water, so that the disputed question of inspections would no longer arise. He also suggested a nonaggression pact between NATO and the Warsaw Pact to create a “fresh international climate.”[175]

Kennedy’s speech was received less favorably in his own country. The New York Times reported his government’s skepticism: “Generally there was not much optimism in official Washington that the President’s conciliation address at American University would produce agreement on a test ban treaty or anything else.”[176] In contrast to the Soviet media, which were electrified by the speech, the U.S. media ignored or downplayed it. For the first time Americans had less opportunity to read and hear their president’s words than did the Russian people. A turnabout was occurring in the world on different levels. Whereas nuclear disarmament had suddenly become feasible, Kennedy’s position in his own government had become precarious. Kennedy was turning faster than was safe for a Cold War leader.

After the American University address, John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev began to act like competitors in peace. They were both turning. However, Kennedy’s rejection of Cold War politics was considered treasonous by forces in his own government. In that context, which Kennedy knew well, the American University address was a profile in courage with lethal consequences. President Kennedy’s June 10, 1963, call for an end to the Cold War, five and one-half months before his assassination, anticipates Dr. King’s courage in his April 4, 1967, Riverside Church address calling for an end to the Vietnam War, exactly one year before his assassination. Each of those transforming speeches was a prophetic statement provoking the reward a prophet traditionally receives. John Kennedy’s American University address was to his death in Dallas as Martin Luther King’s Riverside Church address was to his death in Memphis.

pages 220-222

A month and a half after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nikita Khrushchev sent John Kennedy a private letter articulating a vision of peace they could realize together.

“We believe that you will be able to receive a mandate at the next election,” Khrushchev wrote with satisfaction to the man who had been his enemy in the most dangerous confrontation in history. The Soviet leader told Kennedy hopefully, “You will be the U.S. President for six years, which would appeal to us. At our times, six years in world politics is a long period of time. ” Khrushchev believed that “during that period we could create good conditions for peaceful coexistence on earth and this would be highly appreciated by the peoples of our countries as well as by all other peoples.”[1]

Khrushchev’s son Sergei said the missile crisis had forced his father to see everything in a different light. The same was true of Kennedy. These two superpower leaders had almost incinerated millions, yet they had also turned in that spiritual darkness from fear to trust. Their year-long secret correspondence had laid the foundation. Then JFK’s appeal for help in the crisis, Nikita’s quick response, and their resulting agreement had forced them to trust each other. Sergei said, “Since he trusted the U.S. president, Father was ready for a long period of cooperation with John Kennedy.”[2]

It was during that time of hope that a conversation took place at the Vatican between Pope John XXIII and Norman Cousins, two men who were helping to mediate the Kennedy-Khrushchev dialogue that promised so much. Pope John was dying of cancer. When he and Cousins talked in the pope’s study in the spring of 1963, Pope John had just written his encyclical “Peace on Earth,” whose theme of deepening trust across ideologies was then being incarnated in the Kennedy-Khrushchev relationship. As Cousins recalled their conversation ten years later, the dying pope kept repeating a single phrase that seemed to sum up his hopeful message of peace on earth:

“Nothing is impossible.”[3]

With the help of Pope John, even Kennedy and Khrushchev had begun to believe that nothing was impossible. That was true of both good and evil. They had passed through the mutual threat of an inferno into a sense of interdependence. Through their acceptance of interdependence on the brink of nuclear war, peace had now become possible.

In the American University address, Kennedy appealed to the American people to recognize that, while the United States and the Soviet Union had differences, they were still, in the end, interdependent: “And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”[4]

Because Kennedy and Khrushchev had recognized their interdependence, nothing was impossible. After Kennedy’s peace speech, he and Khrushchev showed their determination to make peace by their remarkably quick signing of the nuclear test ban treaty—to the consternation of the president’s military, CIA, and business peers. The powers that be were heavily invested in the Cold War and had an unyielding theology of war. They believed that an atheistic, Communist enemy had to be defeated. Theirs was the opposite of Pope John’s vision that we all need to be redeemed from the evil of war itself by a process of dialogue, respect, and deepening mutual trust. The anti-communist czars of our national security state thought the only way to end the Cold War was to win it.

However, moved by the missile crisis, Kennedy and Khrushchev had turned from absolute ideologies. They had caught on to the process of peace. At least equally important was the fact that the people of both their countries had caught on. Ordinary citizens who had felt helpless during the Missile Crisis wanted more steps for peace. Khrushchev knew the Russian people were heartened by the American University address and the test ban treaty. Kennedy felt a significant shift toward peace among the American people, too, by the end of the summer of 1963.

When JFK went on a speaking tour of western states in September 1963, he discovered to his surprise that whenever he strayed from his theme of conservation to mention the test ban treaty, the crowds responded with ovations. He found that his beginning steps toward peace with Khrushchev had become popular in areas normally identified as bastions of the Cold War. When he spoke at the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, usually considered the heart of conservatism, he was greeted by a five-minute standing ovation.[5] Intrigued White House correspondents suggested to Press Secretary Pierre Salinger that the president was suddenly tapping the public’s newfound desire for peace. Salinger agreed. “We’ve found that peace is an issue,” he said.[6] Kennedy realized from his trip west that he could make peace much more of an election issue than he had thought.

Moreover, he now had a secret political partner in Khrushchev, who had admitted in their correspondence that a second JFK term as president “would appeal to us.” Not quite one of the six years Khrushchev said he hoped to work with Kennedy “for peaceful coexistence on earth” had passed. They had made good progress. Nothing was impossible in the five years remaining in Khrushchev’s hoped-for time line for their joint peacemaking.

Following the president’s successful grassroots organizing with Norman Cousins for Senate ratification of the test ban treaty, the hope for peace was becoming contagious. Kennedy realized from both Khrushchev’s readiness to negotiate and the public’s support of the test ban treaty that a peaceful resolution of the Cold War was in sight. Nothing was impossible.

To the power brokers of the system that Kennedy ostensibly presided over, his and Khrushchev’s turn toward peace was, however, a profound threat. The president’s growing connection with the electorate on peace only increased the threat, making JFK’s reelection a foregone conclusion. As the Cold War elite knew, Kennedy was already preparing to withdraw from Vietnam. They feared he would soon be able to carry out a U.S. withdrawal from the war with public support, as one part of a wider peacemaking venture with Khrushchev (and perhaps even Castro).

For people of great power in the Cold War, everything seemed to be at stake. From the standpoint of their threatened power and what they had to do, they, too, thought that nothing was impossible.

- ↩ Merton, Cold War Letters, pp. 47-48

- ↩ Pope John XIII, Pacem in Terris (New York: America Press, 1963), p. 50.

- ↩ Ibid., pp. 50-51.

- ↩ Norman Cousins, The Improbable Triumvirate: John F. Kennedy, Pope John, Nikita Khrushchev (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), pp. 80, 91.

- ↩ Ibid., p.108.

- ↩ Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963, pp. 468-69.

- ↩ Sorensen, Kennedy, p. 733.

- ↩ Schlesinger, Thousand Days, p. 904.

- ↩ Ibid., pp.904-5.

- ↩ Max Frankel, “Harriman to Lead Test-Ban Mission to Soviet [Union] in July,” New York Times (June 12, 1963), p. 1.

- ↩ “Message From Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy,” December 11, 1962. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume VI: Kennedy-Khrushchev Exchanges (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996), p. 228.

- ↩ Sergei N. Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), p. 695.

- ↩ Norman Cousins, “Pope John’s Optimism on Peace: Nothing Is Impossible,” Seattle Times (April 1, 1973).

- ↩ Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963 (Washington: U.S. Govern- ment Printing Office, 1964), p. 462.

- ↩ David Halberstam, The Best and the Brightest (New York: Random House, 1972), pp. 295-96.

- ↩ Ibid., p. 296.