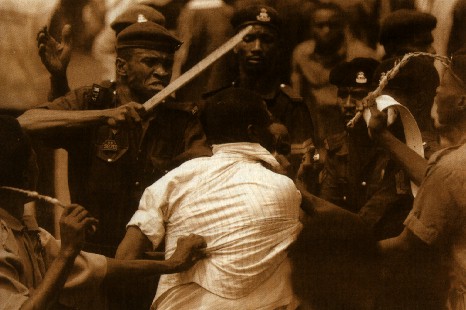

Nigerian police beat arrestee in Lagos

( ASCII text )

The following is reproduced from the fall 2000 edition of Amnesty International's newsletter, amnesty now, pp.4-7.

|

For Nigerian activist Sowore Omoyele,

democracy is worth the risk

By RON LAJOIE

amnesty now Fall 2000

AP/WIDE WORLD

Nigerian police beat arrestee in Lagos |

Before going to a demonstration, Sowore Omoyele always makes sure he has adequate provisions with him. He wears two pairs of pants and stashes an extra tube of toothpaste in one pocket, a bar of soap in another. A battle-scarred veteran of Nigeria's pro-democracy struggle and one of the country's most vociferous student activists, Sowore, now 29, has been detained eight times. Hard experience has taught him that these sundries and a change of clothes will come in handy."My first and second time in jail were pretty difficult," says Sowore, a quietly affable young man with a full round face, a ready smile and almond eyes that only occasionally hint at the intensity beneath.

"You never know when you will get out, and you don't know what the state can do to you," he adds almost casually. "But after those first two experiences, I just accepted it as a normal thing that goes with my work. Being an activist in Nigeria, I train myself to accept whatever comes, detention, even torture, as part of the business."

Currently in the United States to undergo treatment for the torture he endured in detention, Sowore is using his time here to speak for Amnesty International on behalf of other torture survivors and to inform Americans about the struggle for democracy and justice in his homeland.

"The media don't talk to people like me, so you can't blame those who don't have information," he asserts. "Quite honestly, I think the situation in Africa is grossly underreported in the U.S.A. But I think all of us who believe in pulling Africa out of the woods have a duty to enlighten people in this part of the world. There are well-intentioned people in the United States who, if they have adequate information, can put pressure on policymakers to encourage democracy in Nigeria."

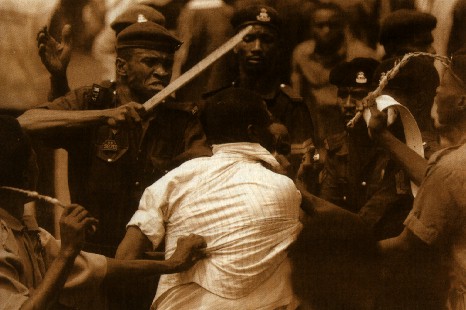

MATTHEW DOYLE

Former student leader and torture survivor Sowore OmoyeleOf oil and democracy

President Clinton traveled to Nigeria in late August, bearing a $10 million aid package to help "bolster," according to the White House, the fledgling democracy there.

In advance of his trip, Amnesty wrote to the President, specifically asking him to reaffirm U.S. diplomatic support for Nigeria's judicial Commission of Inquiry into Human Rights Violations -- and to remind Nigeria's new leaders of their commitment to a civil society.

AI also urged Clinton to ensure that U.S. training of Nigeria's military and police emphasizes respect for the rule of law and human rights. The organization further called on the President to support an independent investigation into the alleged involvement of the U.S.-based oil giant, Chevron, in human rights violations committed by Nigerian security forces.

During a 1998 African tour, Clinton had refused to visit Nigeria, demonstrating his disapproval of the regime of then-military dictator Sani Abacha, though the United States maintained an arms-length relationship with Abacha's government. In June 1998, retired General Olusegun Obasanjo -- a military dictator from 1976 to '79 and a prisoner of conscience from 1995 to '98 -- won the presidency in an election that, though marked by irregularities, was broadly accepted as fair.

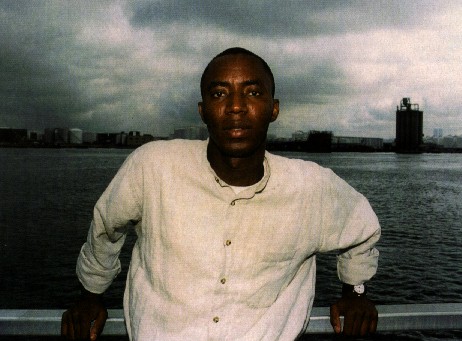

AP/WIDE WORLD

U.S. President Bill Clinton and Nigerian President

Olusegun Obasanjo walk together during their

August 26 meeting in Abuja

But Sowore suggests Clinton's state visit this summer may have been premature. "I would have told him not to go to Nigeria yet," he affirms. "There is a misconception that Nigeria has democratized. But the man who won the election was the military president until 1979. In 1977, he promulgated the Land Use Decree, which robbed the Niger Delta people of their lands. In 1978, he ordered the military to kill student protesters.

"Besides," contends Sowore, "I'm not sure Clinton's visit didn't have something to do with rising gas prices in the United States. I don't know what kind of support he can show a government that's not been able to give any form of dividend to Nigerians, a Senate that is corrupt or an administration that is flatfooted and cannot bring food to the table."

Just weeks before the Clinton trip, Nigerian Senate President Chuba Okadigbo had been forced to resign after an investigation uncovered evidence of widespread corruption. That scandal erupted as social unrest continued to roil northern Nigeria, where jurisdictions in the largely Muslim region moved to institute Sharia or religious law, raising fears among the Christian minority.

And in July, a gas pipeline explosion and fire had killed hundreds near Oviri-Court in the oil producing Niger Delta, once again highlighting environmental degradation and security concerns in that impoverished area. The explosion was blamed on local poachers attempting to siphon off, literally, a small share of the huge profits generated by the multinational oil conglomerates that dominate the Delta.

"We've had supposed democracy for one and a half years and people still can't eat," argues Sowore. "So who has benefited? There's no basic health care. We don't have running water. We don't have electricity, no basic education. Right now, Nigeria is a leaking basket. Shell and Chevron are among the biggest corporations in the world and they have benefited only a few people, the clique that runs the country."

A stubborn foe

Such blunt outspokenness has frequently landed Sowore in trouble with Nigeria's rulers and has cost him his health. But he is willing to accept that risk. His sense of right has deeply personal roots.

As a 10-year-old boy, Sowore watched as a battalion of 300 military police attacked and ransacked his village. During the raid the soldiers arrested his half-brothers and their mother, and raped his 17-year-old cousin.

"I was in front of her and they did this. I saw it happen," he recalls. "That night I silently promised myself that when I grew up I was going to fight back." Nigeria's ruling clique had gained a resourceful and stubborn young foe.

"Well, if stubbornness means standing against the authorities that occupy the political space illegally, I think I can describe myself as a stubborn person," Sowore acknowledges with a smile. "It is just a matter of not allowing the threats, the intimidation, the attempt on my life to stop me from carrying on with what I think is desirable for the good of my people. I am no longer afraid."

The activist's public career began in 1989 when, as a freshman, he joined student demonstrations protesting an International Monetary Fund loan Of $120 million for Nigeria. Though supposedly earmarked for education, the loan nonetheless mandated a reduction in the number of universities in the country from 28 to 5.

AP/WIDE WORLD

Scavengers pan for oil at Adeje, Nigeria, the site of a

July 9 pipeline fire that killed more than 250 people"It was not difficult to differentiate what was wrong and what was right in Nigeria," says Sowore. "It was a matter of taking sides."

In 1992, when students mobilized against the Babangida regime, one of Africa's most notorious kleptocracies, Sowore led a column of 2,000 students in protest. The peaceful demonstrators had marched about two miles when they ran into the police, who immediately opened fire. Seven students were killed outright. The police arrested and severely beat Sowore, herding him and 120 other students into a tiny detention room. Then they tossed in a tear-gas canister. Four hours later, when Sowore had regained consciousness, he was dragged to another room for interrogation.

He later learned that the police had also visited his father's home in Ondo State to intimidate his family -- and that he and 47 other student "ringleaders" had been expelled from school.

The university would subsequently relent and permit the expelled students to return, but only after other students struck the campus to protest the expulsions. Based on the leadership skills Sowore displayed during the protest, he was elected Executive President of the University Students Union.

"That was when I made my mark," he says with almost wistful pride. "The government knew I was a threat."

Tortured in detention

The next year was to prove a time of particular upheaval even for perpetually tormented Nigeria. In June 1993, the military government, now under Babangida's successor and close ally Abacha, nullified national presidential elections and imprisoned the winner and President-elect, Moshood Abiola.

Immediately, the campuses ignited in protest. That July, Sowore led large anti-military rallies through the streets of Lagos. He was again arrested, beaten and warned not to engage in any further agitation. But in November, the impenitent student led another protest. This time the authorities aimed to show they meant business. Sowore was arrested, held incommunicado in solitary confinement for two weeks and tortured.

But worse lay in store. In March 1994, a goon squad of toughs and student informers with links to the police attacked Sowore and 24 other student activists.

Beaten bloody, stabbed in the head, stripped and humiliated, Sowore was injected deep into the buttocks with an unknown substance. At the local hospital where he was taken, the staff was too intimidated to treat him, so he had to be spirited to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. When the police came looking for him there five days later, he managed to escape. Forced to spend the next four months recuperating in hiding, Sowore learned that he had been declared a wanted man and again expelled from the university.

Meanwhile, the police went to work on his known associates, hijacking a student union bus and torturing the occupants in order to discover Sowore's whereabouts. The students wouldn't give their leader up, and when the university reopened in July 1994, Sowore was there to take his final exams. Though the university would withhold his results for six months, eventually he was allowed to graduate.

It wasn't long after Sowore graduated that the Nigerian dictatorship, out of the sort of bureaucratic incompetence that knows no ideology, handed the young agitator his biggest platform. In Nigeria, all students are expected to complete a year of national service upon graduation. Someone, somewhere decided that one of the nation's most famous dissidents would look good on television.

"I don't know who made the mistake but somehow I ended up doing my service on TV," he laughs. "They said, `You are a little bit smart and we have this program we'd love you to handle,' and I said that was fine with me.

"Most of the time I went on the air live. It was like they forgot who I was. The program [entitled Kaleidoscope] was becoming very interesting. I was producing every week for six months when the State Security Agency came looking for me. They said, `What are you doing on TV? You are a security risk, your name is posted at the airport!' But I was very calm. I said it's not as if I broke into the studio. But after that I was not on TV anymore."

In the wake of the official blunder, Sowore was ordered to report to the state security offices once a week.

Deadly serious business

While Sowore was completing his national service, the government executed Nigeria's best known dissident, environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, causing an international outcry. Human rights activism in Nigeria was indeed a deadly serious business.

Six months later, Sowore was approached by men who simply asked him to accompany them to their office. "I knew exactly what it was and I couldn't resist them," he says. Again, he endured six days incommunicado detention shackled to the ground in a tiny cell. Sowore was finally released after a journalist learned of his abduction, but he was not permitted to work.

Instead, he concentrated on student organizing. He also had time to put his broadcast experience to use, co-producing a documentary on Nigeria's oil dictatorship with the U.S.-based Pacifica radio network. He would be arrested again in 1996 and twice in 1998. One day in captivity, Sowore was brought into the office of a military official who told him to stay away from oil issues or, like his hero Ken Saro-Wiwa, he would be killed.

Despite that threat, Sowore traveled to Brussels in January 1999 to attend a conference on alleviating poverty in Nigeria, then to The Hague where he spoke to the Dutch Government about Royal Dutch Shell's activities in his country. The next month, Sowore arrived in the United States to attend a conference sponsored by the Center for Global Peace at American University in Washington, DC. He then checked into the Bellevue-NYU Program for Torture Survivors, located in New York City, to receive treatment for the lasting effects Of the unknown injection he received in 1994.

During his U.S. stay, Sowore has visited at least 20 cities, helping to lay the groundwork for Amnesty's Campaign to Stop Torture,[1] which is set for worldwide launch at press time. This fall, he is working with AIUSA's Human Rights Education Program to help teach students about the reality of torture in the world today.

"Torture is the most potent force in the hands of those who wish to maintain power," he offers. "It allows them to silence dissent. I think I owe the public a duty to talk about my experience because the more we expose them, the weaker they become."

Ultimately, vows Sowore, he will return to Nigeria.

"Change will not come to Nigeria on a platter of gold," he insists. "If you want justice, you have to fight for it."

Footnotes

There are a number of processes one can join.

The following are available from Amnesty International USA:

- Fast Action Stops Torture (FAST) is a new rapid response network dedicated to using the Internet to stop torture. Join FAST and Take Action!.

- Take Action Against the Torture of Children - The dependency and vulnerability of children should render them immune from the atrocities adults inflict on one another, yet violence against children is endemic.

And worldwide, there is Amnesty International's Campaign Against Torture

Manifesto:

Torture is abhorrent. Torture is illegal. Yet Torture is inflicted on men, women and children in well over half the countries of the world. Despite the universal condemnation of torture, it is still used to extract confessions, to interrogate, to punish or to intimidate. In Police stations and prison cells, on city streets and in remote villages, torturers continue to inflict physical agony and mental anguish. Their cruelty kills, or leaves scars on the body and mind that last a lifetime.

The victims of torture are not just the people in the hands of the torturers. Friends, families and the wider community all suffer. Torture even damages and distorts the hopes of future generations.

Amnesty International and other organisations have been campaigning against torture for almost 40 years. Take a Step to Stamp Out Torture and One Click To Stamp Out Torture are boosts to the continuing work against torture. They are global campaigns, launched simultaneously in more than 60 countries. They utilise Amnesty International's experience in gaining media coverage, in publications and in lobbying, as well as mobilising the million individual members Amnesty International has worldwide.

torture - the big picture

In preparation for the campaign, AI conducted a survey of its research files on 195 countries and territories covering the period 1997 to mid-2000. It revealed that AI has received reports of torture and ill-treatment inflicted by state agents in over 150 countries since 1997. In more than 70 torture or ill-treatment by state officials was widespread and in over 80 countries people reportedly died as a result.The world has changed immeasurably since AI first began denouncing torture at the height of the Cold War in the 1960s, but torture continues and is not confined to military dictatorships or authoritarian regimes; torture is inflicted in democratic states too. It is also clear that victims of torture are criminal suspects as well as political prisoners, the disadvantaged as well as the dissident, people targeted because of their identity as well as their beliefs. They are women as well as men, children as well as adults.

AI's survey strongly suggests that common criminals and criminal suspects are the most frequent victims of torture by state agents today. They have reportedly been subjected to torture or ill-treatment in over 130 countries since 1997. Torture and ill-treatment were reportedly used against political prisoners in over 70 countries during the same period, and against non-violent demonstrators in over 60 countries.

AI's campaign looks at torture by police, in the context of criminal investigations or the maintenance of public order; torture and ill-treatment in prisons; judicial punishments amounting to torture; and torture in armed conflict. The campaign also looks at other forms of violence in the home or the community which may constitute torture under international standards, even though they are not committed by state officials.

Methods of Torture

The survey showed that beating is by far the most common method of torture and ill-treatment by state agents today, reported in over 150 countries. People are beaten with fists, sticks, gun-butts, makeshift whips, iron pipes, baseball bats, electric flex. Victims suffer bruises, internal bleeding, broken bones, lost teeth, ruptured organs and some die.Rape and sexual abuse of prisoners is also widespread. Other common methods of torture and ill-treatment include electric shocks (reported in more than 40 countries), suspension of the body (more than 40 countries), beating on the soles of the feet (more than 30 countries), suffocation (more than 30 countries), mock execution or death threat (more than 50 countries) and prolonged solitary confinement (more than 50 countries).

Other methods include submersion in water, stubbing of cigarettes on the body, being tied to the back of a car and being dragged behind it, sleep deprivation and sensory deprivation.

Cruel, inhuman or degrading instruments of restraint cited in AI's report include leg irons and electro-shock stun belts.

Is torture illegal?

The prohibition of torture in international law is absolute. "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment", says Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; similar phrases appear in many other international human rights texts.No government may use a state of war, a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency to justify torture. Under the Geneva Conventions, torture is illegal in both internal and international armed conflicts. Torture and ill-treatment are also illegal under the laws of virtually all countries, although many laws are inadequate.

One form of torture and ill-treatment which is permitted under national law in some countries is judicial corporal punishment. According to AI's survey, judicial corporal punishments are provided by national law in at least 31 countries today.

The most common forms of judicial corporal punishment include amputation and flogging. Some forms such as amputation and branding are deliberately designed to permanently mutilate the human body. However, all of these punishments can cause a range of long-term or permanent injuries.

Since 1997 judicial amputations have been carried out in at least seven countries (Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and Sudan) and judicial floggings in 14 countries.