| [0:00:10] | Ratcliffe: We’re here today on August 5th, 1993, with Colonel L. Fletcher Prouty, Air Force-retired, to discuss various incidents in history that were so formative in post-World War II, U.S. history, politics, power, and to look at things in more detail than is commonly done throughout the media in this day and age. | ||||

| April 1961: The Bay of Pigs Invasion | |||||

| One thing that I’ve always felt you provide a great deal of solid information on that is never discussed is the whole formative event of the Kennedy administration, which is the Bay of Pigs, and citing the Letter To The President that was written by the four people that he convened to study what went wrong with the Bay of Pigs. | |||||

| [0:01:16] | There’s a great deal in that committee, the testimony that they heard from people, the way they operated, that is never talked about, that is crucial, it seems, to understanding how Kennedy got his sea legs, so to speak, when he became president, in seeing how things weren’t working right with the failure of this operation. I’d like to have you tell us some about—perhaps start with this final report that was never found for years, because people were asking the wrong questions, that indicates the perceptiveness of the President in trying to understand what had really happened, so that it wouldn’t happen again. | ||||

| [0:01:59] | Prouty: It’s an awfully good approach to the problem, because very few people have studied the Kennedy period before his death, or even have known much about Kennedy before he was elected president. He came right out of World War II with a busy career during the war as a naval officer. He was elected congressman from Massachusetts, served as a congressman. He stayed here in Washington, served as a senator from Massachusetts, and then was elected president. There were very few men arriving at the office of president who had more background in Washington than Kennedy had. He was younger than most of them, but he had more background experience, which means he knew the bad things as well as the good things. | ||||

| [0:02:45] | There were a lot of things that he was against in the way the government had been going under the Eisenhower and post-war administration, and he wanted to use the presidential power to change them. And one of the first things that he found that he had to take care of—there were two things, was the Bay of Pigs. Now, that was an Eisenhower program that was approved by the Eisenhower National Security Council in March of 1960. About May of 1960, the CIA people came to my office, because it was my job in the Pentagon to provide the support of CIA’s clandestine operations. That was my job, I had been in the job for years. And they wanted to have the military open a base where they could train these exile Cubans who were perfectly willing to try to get back into Cuba and incite enough rebellion to throw Castro out, because that’s what the original Eisenhower approval was, to try to get Cuban support for the plan. Eisenhower would never have approved an invasion. He never did. Eisenhower knew too much about invasions to have that happen. | ||||

| [0:04:05] | Well, you follow that through now from the mid-’60, and then you have this important event when Kennedy and Nixon had the TV debates just before the election. And everybody felt that the two were just inseparable, there was no way to tell who was going to be elected president. And they came to debate number four, and Kennedy pressed the Cuban issue, the Castro issue, because Nixon had made so much of it, that the government—"We would overthrow Castro. Got to get rid of Castro. He’s a communist." And all that sort of thing. And Kennedy, who knew as much or more about the program than even Nixon did, whooped Nixon in the debate. | ||||

| [0:04:51] | And let me tell you just a little personal incident as a part of my official duties, but it lets you see the validity of this, I was asked to go to the Senate office building to a certain room number, and to pick up four men and bring them back to the Office of the Secretary of Defense. That’s where I was working, I was working with the Office of Secretary of Defense. The four men I picked up were the leaders of the Cuban program, Artima, and Mendonca, and Deborona, and those people. And they knew Kennedy, the office room I was sent to was Kennedy’s office. So here’s Kennedy with these Cubans talking with them in August of 1960. He had just been—won the Democratic nomination to run for president, he knew this background. | ||||

| [0:05:38] |

And furthermore, I understand that the Cubans had visited him in his home in Palm Beach. He knew these people, he knew everything that was going on. Well, Nixon didn’t know he knew that. So in the debate, when it came time to argue with Nixon about it, Kennedy cleaned up on that debate, and a lot of people believed that’s how he won the election, a very narrow election, but he won.

Days after that debate, the CIA came to us in the Pentagon talking about an invasion of Cuba. That was not the approved plan. Kennedy was not president yet. We knew Eisenhower wouldn’t talk about that, the CIA did it, they put pressure on Kennedy themselves. And what had been a plan to drop 30 men groups from an airplane, a C-46 can carry about 30 with their equipment, or over the beach program from submarines or fast boats, 20 or 30 men. All of a sudden, they’re talking about 3,000 men, training the 3,000. I had to send men to Guatemala to train pilots. I had to get aircrafts reconfigured in Arizona to be used for that purpose. We got Filipino experienced men that General Lansdale knew that helped him during the time when he was in the overthrow of Quirino in the Philippines, which is much like the Castro thing. So the Filipino experience was valuable. People don’t realize how big the Cuban program was. The ships had arms and equipment on board enough for 25,000 fighters. Not just the 1,500 that went on the beach. You see, all of this developed in the working arrangements that were being made from day-to-day to support this operation. But the strange thing was how it accelerated right after the election. They were going to press Kennedy to accept the invasion, because during the time, before his inaugural, they got all of this change started and in being. So that by the time of the invasion, actually, the ships were at sea from different areas already heading for Cuba, and Kennedy had not approved the program. |

||||

| [0:07:49] | So you see, that is so different from what most people have heard about the way the thing was organized. One thing that the agency had done at the suggestion of the JCS was to bring in a most competent marine colonel who knew invasion tactics to work out the invasion plan. The JCS had told the CIA that if Castro’s combat aircraft were not destroyed before the men hit the beach, there was no chance that they could get on, because the combat aircraft being on homeground and all, and the men just on the beach with no protection, couldn’t protect themselves. They must destroy the aircraft totally before the men hit the beach. That was a fundament of the whole plan. The marine colonel knew it, and the JCS had told the CIA that. | ||||

| [0:08:39] | Well, it finally came down to where after several meetings with the President, during which he would not approve the program, finally, in the middle of April of 1961, Mr. Dulles told him that, "Well, we have got to do something. We’ve been training these men now for a year. They think they’re going to be brought into their home, and they think we’re going to help them gain their country back again. And incidentally, the ships with the men on board are at sea rendezvousing around the Vieques Island area, we must get an approval to go. Is there anything else to keep it from going?" Kennedy waited for the strike on the airfields of Cuba until Saturday morning. They destroyed seven of Castro’s 10 combat-capable aircraft. They didn’t have to bother with the transports and all, they went after the bombers and the fighters. They destroyed seven of them. | ||||

| [0:09:40] | Unfortunately, three jets had taken off from where they had been the day before when we had pictures of them, and gone down to Santiago for the weekend, and they weren’t there, and they weren’t destroyed. So on Sunday, when they went to brief the President, they told him, they showed him pictures, they had destroyed seven planes, but three were left. They had to get those three airplanes before the men hit the beach at Zapata landing. Well, Kennedy ordered specifically, sometime about mid-afternoon, 3:00 in the afternoon, he ordered the first thing to be the destruction of those aircraft. That was a Kennedy order. | ||||

| [0:10:20] | A very close friend of mine was in command of the bomber base in Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, that was to do the job. Four B-26s were to be dispatched about 1:00, and it’s very important, because they had to hit the planes before the dawn landing of the men on the beach, or the landing would—they’re going to be in the air supporting the beach, and they were so superior to the bombers that they shoot the bombers down, one after the other. Everybody understood that, we thought. | ||||

| Post Mortem: The Cuban Study Group | |||||

| [0:10:51] | So Kennedy ordered that, and as a prerequisite to the landing, he agreed to the landing on Monday morning, April 18th, 1961. Now, when there was a study of what happened, Kennedy put together the Cuban Study Group to find out what went wrong. Here is an old mimeograph copy from my days in the Pentagon of the report of this Study Group. It wasn’t seen by anyone, or very few people, for at least 20 years when it began to pop up in books, that people knew about it. And then finally, in 1981, this book was published for academic purposes for university use, book called [Operation] Zapata, which is every word that’s in here, just an absolute copy of this. But this is the old original. I want you to see what it looked like in the beginning. | ||||

| [0:11:50] | And when the Cuban Study Group questioned the people that came before as to what happened, and why didn’t we succeed with the Bay of Pigs program, they ran into a most interesting situation, because first of all, Kennedy and his advisors were very adept at this organization. They really did a good job. Can you imagine a committee better than this one to study the Bay of Pigs? Allen Dulles was on that Study Group. Admiral Burke was on the Study Group. Admiral Burke was the CNO of the Navy, member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and he was the one who had been designated to support the operation of the Bay of Pigs landings. Now, he knew more about it than anybody else. You’d sit in the room, no matter who came in, Admiral Burke, or Arleigh Burke, knew what was going on. And I’ve talked to him many times since then about this, and he did know. | ||||

| [0:12:46] | Another man was General Maxwell Taylor. Maxwell Taylor and Kennedy had never met, but Kennedy knew Maxwell Taylor’s reputation, and he knew that he was a good, solid man for this kind of investigation. So he put Maxwell Taylor as the chairman of the group. But there was a fourth man, and as my friends would tell me when they’d come back from the hearing, I knew almost all the guys that went in there, my office was only about two doors down from where the committee was meeting in the Pentagon, they’d come back and they’d say, "You know, those three guys are pretty tough, but it’s that little son of a gun on that straight back chair in a corner that’s really watching it with BDI. It doesn’t say anything." Well, that’s Bobby Kennedy. Can you imagine? Bobby Kennedy, Maxwell Taylor, Arleigh Burke, and Allen Dulles, to study what went wrong with the Bay of Pigs. | ||||

| [0:13:37] | Now, they were even sharper than that, because by that time, Maxwell Taylor and my boss, General Lemnitzer, and Arleigh Burke had made up their mind that this was the last time that the CIA was going to get into a major operation. They weren’t the right people to be running military type operations. So they brought in other competent people to provide them with information that they would provide to Kennedy in this report. And one of the best things they did, one of the people they brought in that was really important, was General Walter Bedell Smith. Now, people who remember World War II will remember that he was the Chief of Staff for Eisenhower for the invasion of Europe, and the whole European operation of World War II. A very competent, experienced, reliable general. | ||||

| [0:14:33] | Immediately, at the end of World War II, Walter Bedell Smith had been sent to Moscow as the American ambassador to the Soviet Union. Well, of course, they were our partners through the war. It was a very friendly relationship. Smith was highly regarded by the Soviets as a general that had helped them defeat Hitler and his German troops. So it was a great assignment for Smith. He learned a hell of a lot from that. And so what did he do? From Moscow, he was assigned to the new Central Intelligence Agency, and he became the Director of Central Intelligence. A lot of people don’t remember that. | ||||

| [0:15:10] | Ratcliffe: Under Truman. | ||||

| [0:15:11] | Prouty: Under Truman, yes. And as the Director of Central Intelligence, all the CIA people knew him very well. They knew that he knew things, they knew he was tough, and that they couldn’t get around him. So what did they do in the Zapata program? They bring General Smith in. He didn’t have anything to do with the Cuban program, but he was pretty useful, because among other things, and this probably tips Kennedy’s hand as close as anything I can think of in trying to study what happened, why was Kennedy killed? What brought up the pressures, and the power, and the intense feelings against Kennedy that would cause people in power to make the decision to get rid of him? | ||||

| [0:15:59] |

It begins with this sort of a thing. In response to questions about running something like the Bay of Pigs, Smith said, "[Clearly,] A democracy cannot wage war. When you go to war, you pass a law giving extraordinary powers to the president. The people of our country assume when the emergency’s over that the rights and the powers that were temporarily delegated to the chief executive will be returned to the state, to the counties, to the people." Pretty fundamental statement from a major—a full general, but from a major general, an important man.

He went on to say now about Bay of Pigs, "I only know what the papers say, but covert operations," and he knew a lot about them, he’d been the DCI, "can be done up to a certain size, and we’ve handled some pretty large operations." By that, he meant if it’s not more than 2 or 3 people, it can’t be a secret anymore. In fact, the New York Times had carried front page headlines saying the U.S. government was supporting the exiles against Castro in March of 1961. It was already all over the papers. He’s pointing that out as a mistake. |

||||

| [0:17:20] | But then Smith begins to get to the point. He said, "I think that so much publicity has been given to CIA that the covert work might have to be put under another roof." He was pretty explicit about that. He’d say, "It’s time we take the bucket of slop, and go out and cover over it." Well, what something like that does is put in the President’s mind the words from a man that knew everything there was. | ||||

| June 1961: National Security Action Memorandum No. 55 | |||||

| From the time he heard that from Walter Bedell Smith by way of his Cuban Study Group committee, you know he had one thing in his mind: he’s going to get through with the CIA in that kind of business. And let me just read you what General Smith—excuse me, General Taylor presented to the general when that was over. He accepted a paper that was called NSAM—if I can find my papers here—Number 55. | |||||

| [0:18:35] | Ratcliffe: Kennedy accepted a paper, or— | ||||

| [0:18:37] | Prouty: He accepted the paper from the group, from Maxwell Taylor. I thought I had it right here. Sorry. You’re going to have to edit this a little bit. I had it right in front of me here a minute ago. | ||||

| [0:18:50] | Ratcliffe: It wasn’t the blue tag? | ||||

| [0:18:55] | Prouty: No. Darn it all. I’m sorry. Oh, here it is. When the Cuban Study Group had completed its work, they had agreed unanimously with their own report. Even though Dulles was on there, it was a unanimous vote. Even though Bobby Kennedy was on it, it was a unanimous vote. It ended up as a Letter To The President on the 13th of June, 1961. Their work was done very quickly. And one of the dominant things to come out of it was a paper [titled National Security Action Memorandum 55] that President Kennedy signed personally, and sent directly to General Lemnitzer, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He didn’t send it to the State Department, to Dean Rusk. He didn’t even send it to McNamara which all correspondence ordinarily would go through, and he didn’t send a copy to CIA. So you can see that Kennedy was saying to General Lemnitzer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, "This is what I want done." Now, in the procedures of how you do these things in the Joint Staff, where everything is very formal, it just happened that I was the officer that the Director of the Joint Staff gave this paper to from the White House, and said, "Prepare a briefing for the chiefs." And I did, so I’m very familiar with it. | ||||

| [0:20:23] | I’ll only read a paragraph, but you don’t have to read more: the President informed the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the president regards the Joint Chiefs of Staff as his principal military advisor responsible both for initiating advice to him and for responding to requests for advice. He expects their advice to come to him direct and unfiltered. And that the “Joint Chiefs of Staff have a similar responsibility for the defense of the nation in the Cold War as in conventional hostilities.” Now, in the terminology of the government, to say that the Joint Chiefs of Staff have that responsibility in the Cold War, he’s saying the CIA will no longer have that responsibility. You see? | ||||

| [0:21:20] | That was a stroke of the pen that was as powerful as a thunderclap. And when I read that to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, you could have heard a pin drop. And I was told, "Colonel Prouty, take that back to the files. When we need it, we’ll call you." You know what that meant? They were going to wait until the situation had been completely prepared for this next step forward, because that’s a major change. How can— | ||||

| [0:21:52] | Ratcliffe: They understood the implications. | ||||

| [0:21:54] |

Prouty: Yes. They realized, how can the military in uniform go into covert operations? I mean, the ridiculous POW/MIA situation that we have now is a result of that. 15 years of the Vietnam War, everybody that went to Vietnam was under the command operational control of a CIA man. Well, then how can he be a prisoner of war? He’s a spy. And that’s what the enemy thought. They didn’t have a darn about all the fine print.

So you see, the chiefs of staff knew that. So for the next few years, Kennedy studied this situation and prepared the ground for a report. But this is why I feel that the key, the beginning point, and the troubles that Kennedy had with many points of power began with this situation, because he signaled clearly, with the assistance of General Smith and the others, that he was putting the CIA out of this business, and turning them back to intelligence only. And of course, the law that created CIA never gave him this authority in the first place. So he was right, and he knew that law. That’s why I say the Bay of Pigs is the key to the problems that came later. |

||||

| McGeorge Bundy and the Bay Of Pigs Failure | |||||

| [0:23:05] | Ratcliffe: One other thing in that is the question of the miscommunications apparently that occurred come Sunday afternoon, Sunday evening that seems to have centered around McGeorge Bundy, his special assistant. | ||||

| [0:23:20] | Prouty: Yes. There is a common misunderstanding about that business. Among the people called before this Cuban Study Group, the four men that I mentioned to you, was the advisor to the President, Mr. McGeorge Bundy. And he, I believe, visited them three times, and they also accepted written material from him. It was a pretty thorough contact between the committee and Mr. Bundy. And then in their conclusions, which anybody can read, they pointed out that it was their opinion that the most significant reason for the failure of the Bay of Pigs was the fact that this airstrike that Kennedy had ordered on that Sunday afternoon, the day before the landing, was canceled. And in pursuing how that happened, they found out that at 9:30 on Sunday night, McGeorge Bundy had called General Cabell, who was responsible for the CIA at that time, because of all weekends, Allen Dulles was out of the country. Here he is in charge of the whole thing, and Allen Dulles was out of the country. | ||||

| [0:24:33] | But anyway, General Cabell, perfectly competent person, was called by McGeorge Bundy, and told not to fly the airplanes that night until they could operate the next day off the beach at the Zapata landing site, which destroyed the whole operation. If McGeorge Bundy had had a little more military experience perhaps, or if General Cabell had just a little more—thought about it more, they’d have realized that they absolutely destroyed the Bay of Pigs there, because if they didn’t destroy those last three aircraft, they were going to lose. And those three aircraft, the first thing in the morning, sank two supply ships. So that the men on the beach had no ammunition, their food was gone, their radios were gone, their trucks were gone, everything, just those little airplanes did it. | ||||

| [0:25:27] | And during the period that the men were on the beach, they destroyed 16 B-26s. In other words, just raised havoc with the whole operation. So it’s obvious the Study Group, when Maxwell Taylor wrote his Letter To The President, he said, Our conclusion is that the principal reason for the failure was the failure to carry out the mission that the President had ordered to destroy those last three planes. | ||||

| [0:25:55] | Ratcliffe: Why did Bundy give that call? | ||||

| [0:25:59] | Prouty: There have been a lot of collateral points. The paper I’ve read to you does not elaborate on why he did it, but with Bobby Kennedy in the room, you know very well that Bundy couldn’t say such other things as, "Oh, the president told me to do it." | ||||

| [0:26:19] | Ratcliffe: Right. | ||||

| [0:26:19] | Prouty: Because Bobby would have known that wasn’t true. | ||||

| [0:26:21] | Ratcliffe: Right. | ||||

| [0:26:21] | Prouty: So he couldn’t say that. And they didn’t press him to other things, except there was a collateral problem. Adlai Stevenson, who was our ambassador to the UN, had been seriously hurt by the fact that on the Saturday morning strikes, the CIA’s cover story said that the planes were flown by Cuban Air Force people themselves in Cuban planes, and they’re the ones that bombed the site, not the exile group. And there was a big picture in the front of the paper that Adlai Stevenson held up in the UN, and said, "See, these are Cuban planes painted with Cuban [inaudible 00:27:05]. These are Cuban pilots. They want to get rid of Castro." All the Cuban delegates at the UN went up and took a little picture and said, "Look, there’s eight guns sticking out of the nose of those B-26s. We don’t have anything like that. That’s your airplane." Blew it. Well, that embarrassed Stevenson so bad that you couldn’t talk to him about the invasion. | ||||

| [0:27:24] | And we feel that from the discussion between Stevenson and Rusk—Rusk was always rather cool to this operation in first place, and Bundy, that based upon Stevenson’s intense feelings, and perhaps Bundy’s inexperience in military matters, I don’t know, I couldn’t make an excuse, all I know is he called Cabell and said, "Don’t fly it." And that’s on the record. I don’t say that. I read it from the record. | ||||

| [0:27:53] | Ratcliffe: Because there’s the place that we put the yellow Post-It in there that was the actual base conclusion of their sense of why it had failed, which is never talked about. This is never articulated anywhere in newspapers or anything, if the Bay of Pigs is ever discussed. | ||||

| [0:28:11] |

Prouty: That’s a problem too, because there are many books written about the Bay of Pigs, and some of them were written after 1981 when Zapata had been released. Up to that time, this kind of thing was not available. I had it, but I don’t know anybody else had it. They have never quoted the exact words, and to be sure that we understand exactly what the Study Group found, I will read you the words that they sent to the President. It’s 43 in their report, and it simply says, "At about 9:30 PM on 16 April," that was that Sunday when Kennedy directed the attack, "Mr. McGeorge Bundy, special assistant to the President, telephoned General C.P. Cabell of the CIA," who was the Deputy Director of CIA, and had a long time experience with CIA, "to inform him that the dawn airstrikes the following morning should not be launched until they could be conducted from a strip within the beachhead."

Now, you see, there was a strip within a beachhead, but you can’t destroy the airplanes after they’ve already destroyed your landing. I mean, it’s backwards. And this hit the committee. I mean, this is the thing they said, this is our finding as the basic reason for the failure of the Bay of Pigs. And when they interviewed Cubans down through here in the back, when they talked to these poor Cubans that were involved, each of the Cubans, one after the other says, "The problem was we didn’t have the aircraft to destroy those last three." And of course, certain propagandists or whatever you want, revisionists want to say that the problem was that Kennedy denied the air cover. |

||||

| [0:30:01] | There was no air cover in the plan because the plan was written and approved by the JCS to destroy all of Castro’s aircraft first. You don’t need aircraft if they had no planes. See, the plan was built on that idea. And people say that he should have provided the air cover. There is a National Security Council directive, which is a superior document to everything we have in the executive department, that was produced and signed in Eisenhower’s time in March of 1954, ’54. It had been in effect for a long time, called NSC Directive number 5412. | ||||

| [0:30:48] | And that directive prohibits the use of uniformed services in covert operations, prohibits it. Our government knew that during Eisenhower’s time, and of course Kennedy knew that during his time. That precluded the use of military in a clandestine operation. And that’s the kind of thing that General Smith was referring to. You can’t mix the two. You can’t put the military in covert operations. | ||||

| [0:31:16] | And we’re having trouble with that today. Is our operation in Somalia—is that considered maybe a covert operation or is it a military operation? How are we running? Are the people that are flying the airplanes considered military or are they considered some kind—we don’t have a place in the middle of those. This is what the government’s trying to work out at the present time. What is the role of the military? Even in the Vietnam War for 15 years, the military that were used before 1965—and it started in 1945—the first American was killed in Vietnam in September ’45. For those 20 years, all activity was covert. It was under the CIA. | ||||

| [0:31:58] | So that’s what we’re going back to the program here. And Kennedy knew that it was against the government policy to use military active duty air crews in such a landing as a covert operation, because immediately it would reveal the hand of the US government in an operation against a sovereign country, and that’s not permitted. | ||||

| [0:32:20] | So the people that throw the idea of Kennedy’s failure to provide air cover are just unaware of the situation that existed legally, in practice, and in the way you use military in this country. We agree with those laws and international agreements, and we don’t do it the other way. | ||||

| Bay Of Pigs and Vietnam: Major CIA Operations | |||||

| [0:32:42] | Ratcliffe: Except, of course, leading from the near to the far from the Bay of Pigs to Vietnam. By the early ’60s, we had already been there in a capacity since 1945, and it was still under the heading of Covert Operations. CI was in control. And as the Kennedy years started to happen, by the time we get to 1963, ind the summer of ’63, his own decision to try and actually deal with this thing that was clearly for him becoming more and more confused, mismanaged, wasn’t sure what was happening there. | ||||

| [0:33:22] | And we come to this marvelous GPO documents published from August to December of ’63, charting his approach to actually trying to deal with something that had been on his mind. But it hadn’t been on his mind as much in ’61 or 2 as other things that he was trying to manage like Bay of Pigs, which was also launched before his inauguration, as far as the real impetus for the original plan. And then that plan turned into an invasion after Eisenhower was effectively lame ducked from the election. | ||||

| [0:33:54] | This government printing office set of documents is fascinating to me in terms of its indicating, and especially you were working with Krulak, who was drafting so many, or involved in so many of these meetings, that he was trying to find a way to really bring us out of a completely untenable situation. | ||||

| [0:34:12] | Prouty: You see, that’s a good way to link the two together because historically, these two things ran together. They were essentially the same thing. They were major CIA operations that the generals knew were too big to even be thought of as covert operations. The CIA assisted a rebellion in Indonesia in 1958, in which at one time, I myself ordered the delivery of 42,000 rifles. I mean, that’s not a covert operation, you see. We were using submarines against the south coast of the islands of Indonesia, not a covert operation. | ||||

| [0:34:51] | So the military looked very carefully at these things and knew that the CIA was going much too far. We supported the Khampa people in Tibet, something like 60 or 70,000 of them, by dropping arms to them, medicine, weapons, everything to those people. That’s not covert, but we thought it was. We put it under the rules of CIA’s operation. And this is what Kennedy was facing during that transition from the Eisenhower time when the CIA had begun to get into all these things. The Indonesian rebellion, the Tibetan program, the Cuban program all were in that period of time, and Kennedy inherited that. | ||||

| [0:35:31] | And at the same time, the general, General Ridgway, who died just a week or two ago, told Kennedy clearly, "Don’t ever let Americans come into Asia. Don’t ever bring American soldiers into Asia." And General Bradley, I used to be General Bradley’s personal pilot, and I know the gentleman, one of the finest men ever put a uniform on, he gave Kennedy the same answers. Eisenhower, in this book here on the Foreign Relations of the United States says how bitterly he opposes the entry of American divisions into Vietnam. If I’ve tabbed that page, it’s very interesting. | ||||

| October 1963: National Security Action Memorandum No. 263 | |||||

| [0:36:19] | This, by the way, is the Foreign Relations of the United States, Vietnam, August-December 1963, zeroing right in on the peak of the time of Kennedy’s involvement in the planning for the future in Vietnam. And anybody that wants to think that Kennedy was not deep into the activities in Vietnam, doesn’t realize that during this period of that time, there were meetings going on day after day after day in the White House, in which my own boss, General Victor Krulak was involved, Maxwell Taylor was involved, McNamara was involved. | ||||

| [0:37:00] | And what that would mean is when they’d come back to the office, the rest of us and the Joint Staff were involved supporting the President in the development of these plans. Because he knew that he was going to have to make the decision, as he did in NSAM 55, to get the CIA out of this covert work. And with the CIA out of, say, the operation in Vietnam, he saw no role for the military. And it was perfectly logical from the Kennedy point of view and from what the Joint Chiefs of Staff had told him that we should not be in Vietnam. | ||||

| [0:37:36] | When he wrote this document, which because of our movie, JFK, Oliver Stone’s work, where we introduced the subject of the National Security Action Memorandum Number 263, which was written and signed on October 11th, 1963, saying that all American personnel would be out of Vietnam by the end of ’65. That was Kennedy’s decision after all of this work spanning this period of six months. And here you can read day by day by day, the meetings were—well, I counted over 50 meetings that are listed in this book in which my own boss, General Krulak, attending meetings with President Kennedy on Vietnam. | ||||

| [0:38:26] | And as Kennedy worked his Vietnam policy out during that period, he arrived at what you might call a scenario. He wanted to be sure everybody understood what he was doing. So he sent General Krulak quickly to Vietnam, the idea being published in the papers that he was going to get the last minute word in Vietnam to see how things stood. | ||||

| [0:38:51] | Ratcliffe: That was in late August or— | ||||

| [0:38:53] | Prouty: Late August. I think he actually traveled in September because I myself was sent to the CINCPAC headquarters in Hawaii to meet with Admiral Felt, and I have yet never revealed the reasons for that meeting, but the two had a very strong—I was doing a lot of writing for General Krulak and they were very much related. And when General Krulak came back, he met with Kennedy and discussed up to date the things he heard from the people out there, which of course we knew by telephone anyway, but it made the scenario more reasonable. | ||||

| [0:39:23] | And so immediately, Kennedy ordered Maxwell Taylor and McNamara to go to Vietnam. And so they went late in September, I believe it is. After a very busy flying trip, going all over the country, and talking not only to President Diam, but to his opposition, because by that time Diam had some serious opposition in his country, they came back. | ||||

| [0:39:51] | Well, they had brought a big trip report for the President. Now, it’s absolute fantasy to think that two busy men like General Taylor and Mr. McNamara are going to make a quick flying trip all through Vietnam, transverse in the Pacific Ocean and everything and write a great trip report while they go. It would be written right in the Pentagon, but more importantly, it was being written as a result of these meetings. | ||||

| [0:40:20] | And Kennedy was dictating the policy daily to these people that he met with. His staff in the White House, people from State Department, the people from CIA and the military. And when McNamara and Taylor got back to Hawaii, a jet carrying the report, landed in Hawaii and gave it to hi a big document with leather covered, with President John F. Kennedy on the cover and all that sort of thing. They couldn’t possibly have done that while they were traveling. | ||||

| [0:40:52] | And then they had the time to review the report as they flew back to Washington, usually an eight hour, 45 minute trip in those days in one of the Air Force One aircraft. And they left Andrew’s field in a helicopter. They arrived on a White House lawn and presented it to the President. They had just left him about two days earlier and here was the trip report. That’s October 2nd of 1963. And that Trip Report contains the information that Kennedy had approved that he was going to bring a thousand men home by Christmas time, that’s a thousand military men. And by the end of ’65, the bulk of US personnel. | ||||

| [0:41:38] | Now, bureaucracy is an interesting thing. We learn what certain words mean. If he had said he would bring home the bulk of American military personnel, you would assume that the military personnel were there. So he’d bring them in. And most people who write about that period say Kennedy was going to bring home or not bring home—they used the word that we’re going to withdraw the soldiers. | ||||

| [0:42:06] | Well, they weren’t going to withdraw them. They weren’t there. Withdraw is not the word. That’s wrong. And many people have been writing for the Nation magazine and other magazines like that trying to explain Kennedy’s mind, overlooked the fact that we very carefully inserted into that document, "Bring home the US personnel." And what did that mean? The CIA people were coming out. So again, that lowered the boom on the CIA, and this time it was the last time. They were going to be out of covert operation completely. So NSAM 55 began the movement of getting CIA out and 263 closed the book on it, and by ’65, he would have had no CIA people in Vietnam at all. And they’d been there since ’45. So you see a good long period of time, 20 years. | ||||

| [0:42:52] | And in other countries too, he would have stopped them from being in covert operations overseas. They’re very fundamental points that if you look in the right books and at the right reports, you get them all and they’re all backed up. These are not my words. I happen to be there and I have to be working in them, but this series, especially this latest book that had just been released, gives you the answers to what people have been looking for for years. But the trouble is that during this period, countless history books have been written about Kennedy, about Vietnam, about the post-war period, about the Cold War. And the writers have not used this sort of material. And unfortunately, the books are, what would we call them? Fantasy or mythology. | ||||

| [0:43:39] | Ratcliffe: Concoction? | ||||

| [0:43:39] | Prouty: They’re incorrect. I belong to the Society of Historians for American Foreign Relations, a wonderful organization of thousands of mostly history professors all throughout the country. And as we have our annual meetings, one of the complaints that arises more frequently than any other is the quality of history books today. Quality meaning are they true? Are they revisionist? There’s more things been written about Kennedy that are absolutely untrue since his death. There’s no sense in killing a guy twice, once with a gun and once with a typewriter, and they’re untrue. | ||||

| [0:44:21] | And what I think people ought to do is refer to the work of these generals, like this report at the Bay of Pigs, or refer to these works, papers from the State Department. They are listed as The Foreign Relations of the United States, and see what the facts are. Or refer to some of the gentlemen that are mentioned in here who are still with us, God bless them, because those are the important things, and that tells us what really happened. | ||||

| [0:44:45] | And this is why when I worked with Oliver Stone, we were working from this kind of paper, and that’s what stirred up so much opposition. Because when these big time writers in the New York Times and the Washington Post and other papers said, "There is no substantive history to back up what Stone’s putting in the film," all they need to do is read these books. There’s the substantive history. And it’s appalling to think that these men who work every day on the minds of the American public with their computer writing through the New York Times and the Washington Post and the rest of them are telling us that sort of thing when they know very well what they’re saying is not true. It’s too bad, but it’s not true. | ||||

| [0:45:30] | Ratcliffe: And as you were saying before, the Taylor McNamara report, which became, in essence, the formalized text for 263, you were involved, working under Krulak, in writing a lot of what became their report that they gave back to Kennedy when they arrived on the White House lawn that was derived from all these meetings. | ||||

| [0:45:54] | Prouty: Yes. And people have to understand, when you would talk about the Joint Chiefs of Staff, there’s an organization called the Joint Staff. Now, in my day, by law, it could not exceed 400 people. And so I was one of 400 and people say, "Well, what’s your job?" Our job is to do this kind of thing. When General Krulak would come back, he’d throw notes on the table before five or six of us, or even tape record, cassette recording, and he’d say, "There’s what we did today. Now look, each one of you do such and such a part you’ve been working on, and we’ll get this report the way the President wants it. " | ||||

| [0:46:34] | And when it was the way the President wanted it, that’s when it went out to Hawaii to Taylor and McNamara, so that when it came back, the President was ready to sign it as his policy for Vietnam, which was he was not going to put American troops into Vietnam where we put—do you know how many troops were really in Vietnam? 2,600,000 and 58,000 were killed, let alone all the other people that were killed. | ||||

| [0:47:02] | Ratcliffe: By the time it was all done? | ||||

| [0:47:03] | Prouty: By the time the Vietnam War was over, 2,600,000 men had been rotated through Vietnam. We don’t really often think about that. We’d dropped more bombs from aircraft in Vietnam, in Indochina, than all of World War II. People don’t have any idea what Vietnam really got to be after the death of Kennedy. Well, in all of those big numbers that I’m talking about, the money that rolled out went at least to $570 billion. | ||||

| [0:47:42] | Now, if Kennedy had not died, he would not have put those people there, not just the 500,000 that were there at any one given day, but the 2,600,000. And if the people didn’t go, they would not have had to spend the $570 billion. Well, as General Eisenhower said in his great speech, which was the opening of the Stone film: that beware of the military industrial complex. And when you threaten such a complex with the potential of 570 billion, and then you’re going to bring it down to nothing, you are bound to get some hotheaded decisions, and the removal of the president is not a very difficult thing to do. Just think of the list of presidents who’ve been wounded, shot at, killed since World War II. A lot of people don’t know that even President Carter was threatened with assassination, and President Reagan had a bullet in him. It’s a very, very different world when we don’t use things in a factual basis and really know what’s going on, because then the public is so badly confused, plus in debt, confused, and deeply in debt. | ||||

| [0:49:17] | My book is here. In the book, I could show you just to make a point, I knew the document. I inserted it in this book of mine, the picture of these men coming back to Washington with this report. It’s on the coffee table in the President’s office. | ||||

| And if anybody thinks that that huge report could have been written while they were running from one place to another in Vietnam—you see that big report on the coffee table in front of the President, and Maxwell Taylor and McNamara there, that is the report of the trip. They couldn’t have done that on the back of envelopes while they were running. And it was very carefully designed by Kennedy to support his Vietnam policy, you see. | |||||

| [0:50:15] | It’s like saying he was to blame for not providing air cover for the Cubans. Here’s something people are saying, He had no polished review. The thing that’s very interesting about Kennedy’s death and this work. There was a meeting convened in Honolulu on the 20th of November 1963. A very strange meeting because 60 leaders of our government, including the ambassador from Saigon, among others, and all of Kennedy’s cabinet had gone to Honolulu, and they had this meeting about what to do in the future with the Vietnam War. Despite the fact that this existed, there was this meeting about the Vietnam War. | ||||

| [0:51:05] | The interesting thing is that the report that they released that day, November 20th, and published in the New York Times, among other papers, on the 21st, is a glowing report of how things were becoming better in Vietnam. And yet, on the same day, November 21st, 1963, a [draft] report was written called NSAM 273, which was reversing some of the Kennedy policy for Vietnam. And yet, hypothetically, this NSAM—new NSAM—would have to be signed by Kennedy, and yet the Honolulu meeting was providing Kennedy with assurances that everything was going well. So could it be that this NSAM 273 was somehow signaling a change, which of course, by March of 1973, when NSAM 288 came out under Lyndon Johnson, escalated the war to what we saw later. | ||||

| [0:52:19] | Ratcliffe: Now you said March of ’83. You mean March of ’64? | ||||

| [0:52:22] | Prouty: ’63—No, March of ’64. | ||||

| [0:52:23] | Ratcliffe: March of 64? | ||||

| [0:52:24] | Prouty: Yes. Thank you very much. March of ’64, but you can see the changes in it. And some of these people have said, again, referring to the Kennedy policy of not withdrawing America, but not putting Americans in. Withdrawal was bringing the boys home for Christmas, but the not putting them in. They completely overlook this rapid change that came right about the time the President was killed. And to me, it just underscores terrifically the way history books are worked on. | ||||

| The Pentagon Papers | |||||

| [0:53:07] | In 1967, sort of summing up all of this Vietnam period, Secretary McNamara of the Defense Department ordered a group to write the history of the US in Vietnam from 1945, notice the date he picks, ’45 to the present. And the present would be when they got it done, the end of 1968. So rather in a chronological manner, they wrote what amount to being five volumes this size of this history of the United States, a history written by people in the Pentagon, paid for by the US government and published by the US government. | ||||

| [0:53:55] | It’s called The Pentagon Papers because it is the same stack of highly classified papers that Daniel Ellsberg released to the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post, and a few other papers. And of course, Ellsberg got in serious trouble for violating security and releasing this, which of course was very good advertising for this because this was put together, as it states clearly in the opening paragraphs, by a man named Les Gelb. | ||||

| [0:54:31] | Gelb was working in the Internal Security Agency offices of the office of the Secretary of Defense. That’s where he was working. It also just happens that if you look in the Pentagon telephone books of the period, you find that not only is Mr. Gelb listed in ISA, but Daniel Ellsberg is listed in the Pentagon telephone books. And anybody that has enough interest to want to read history should just look in these books because a lot of other nice names in here. General Richard Secord was working in the same office. Mr. Eagleberger in the State Department was working in the same office. | ||||

| [0:55:20] | Ratcliffe: ISA? | ||||

| [0:55:21] |

Prouty: ISA. Bill Bundy was working—Bill Bundy was the head of it for a while, ISA. So they had little Robin’s Nest there that was bringing out all these things. But something that I want to emphasize on this business of history, because most history professors, and therefore, unfortunately, most history students, believe that The Pentagon Papers are the essence of the Vietnam War, period, and that if they study these, they know what went on.

The book is written in chronology. Like the page I’m open to here has the 3rd of November, the 4th of November, and over here on this page, 9th of November, the 20th of November, the Honolulu conference, the conference I was talking to you about with all the people out there. The entire country team met with Rusk, McNamara, Taylor, Bundy, Bell. So I have a letter, copy of a letter Bundy wrote in 1991, this is McGeorge Bundy, saying he wasn’t there. He was listed. Maybe the history book’s wrong. |

||||

| [0:56:22] |

But it’s real interesting, they write up to the 20th. Then on the 22nd of November 1963, on a blank slate in the Pentagon, they wrote this:

|

||||

| [0:57:08] | But what’s missing? The men that wrote this wrote it in 1968. They hadn’t heard that Kennedy had died. They didn’t even know Kennedy was missing. When Lodge confers with the President, they didn’t clarify whether he met with Kennedy or Johnson or neither. This is how history is written today, you see? And such things as that are very powerful in the minds of people in college today who are too young to know the things that I can remember about General Walter Bedell Smith or General Ridgway or General Bradley or Allen Dulles. I’ve worked in Allen Dulles’ home with him. I know what Allen Dulles thinks about various things. I’ve worked with him in John Foster Dulles’ home. | ||||

| [0:57:56] | Well, why can’t we tell it the way it is? Why can’t we tell it truthfully? So on the 22nd of November, according to this five volume study done by 36 PhDs working with Les Gelb, who has been the managing editor of the New York Times, among other things, on the 22nd of November, they didn’t even notice that the President of the United States had been shot. And the rest of our history books are just about that good. It’s terrible. It’s a disaster. | ||||

| [0:58:30] | Ratcliffe: Now, this is very significant with this edition of The Pentagon Papers. You said this is the Gravel Edition, which is the one you feel is the best of the ones, the one that Gelb helped put out, which was the New York Times edition that was just one paperback. | ||||

| [0:58:44] | Prouty: Yes. There’s a great distinction between that and your point is very well-made. You see, there was much—when these papers were released, the idea was that this young man, Daniel Ellsberg, had released, I think, over 4,000 top secret documents. And that’s all he talked about, the top secret documents. You don’t do that. President Nixon went right through the roof. Well, Senator Gravel could see in this some very important historical records. So he took the complete set of documents and he sat there in the Senate and for days read every single word. That’s why this is called the Gravel Edition. That put all of these documents into the Congressional Record officially. If you wanted to go back and buy a Congressional Record of that period and get a great big truck to haul it away, that’s what this is. So the Gravel Edition is a fundament to understanding this period because point by point, this is what the Pentagon papers were. Now that’s all that guarantees. | ||||

| [0:59:59] |

There were no way Senator Gravel could get into this thing. The fact that Senator Gravel, by the way, was born in Massachusetts, he knew who Kennedy was. He’d have put Kennedy in here as having died that day. But he was a Senator from Alaska, but at least he knew what was going on. It’s quite a commentary on the way history is treated. And again, like with the GSA book, this book of The Foreign Relations of the United States is about the period August to December 1963. The book is released and printed in 1991. You see, from ’63 to ’91, you can have what, four or five generations of college students, high school students. You can have many, many, many history books written, people who can write anything they want because they don’t have sources, so they just use their imagination, write anything they want. And finally, about 30 years later, you get the official record.

And you know what? And I do this many times. I go to campuses to lecture and they say, "Well, we hear what you say, but we read six books in our class and this is the way it was." That’s poison. That’s poison. But it’s the facts of life because you can’t get the record. They do it backwards. The government should release the record immediately. It’s not secret. My God, there’s nothing about the Bay of Pigs that was secret 10 minutes after the guys landed. In fact, before they landed. What’s secret? This here was not only—there’s a special stamp on here. This paper was not only stamped Top Secret, it was stamped Ultra Sensitive above Top Secret. But what was ultra sensitive about the Bay of Pigs after—and let’s look at something else. Important people are involved in these things. You’ve heard the name, haven’t you? |

||||

| [1:01:53] | Ratcliffe: Sure. | ||||

| General Lansdale, the JFK Assassination, and the Cover Story | |||||

| [1:01:54] | Prouty: General Lansdale. Now, I met General Lansdale in the Philippines in 1953. I was a commander of a military air transport squadron. And my regular duties, just like an airline, were flying from Tokyo to Manila, to Saigon, to Bangkok, and on through to Dharan and Arabia, through India. And on the other side, fly to Honolulu. So we had an awful lot of ground to cover. But in my going back and forth through Manila, I met Lansdale. I met Valeriano, his Filipino friend who was Magsaysay’s chief of staff and people like that. So I know Lansdale very well. Later when Lansdale came back from the Philippines and when I was done, we both happened to be assigned to the Office of Air Force Plans. And his office was just one section over from where my office was. I knew him very well during that period. | ||||

| [1:02:48] | Then in early 1960, General Lansdale was assigned to the Office of the Secretary of Defense in the Office of Special Operations, which covered clandestine operations, the national security agents, the reconnaissance business, all the highly classified jobs. And within a month or so, I was transferred to the same office to do the same work in the Secretary of Defense’s office that I’d been doing for the Air Force, which was the military support of the clandestine operations of CIA. So then I was responsible for a global program. But again, we were both back in the proximity of each other. So I would say I probably knew General Lansdale as well as anybody. I wouldn’t make it a broad claim, but I know enough to know that when I read a biography about him or when I read his autobiography, that strangely enough, like they did in The Pentagon Papers not putting Kennedy’s assassination in there, there’s a lot of things in here that are wrong because having lived in this covert, clandestine atmosphere for so long, there were just many things he can’t write, so they’re not in the book. | ||||

| [1:04:09] | And for instance, one of them here, his biographer writes about me because I wrote in my books what happened, and I wrote that General Lansdale was a CIA man operating under the cover of the Air Force. And the biographer says, Prouty’s all screwed up. He doesn’t know that. I’ll just tell you a little incident about that to show you how I know among other things that happened. I was promoted to Colonel in 1960. And when I came into the office, Lansdale came over and congratulated me. And then we sat down and we were having a cup of coffee together and he said, "You know my position." He said, "I’m much older than you are. I’m much older than most Air Force colonels. I’ve been with the CIA all my life. How do I get a promotion?" I said, "You want a promotion to general?" He said, "Well, it would be more fitting for the work I’m doing." "Okay, [I’ll] take care of it." | ||||

| [1:05:10] | So I went back to my office, I wrote a note, sent it over to Allen Dulles and I told him, I said, This man, Lansdale has been a colonel long enough for Air Force Service. The Air Force would be promoting him and since you pay his salary anyway, I’m sure the Air Force will not have any problem with it. Simple note, and Allen Dulles and I knew each other very well. He knew Lansdale very well. And about two weeks, three weeks later, I got a call from the office of General Curtis LeMay, Chief of Staff of the Air Force. I had worked with General LeMay many, many times. So I went up to the office to see what it was and he had a sheet of paper in his hand and he said, "Prouty, this is the list of men we are promoting to Brigadier General, but there’s one name on here I don’t know, but they tell me you know something about it. What’s the story?" | ||||

| [1:06:02] | So he showed me the list and here’s General Lansdale’s name to promote to Brigadier General by the Air Force. I said, "Oh, don’t worry about that General. Allen Dulles is paying his salary. He’s a CIA man. This is simply a cover assignment. You’re going to let him wear stars on his shoulders, Air Force uniform. He’d been in the Air Force uniform all through his career, or at least since the late 40s, and they’re going to promote him to general and the pay will come from CIA. Don’t worry about it." "Fine." He signed the paper and put it in his out basket, General Lansdale. So I went downstairs and I said, "Ed, you’re a general." "How do you know?" I said, "You wait, you’ll get a call. You’re a general." Well, was he CIA or was he Air Force? Now, do you want me to understand and believe his biographer or the facts of life as both Lansdale and I led them? | ||||

| [1:06:53] | And this leads me to an extremely key point in the Kennedy assassination because you see the fact that when I look at his biography and see that it isn’t correct, I can see other things that come through that involve Lansdale that are not understood and some of them are rather fundamental, some are quite important. Not long after the Warren Commission had come out, a friend of mine showed me a group of photographs that had been taken within the period of 30 minutes before the time the President was killed and 30 minutes afterwards, thinking that people who were involved, they’re bound to be or may be within that group. And among them were pictures which had become quite famous among the assassination buff crowd, that people are studying this thing seriously. And that group is called The Tramps. I think there’s seven or eight pictures, there may be more. I think I have about eight of them. So here it was, what, late ’64 when the Warren Commission came out about that fall. | ||||

| [1:08:06] | Ratcliffe: Fall of ’64. | ||||

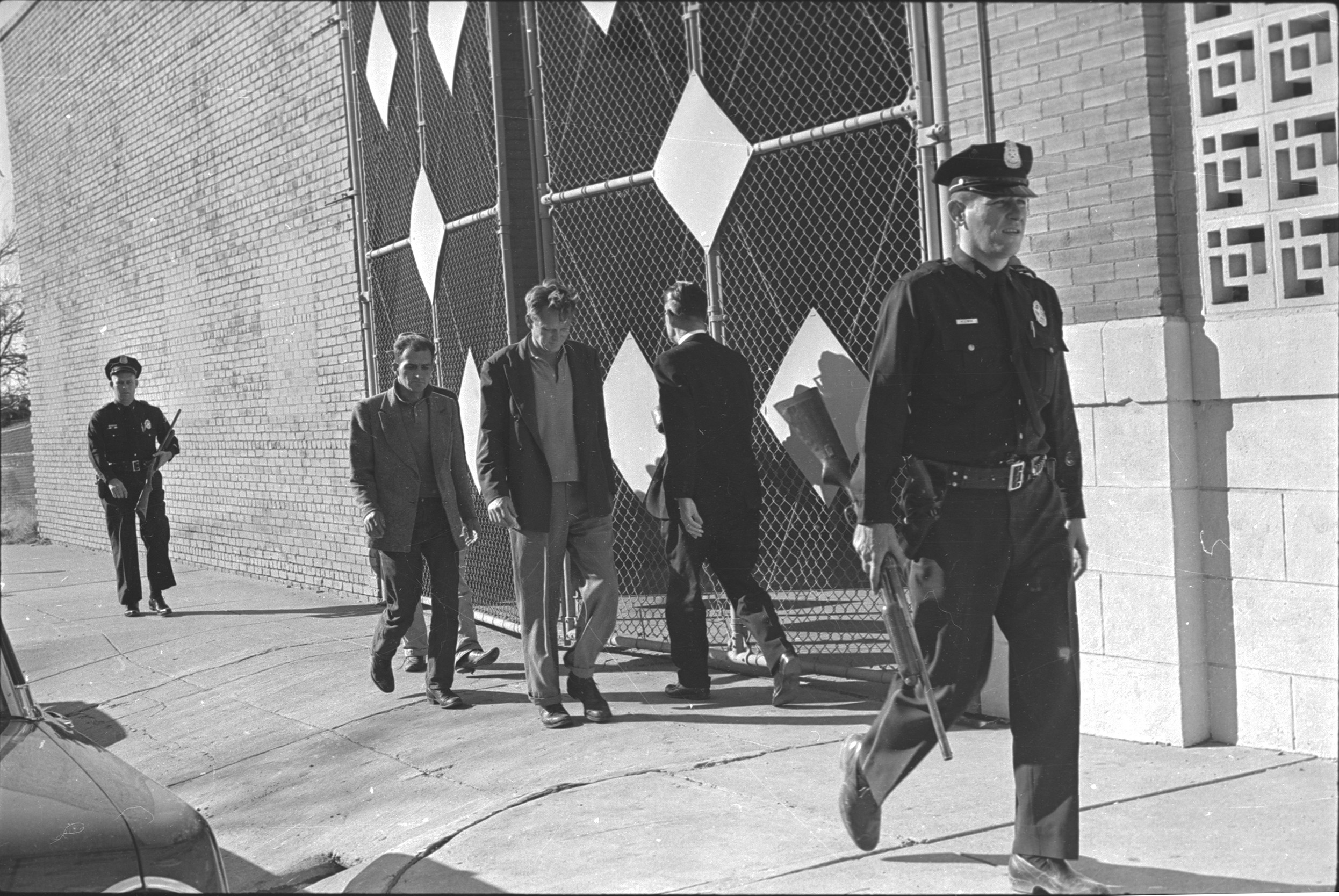

| [1:08:07] | Prouty: And I was shown this photograph among others. And it is chronologically the first picture of The Tramps. The police, the men here, the two police, were leading these four men. | ||||

| [1:08:23] | Ratcliffe: Three men. One of them sort of obscured and then— | ||||

| [1:08:27] | Prouty: Excuse me. I’m counting on one man that’s extra. Three men. Were leading them from the freight car where they had removed them from the freight car and were taking them to the Dallas Sheriff’s Office to register them. And as they were walking from the area of the railroad yard— | ||||

|

|||||

| [1:08:43] | Ratcliffe: Stockyards. | ||||

| [1:08:45] | Prouty: They began to come by the School Book Depository building where allegedly Oswald had fired the shots. So they were just coming by the corner of the building and this is the garage door fence material that’s there. Well, I didn’t see that picture for more than about 30 seconds. Then I realized that something very strange is in this picture. Here’s a policeman, here are two tramps, one of them sort of behind the other, so you don’t see it clearly, but if you look at the feet, you can see there are four feet down there. Here’s another tramp, and here’s another policeman. And here’s a bystander, casually walking by this strange little scene of two policemen with shotguns and three prisoners, presumably. The policemen hadn’t bothered to put handcuffs on them. If they thought they shot the President, they least they could do is put some handcuffs on them, but they didn’t bother to do that. | ||||

| [1:09:42] |

And here’s this stranger going by. Doesn’t even look at them. Just wandering down the street as though he was going to get a cup of coffee somewhere and this happened every day. That, I realized immediately is Ed Lansdale. Now, I don’t know why he was there. I was in Antarctica myself. I don’t have any idea what he was doing in this. But I did know that at the end of October, he had resigned from the Air Force. So he was not on duty and he had told his friends that he was going to visit someone, I think his son, in Phoenix, Arizona. And so during this same period in November, he was on his way to Arizona driving. And we found later through the facilities of the movie group with Oliver Stone, and from the records, Lansdale’s records that are at Stanford University in a box of just random things, there is a hotel bill that was paid by Lansdale in the Fort Worth Hotel in Fort Worth, Texas within the week when Kennedy stayed and Johnson stayed in the same hotel on their way to Dallas on November 22nd.

Now, why Lansdale happened to be in the hotel at that same time? We have been unable to get further records from the hotel. It has changed hands several times since then, and they’re not there. But I had no question about the identity. And to confirm my own feelings, I have gone to the trouble of writing a letter to some people who know Lansdale as well as I do. And the way I put it was, "This is an interesting picture of the police and The Tramps, and we’ve been trying to identify The Tramps. Could it be that in your CIA activities you ever saw these tramps or even the police, they appear to be in costumes instead of real police." Just I avoided mention anything about the guy going the other direction. I just said, "Can you identify anybody in this picture?" Every answer said immediately, "Didn’t you notice that that’s Lansdale in a picture?" See? |

||||

| [1:12:03] | So it begins to open a door to an area of information about the assassination of Kennedy that a lot of people haven’t thought about, haven’t known about. But he was an expert at things that are more important than shooting in a thing like the assassination. Any conspiracy of that order must have a cover story that lasts year after year and is impregnable, because if you’re going to kill the president, you’re going to be in power. Nobody can prosecute you. Nobody ever walked up to any of these people, even though they’re in the pictures and everything else and prosecuted any of them because the people that killed the President control the authority of prosecution. | ||||

| [1:12:49] | So as you study what happened, someone had to orchestrate the cover story, the Lee Harvey Oswald cover story, the Ruby cover story, and the New Orleans side of it. All that sort of stuff that the people have studied so meticulously since then has all been orchestrated just like somebody writing a movie or a play. Just like Shakespeare working and putting all the characters and then making it live for 30 years. That cover story—there isn’t a newspaper in this country that will print the simple sentence, "Oswald did not do it." Not one, but 90% of Americans believe he didn’t do it, at least not alone. He was in with a group. Lyndon Johnson told Leo Janos when he wrote for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in July of 1973. Whoops. | ||||

| [1:13:53] | Ratcliffe: That’s all right. We can pick that up. | ||||

| [1:13:58] | Prouty: Yeah. Hello? | ||||

| [1:13:58] | Caller: Hello. Good afternoon. I’d like to speak to Colonel Prouty. | ||||

| [1:14:03] | Prouty: Speaking. | ||||

| [1:14:09] | Caller: Colonel, My name is [inaudible], I’m calling from New York State ... | ||||

| [1:14:12] | Ratcliffe: Verification of the identity of Lansdale from so many people in this photograph, what is your sense of what he was doing there? | ||||

| [1:14:20] | Prouty: I think it’s pretty clear that his role, because he was so good at this, was the person who orchestrated the cover story. Now, many people don’t think about how conspiracies work. It’s not natural to us. It’s simple to shoot somebody, especially with experts, and this government has trained experts, but to create a story that travels through the years and includes people like Oswald, Ruby, the New Orleans scene, all the rest of it, all these things that people have found out, everything that’s in the Warren Commission report that of course is false, is a cover story. And somebody has to write that script and somebody has to set up those individuals and also give them the assurance that "Look, fellows, we’re on the winning side. No one’s ever going to pick you up. The police ever pick you up, it’ll be because I told them to, because you broke the rule, but don’t break the rules, you’re not going to be in any trouble." | ||||

| [1:15:17] | It’s a tough game, but he does it. Well, I don’t know anybody that was better at that kind of script writing than Lansdale. He had the experience from the Philippines, he had the experience from many other things. He was an expert at that. And I fully believe that the cover story and that part of the scene was a function of Lansdale and his associates, the other people working with him. And as you look through the way this thing happened, you have to respect the fact that there were a lot of people who knew before Kennedy was shot that this event was going to happen. | ||||

| [1:15:57] |

For instance, I myself was sent to Antarctica, a rather strange thing to have happened to me when I’d been nine years in the Pentagon working on the same job and all of a sudden some one of my superiors decides I have to go to Antarctica on military orders. Of course, it even started in a more inferential way as the person who told me about it first was Lansdale. I met him in the hall one day and he said, "Prouty, come on and let’s talk about something for a minute." Went in his office and he said, "I’ve been talking with the people who are running the next operation to Antarctica and they would like to have you go to Antarctica." Well, I knew what he was doing. He’s being a general. I’m listening to my superior officer and he already told me that he had discussed it with the people in the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was working with Secretary of Defense at the time.

And the next step was for me to go to the Antarctica office over at the White House. I went there, my name was on the records. I was on the list. I was on orders to go to Antarctica at this period of time, which didn’t mean anything special to me. I’ve made trips all over the world anyway in this job I was in. So that’s where I was when I was on my way back from Antarctica. I was in New Zealand at the time, I heard about the President being shot. I was with a congressman, we were having breakfast. It was 7:30 in the morning. We were having breakfast in New Zealand, and it was the 23rd of November in New Zealand, of course, on the other side of the date line. And it was 12: 30 when Kennedy was shot. |

||||

| [1:17:32] |

|

||||

| [1:18:37] | And then you know the timing of the motorcade. You know when they’re going to be at Dealey Plaza. You have a man out in the open who just does what we’re doing in the picture, looks up at the building. If a window’s up, he gets on his radio instantly—there are gunmen on the roof across the street—there are people in the building— and says, Hey, go and get that window down. Most of the time it’s innocent. Some secretary raises a window, she wants to see what’s going on. But you control the building. That was not done and is clear in the photograph. So I had a little bit of doubt when I first saw the paper that things were being done different. I had worked in this kind of work. I had gone to Mexico City, when President Eisenhower was president, working on his protection in Mexico City. With all the millions of people around, we had to be very careful what street we took him down and how we covered the streets. | ||||

| [1:19:28] | So I’m familiar with the work. I don’t do the work. It wasn’t my job. I’m familiar with it. I’ve been sent on such jobs. Another thing I noticed that I haven’t read in later information was that reporters right on the spot had sent out in worldwide news this information, and this is in bold type in the paper, "Three bursts of gunfire, apparently from automatic weapons were heard. Secret servicemen immediately unslung their automatic weapons and pistols." Now that’s printed in this newspaper under the worldwide press, NZPA and AAP, Associated Press around the world. Furthermore, if by any chance you happen to be listening to CBS that afternoon about the President’s visit to Dallas, CBS interrupted their programs and read the same thing. "Three bursts of automatic weapon fire." Now, have you ever heard anybody, including the Warren Commission, say that there were three bursts of automatic weapon fire? | ||||

| [1:20:37] | Have you ever seen a picture of what went on in Dallas at that time with the Secret Servicemen unslinging their automatic weapons and their pistols? They didn’t make a move. The only Secret Service there were the ones on the car, behind the President’s car. And if you remember the famous pictures of that, they didn’t even move. They’re hanging on the car. So where did that news come from? Or since this probably came from a reporter standing on the ground who was simply reporting what he saw, it is probably the truth. And what we’ve been hearing later is not the truth. We have a choice, but it’s printed here. It was broadcast by CBS. It must have happened. Why don’t we know about that? That’s part, again, of the cover story game and becomes so evident when you go back to something like this with nothing but a source document. | ||||

| [1:21:29] |

|

||||

| [1:22:22] | And if you remember, the pictures of him taken after he was arrested in the theater, he had on a t-shirt, I think, or polo shirt, that’s all. But here he is in a business suit. Now, where did all that stuff get put together and prepared into a story that you could read on and on, onto the back pages about Oswald when he hadn’t even been charged with the murder? He’d been charged, he was picked up on suspicion of the murder of the Policeman, Tippit, but not the President. So we go back again to this photograph and, you see, somebody has to write the script first and this Oswald script was already written. Oswald was already, what he said in his own terms, the Patsy. You see how it fits together? And then you get the whole scene. | ||||

| [1:23:15] | Ratcliffe: Now, Lansdale worked in the government. He was connected with covert operations. The only other question initially that of course occurs is, well, Gosh, he must have not liked Kennedy, or he must have been with people who didn’t like what Kennedy was continuing to try to effect or do because he was working with people to take out this President by totally illegal means, and he’s in effect connected with members of government groups. Did you ever have any sense of him personally, of his own personal feelings about that you could say plausibly, "Yeah, he was connected with the conspirators." | ||||

| [1:23:59] | Prouty: Well, there’s two things. Your question is very basic and there’s two things that that refers to. First of all, there were times when he was very upset by Kennedy. Just after Kennedy’s election, Lansdale left the Pentagon on a quick trip to Saigon to see his close friend Diem. | ||||

| [1:24:23] | Ratcliffe: Who he had helped make be the father of his country. | ||||

| [1:24:27] | Prouty: Yes, in fact, I’m glad you bring in that because before he left, he came to me and he said, "I’m going to Saigon. I’m going to see Diem. Would you run downtown and buy me some souvenir to give to President Diem? Get me something, some big gaudy thing to put on his desk." So I went down and I found a huge, it looked to me like mahogany base with a place for a clock and your fountain pen and a calendar all built into it, really great and some big emblem in the middle of it. I took it back and showed it to Lansdale. He said, "It’s great, but on this," like a shield that was brass, he said, "I want you to carve on, have somebody engrave on there, The Father of His Country, Ngo Dinh Diem." So I took it back and they did it. | ||||

| [1:25:21] | He carried it to Saigon and gave it to Diem. And I’ve always remembered it because it cost me $780. It took me a long time to get that back, but I got it back. But that was his trip as he went out there, see. When he came back, it was January of ’61 and Kennedy had been elected and Kennedy was going to be inaugurated. And I think it was pre-inauguration, but it might have been just afterwards, either way, he left our office one day for an invitation to the White House and he briefed President Kennedy about his trip to Vietnam. | ||||

| [1:26:02] |

And it was the first close in, up-to-date briefing Kennedy had after he’d been elected and with all the things he’d been through in the year ahead with his run for the primaries and everything else, it got him up to date on Vietnam. And as Lansdale went out of the room, Kennedy turned to some of his advisors and said, "You know, that man would make a good ambassador to Saigon." And Lansdale heard that and he came back to our offices and one or two of us were together when he walked in and after telling us about how successful his meeting with Kennedy was and how highly he regarded Kennedy, he said, "And I may be packing to go to Saigon." And that was his ambition to go back as ambassador. He thought that would be the peak event in his life. Well, it would be.

As the months went on up to about April, after the Bay of Pigs and Kennedy began to sour on the agency, and probably in the interim found out that Lansdale was a CIA man, not a military man, which would change his whole view of him, you see. Kennedy, without saying anything to Lansdale, appointed another man to be ambassador to Saigon. Well, I know personally from my morning coffee with him and from other things that it hurt him very badly. |

||||

| [1:27:26] |

So sure, he had a reason, but I’d like to emphasize something else that I think a lot of people just don’t think about. When you’re thinking about the CIA, an important letter in the CIA is the word A. It’s an agency. And an agency like a lawyer, works for its patron, works for somebody. And furthermore, Lansdale in many respects was the epitome of a CIA agent. And they’re all talking, You’re an agent. Which means he’s on orders from somebody. From his family background and other things during his lifetime, he was close to people in big business. When he went to Manila, he was not against Quirino, but he had been told to overthrow Quirino lawfully and get somebody else into President of Philippines. It wasn’t because he didn’t like Quirino, it’s just his job, he was an agent. And he did it very successfully. It was very successful, quiet and effective. And he got Magsaysay elected legally, but the votes were there to count. And Quirino was out, that was a job.

So, if he had this job of working up the cover story, not killing the President, working up the cover story, which of course is hand and glove, it’s, I think, in the role of agent. He was a perfectionist, no one else could have done it as well. And I think that that should be respected. That’s why when I write about him, that’s always been a plus. I have never accused him of the idea to kill the President. I think he was given a job to do. I’ve known other agents who were given equally difficult jobs and carry them out. It’s their business. So I think we have to be very careful about the understanding of events like this, even though we are thoroughly opposed to it. I mean, if I’d have known somebody had given him a job, I’d have tried like mad to talk him out of it. But that’s another story. But you see, that’s what I think his role was. |

||||

| [1:29:40] | Ratcliffe: Why do you think he then—what purpose would actually be served by him being in Dallas if it was more the thing of scripting the cover story that would be floated out internationally? | ||||

| [1:29:52] | Prouty: Oh, it’s just like when you’re making a movie, the director is right up front. And when the actor or actress do something great and they just step off the film at a moment, they pat him on the shoulder, doing fine. If you notice in this picture, these men have a little smirk on their face. And I mean, my God, if you had just shot the President and had been picked up by police, you wouldn’t smile at some little thing. I think that as just the fact that he walked by and they knew who he was, they thought this is assurance. We were doing our job right, don’t worry about things. And to carry that forward, as you go through—I have eight of these pictures of the chronology of their walk across Dealey Plaza, the last one ends on the steps of the sheriff’s office. | ||||

| [1:30:43] | Policemen never go to the sheriff’s office. These weren’t policemen. They’re actors. Their uniforms are different. They have some sort of a hearing aid in their ear, so on. But anyway, it’s all a scene. When they went into the sheriff’s office where the newspaper reporters were told that they were booked, there’s no evidence at all that they were ever booked and they were never seen again. So you see, they have the right to smile. Lansdale gave them assurances, everything’s all right. And I think he may have circulated among the people who were there. And if the more you look in the pictures at that time, the more you begin to recognize people that were there. It was just to make sure that they all knew things were going all right. They had no way to lose. They won. They had taken over the government. I mean, their bosses have, not them. | ||||